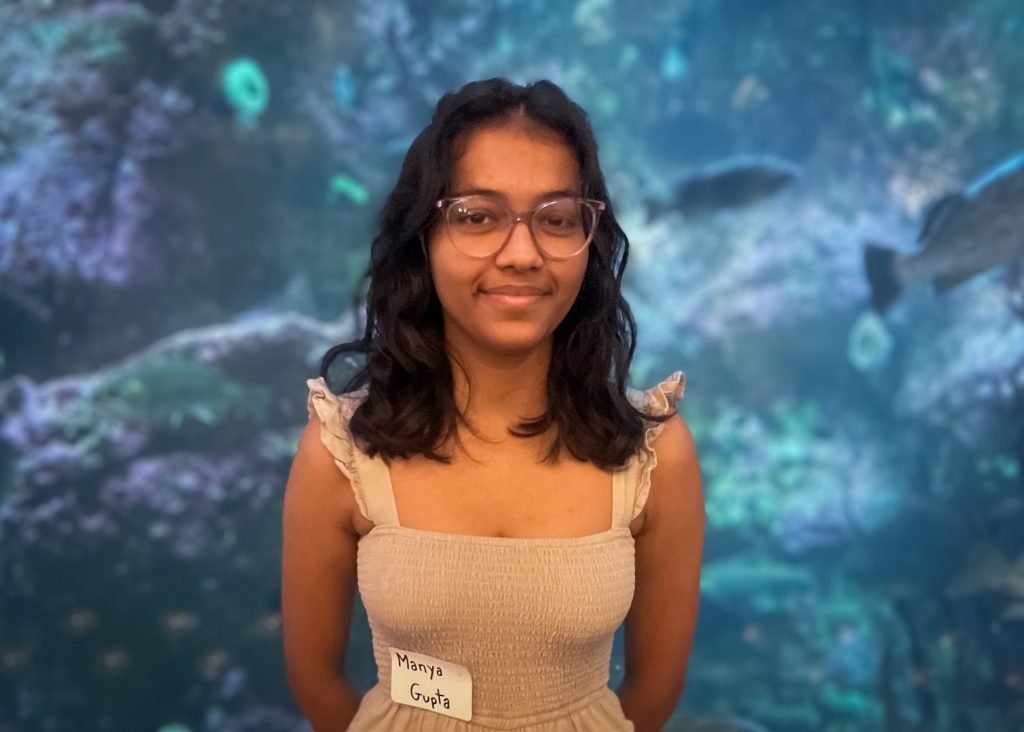

Over her winter break, Manya Gupta walked along Lake Tapps with her cousin looking for deer tracks. Instead, they found litter.

“I haven’t known a life where there hasn’t been plastic on a road or sidewalk or natural habitat,” said Gupta, a senior at Juanita High School in Kirkland. “I’m tired of bringing gloves to local streams and beaches. I’m tired of spending hours picking up bits of plastic produced only to be thrown away.”

Gupta believes the burden of plastic pollution weighs too heavily on everyday people and that responsibility should shift to companies making the packaging. She’s not alone.

On Wednesday, Gupta spoke alongside State Representative Liz Berry (D-Seattle) and State Senator Christine Rolfes (D-Bainbridge Island) who announced their co-sponsored Washington Recycling and Packaging (WRAP) Act. Filed for the upcoming legislative session, House Bill 1131 is a form of an extended producer responsibility bill, which is only in existence in four states. These policies regulate how producers package their products and hold them financially accountable for downstream effects once that packaging is discarded.

In the Puget Sound region, consumers and the recycling systems they rely on have not been able to keep up with influx of plastic and paper packaging, especially since the pandemic started.

Only 17 percent of plastic waste is properly recycled, according to Plastic Free Washington. Even when that waste correctly gets to the sorting centers, it can create problems for machinery that wasn’t designed for packaging like Amazon’s white-and-blue mailer.

