Restarted by Governors Inslee and Brown in 2019, the IBR has been on a glidepath toward repeating the mistakes of the failed Columbia River Crossing project.

When state lawmakers from both Oregon and Washington met earlier this month to discuss the latest updates on plans to replace Interstate 5 over the Columbia River, the team overseeing the project had just announced that the total cost estimate for the five-mile highway project had gone up by more than $2.5 billion in the upper-end estimate. That new cost projection — an incredibly wide range of $5.5 billion to $7.5 billion — represents an increase of more than 50% over the previous assumptions that had been guiding the megaproject through the selection of a “locally preferred alternative,” which had received the signoff of all local governments earlier this year.

But the panel of legislators didn’t express much alarm at the news, apart from wanting a breakdown of just how much each element of the project (such as the river crossing itself or the interchanges) is now expected to cost. At a separate meeting later that week, Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) Secretary Roger Millar, serving on the project’s executive steering group, was silent when it came to the subject of the new cost assumptions.

If the $7.5 billion cost estimate proves close to accurate, the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) will become the most expensive highway project ever built in the Pacific Northwest by a wide margin, ranking among the highest cost projects in US history, even adjusted for inflation. But it’s not clear that there is any cost amount that would be too high for policymakers to reconsider the core assumptions that lie at the center of the megaproject now decades in the making.

With over $1 billion allocated by Washington State following the passage of the Move Ahead Washington transportation package earlier this year, attention will turn to Oregon in 2023 as the legislature there debates allocating its matching $1 billion contribution, an act that is mostly treated as a foregone conclusion within the highway project team at this point. Oregon may still have some amount of control over what happens going forward, but December’s astronomical cost announcement made one thing clear: Washington is losing control of the IBR. Hitting the brake now is unthinkable.