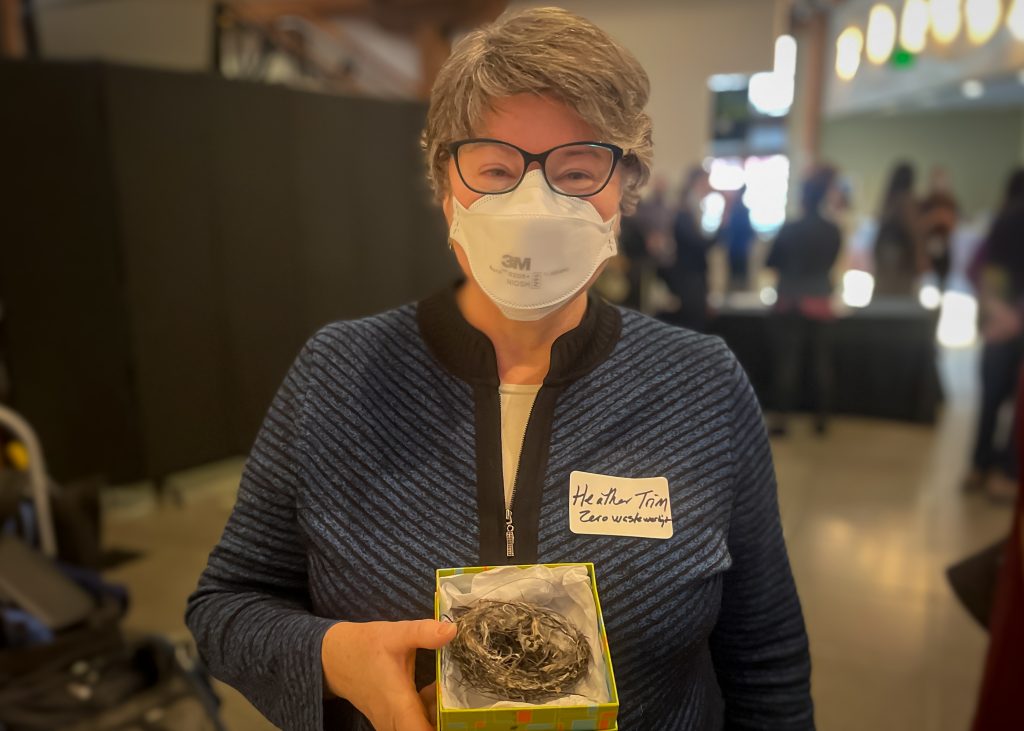

“The recycling facility has all these magnets and robots, and it’s set up to basically sort flat things from round things, basically the newspaper and cardboard from containers like yogurt and coke bottles. The thing about those mailers is they are sorted like a flat even though they are plastic,” said Executive Director of Zero Waste Washington Heather Trim, whose organization supports the WRAP Act.

Trim said that Amazon tried to evolve that plastic packaging into its newer brown paper mailer, which the pulp and paper mills seem to be able to accept, because the puff glue is the same material used in cardboard.

Often, consumer product packaging doesn’t make it to the recycling center at all. Nearly half of the state’s consumer packaging is sent to landfills, because recycling access varies by county and consumers struggle to understand what they can recycle.

The result is nearly $104 million lost in materials that could be reused in the circular economy and more pollution for communities who live near landfills or transfer stations — the King County term for where the public can dump waste for Seattle Public Utilities to sort.

“At landfills, including the one that Seattle sends its garbage to, they have six story high, pitched chain link fences, really tall chain link fences that they erect at the top of a landfill or a silent film, because there’s so much blowing plastic film, and they’re trying to catch it so it doesn’t go off from the landscape,” said Trim.

But that fence isn’t always effective. Seattle sends its trash to Cedar Hills Regional Landfill, which is the neighbor to a state park, school, and homes. Neighboring cities in South King County like Kent, Federal Way, and Renton are some of the most ethnically diverse communities in the United States.

“I hear from constituents often about the importance of recycling,” said Kent City Councilmember Brenda Fincher. “We want to make sure that it’s done correctly, they want to make sure that it’s done anywhere that it needs to be done, that everyone has access to do that. We want to make sure it’s working.”

The WRAP Act seeks to modernize taxpayer-funded waste systems through a framework called Producer Responsibility Organization. Other states, and countries like France, have used these fee-based systems where producers pay to produce materials that are harder to manage when thrown away. For example, if a bottle company had the choice to produce a metal bottle cap versus a plastic bottle cap, they would have to pay a higher fee to package their product with the difficult-to-recycle plastic. The money generated goes into a fund for facility improvements and curbside expansion.

While the WRAP Act establishes a producer responsibility program, it does not take consumers off the hook to recycle. The legislation includes a so-called bottle bill where people must pay a 10 cents fee on beverage containers. At drop-off locations, that fee can be redeemed for cash, put into a college savings account, or donated to nonprofits or schools.

Berry, whose been prioritizing this bill since the 2022 session, said producers still have a stake in the bottle bill.

“We’re going to require them to pay for and set up the systems, millions of dollars of infrastructure that they are going to have to pay for all on their own,” said Berry. “It’s an Oregon-style model, which is considered best in the country, and we weren’t going to include it in the bill, but the more we learned, the more we decided that if we really want to hit reuse and refill targets, you have to have a bottle deposit. So, we threw it in the bill, and we are going to open it up for public hearing and comment and see how it goes.”

State legislators are working to achieve a 2025 goal where all packing sold in Washington will be completely recyclable, reusable, and compostable. Legislators and advocates working toward this goal tried to get a similar bill passed during last year’s session. It failed because negotiations with the business community kept policy language from getting finalized in time.

This round, Berry said they have already been working with companies like Amazon, an example of Seattle-based international businesses already familiar with this system since it is already in effect in other state and countries.

“We worked with hundreds of stakeholders over the summer and fall to get where we are today,” Berry said. “I’m excited to tell my son, he turned me into the plastic warrior that I am today, that Washington will be leading way one step at a time to save our planet.”

This article was corrected at 3pm, 1/6/2022, to reflect that the puff glue in Amazon’s packaging does not disrupt the recycling process.

Ashli Blow

Ashli Blow is a Seattle-based freelance writer who talks with people — in places from urban watersheds to remote wildernesses — about the environment around them. She’s been working in journalism and strategic communications for nearly 10 years and is a graduate student at the University of Washington, studying climate policy.