The Highway Project That Won’t Die

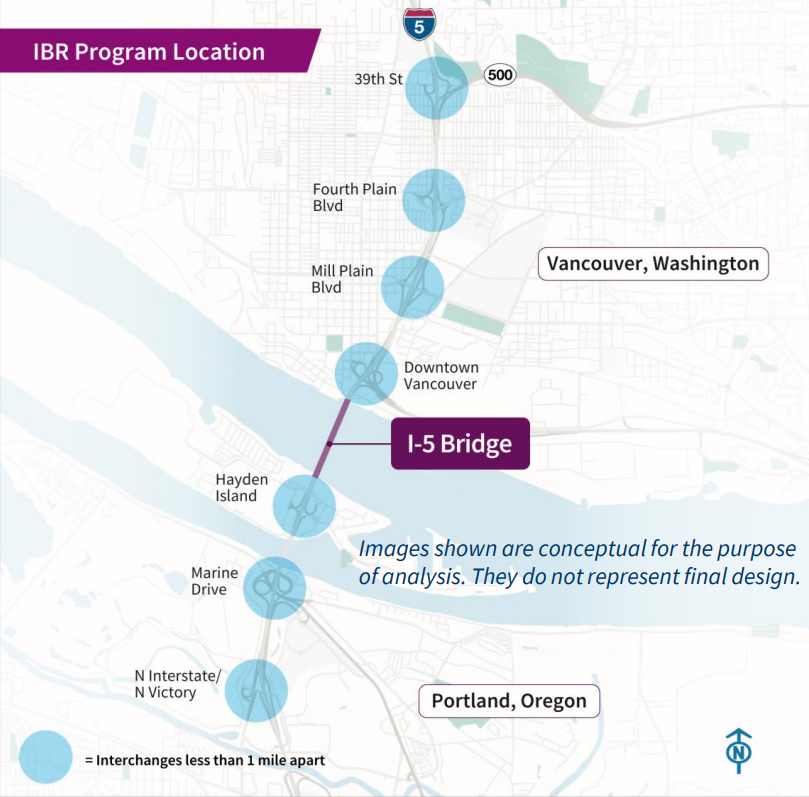

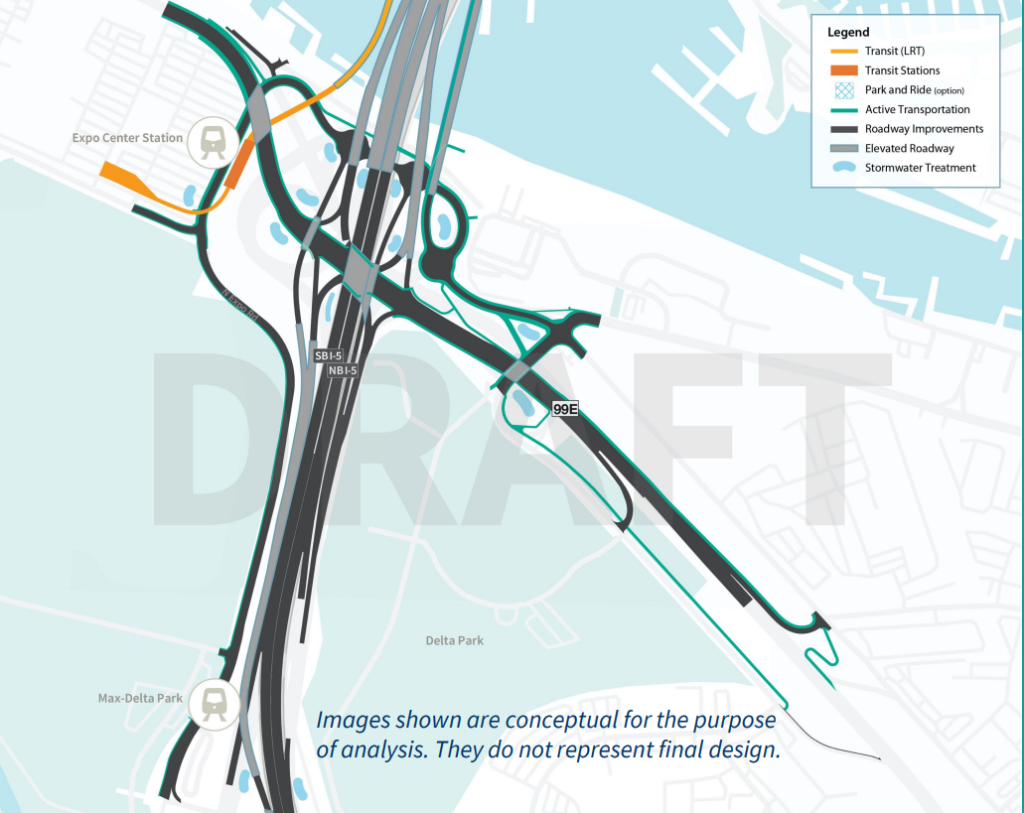

To understand how locked in Washington is, you need to go back over a decade to the previous attempt to replace I-5 between the two states. In 2005, the effort to replace the aging twin bridges over the Columbia River was kicked off jointly by WSDOT and the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT). By 2008, the project had a draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) which for the first time paired a replacement of the highway with an extension of TriMet MAX light rail service into Vancouver, Washington. But along with including transit as a core component, the project defined a Bridge Influence Area (BIA) that included seven existing highway interchanges on either side of the highway. That turned the project into way more than a simple replacement, and thus the inclusion of accommodating “growing travel demand and congestion” was baked into the project’s express purpose.

That DEIS was finalized in 2011 with a Record of Decision, approved by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), setting in stone the project needs at the heart of the project. Even though just a few months later the Columbia River Crossing project office disbanded after the (Republican-controlled) Washington senate declined to provide funding, that Record of Decision is still in place. And it’s that starting point that the current project team is relying on for its accelerated schedule, with 2025 still being eyed for construction — an incredibly fast timeline for a megaproject restarted in 2019.

Despite an impressive communications budget (with $6 million spent on communications already by the end of 2021) helping to revamp the project from the Columbia River Crossing into the Interstate Bridge Replacement, the purpose and need remain recycled from 2011, despite all of the additional understanding of the role that induced demand plays in increasing regional vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and emissions.

In early 2021, the project team announced that it had considered incorporating climate impacts directly into the project purpose and need in the upcoming supplemental EIS process, but it wouldn’t be doing so because it would jeopardize the project’s timeline. Direction from US Department of Transportation (USDOT) officials, amazingly, stated that even if those elements were incorporated, “there is no guarantee that climate and equity would be able to be treated as transportation problems.” The IBR is a highway project, not a climate project.

Exhaust and Mirrors on the Environmental Impact

With what is likely the only highway project in either state to ever have its own dedicated “climate officer,” the IBR, even after declining to update the purpose or need of the project to directly include emissions reductions, is trying to put the potential environmental impacts of the project front and center in its messaging.

“This project is taking the issue of climate, and impacts to the climate, tremendously seriously,” IBR program administrator Greg Johnson told legislators in December.

So far the project team says it has quantified the emissions reductions that it says the project will prompt. Through the inclusion of more frequent transit across the river and improved walking and biking infrastructure 11,000 daily trips will be converted from vehicle trips to those lower emission modes, allegedly causing a reduction of 36,000 metric tons per year. But the project continues to tout emissions reductions that will come another way: speeding up travel on the highway itself.

“We think we can do better than that [36,000 tons] via a number of different tools,” Johnson said. “One of those tools is to keep traffic moving. We know that when folks are slowing down, that you start burning fuel inefficiently and that’s when you start producing additional greenhouse gases.”

But while the IBR wants to take credit for the emissions reductions that come from shifting 11,000 daily trips from cars to transit, walking, or biking, it doesn’t seem ready to take any blame for additional trips that would come from a higher capacity I-5 bridge. While highway departments can try to twist the data, more cars mean more emissions even if they’re traveling a bit faster, particularly when looking holistically at the system.

Between the time that the traffic counts conducted for the original Columbia River Crossing were completed in 2005, and 2019, the current I-5 bridge has only seen an increase in non-freight traffic of around 4%, or approximately 400 daily vehicles added per year. That’s during a timeframe when Clark County, in Southwest Washington, saw an increase in population of 13% in just the decade between 2010 and 2020.

Between 2005 and 2019 the I-205 bridge, the only other crossing of the Columbia in the Portland metro and which generally sees less traffic congestion than the I-5 bridge, saw an increase of over 14%. The I-205 bridge has four lanes in each direction to I-5’s three. So far, there’s no acknowledgement of the additional trips by vehicles that could be generated, cancelling out those 11,000 daily vehicle trips whose modes are expected to shift.

The Question of Tolling

That oversight likely due to the biggest cloud hanging over the project right now: the issue of tolls. The project’s current finance plan now assumes that $1.2 billion to $1.6 billion of the enormous project cost will be covered by user fees. Those fees, which will have to be approved by both the Oregon and Washington transportation commission, will clearly play a big role in just how much traffic the interstate highway sees, along with whether I-205, as the only other Columbia River crossing, is tolled as well: currently Oregon is moving forward with a separate project to look at tolls there.

The idea of being dependent on user fees for so much of the project cost is a frightening prospect for any Washingtonian familiar with WSDOT’s tolling program. A downturn in revenue forecasts from tolling on I-405 in east King County, intended to pay for a suite of highway expansion projects along that corridor, contributed to the need for a state bailout of the corridor just a few months ago. And of course, there’s the SR 99 tunnel, which had only been counting on $200 million plus ongoing maintenance to come from user fees, and is now facing “permanent reductions” in revenue and a similar need for a state bailout.

The Columbia River Crossing project assumed that on the high end, tolls could be counted on around $1.5 billion in project costs, adjusted for modest inflation, and so far that hasn’t really changed. But the goals of a tolling program that is maximizing revenue are very different from the goals of a tolling program that is managing demand. Models developed for the Columbia River Crossing assumed that by 2036, long after the bridge was open, 39% of traffic would be diverting away from I-5 and another 10% of river crossing trips would be priced out of existence. But with tolls still in play for I-205, the outcomes could be very different.

Currently the IBR team is conducting a full revenue assessment on the potential impact of tolls, but it’s not clear how the robust assumptions currently baked into the finance plan will take into account future downturns in revenue. Everything appears to be hinging on the fact that there are few alternatives to I-5, and so the toll program will be more robust than some of the others that have been implemented around the region.

In the wake of the new cost estimate, the IBR program is quickly turning to blaming anything that delays the project as responsible for any future cost increases.

“Anything that shifts our schedule from our current target that we’ve been stating, could add a significant amount of costs,” assistant program administrator Ray Mabey told lawmakers this month. In other words, the only prudent and financially responsible thing is to move forward as expeditiously as possible. The runaway train may get more expensive if we slow it down.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t anyone pushing to slow the project down and make it better. The Just Crossing Alliance, an entity made up of leaders of environmental justice and transportation-focused organizations from both states, has been pushing for its core assumptions to be reassessed. That group has been pushing to analyze the financial basis of the project more thoroughly before moving any forward, and it continues to push for the centering of the replacement of the river crossing itself over the highway interchanges.

“We invite committee members in both states to right-size this project to create a safe crossing with better transit and active transportation connections, and not to expand highway capacity which would increase pollution that causes health harm today and makes the climate crisis worse,” Paulo Nunes-Ueno of Front and Centered, an alliance member organization, said after the new cost estimates were released.

Even the Seattle Times editorial board is urging more careful consideration, while at the same time decrying “Oregon sloth” due to the delay in the state legislature in coughing up their matching dollar amount.

“The current Interstate Bridge is woefully inadequate,” the editorial board wrote earlier this month. “But whether the proposed replacement with all of its bells and whistles is the right plan is worth lawmakers carefully considering in light of rapidly escalating costs. Washington lawmakers should ensure that Oregon pay its fair share and that Washington isn’t opening a spigot of money it won’t be able to close once construction is underway.”

Of course, by bells and whistles the board likely means rapid transit, which is as tied to the project as the seven interchanges and the river crossing. But at this point in time, it looks like the momentum behind this megaproject has grown so strong that its backers would have Washingtonians believe it’s become completely inevitable and there is nothing that could be done on the Washington State side to slow it down.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.