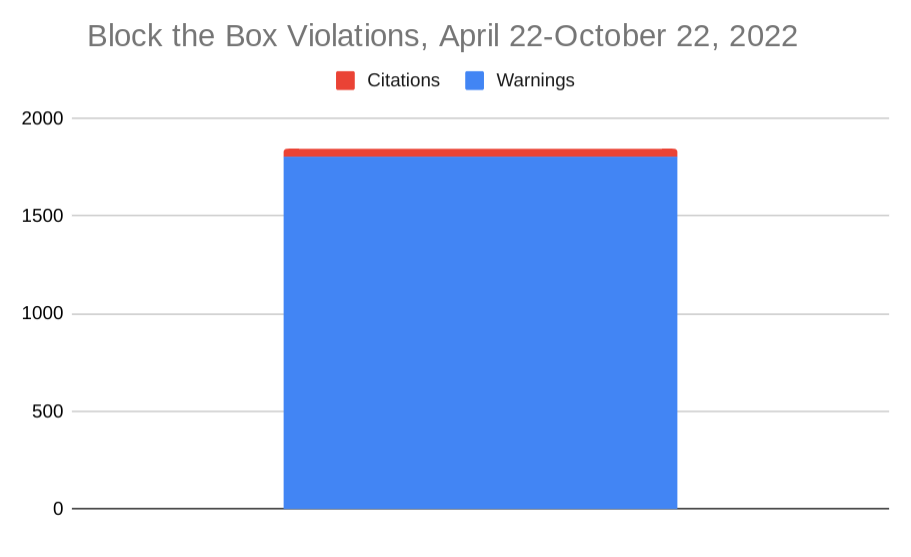

The new intersection cameras issued over 1,800 warning tickets to blocking drivers within the first few months of the program, but only 34 official citations.

Earlier this year, Seattle became the only city in Washington to start issuing automatic citations to drivers for blocking crosswalks and intersections while pedestrians have the right of way. The city’s unique authority to issue those citations, secured in 2020 after a several year battle, is time limited and currently set to sunset after 2025 unless the legislature extends it. A large part of making any case for it to become permanent it will hinge on the issue of how effective the camera citations are at changing drivers’ behavior.

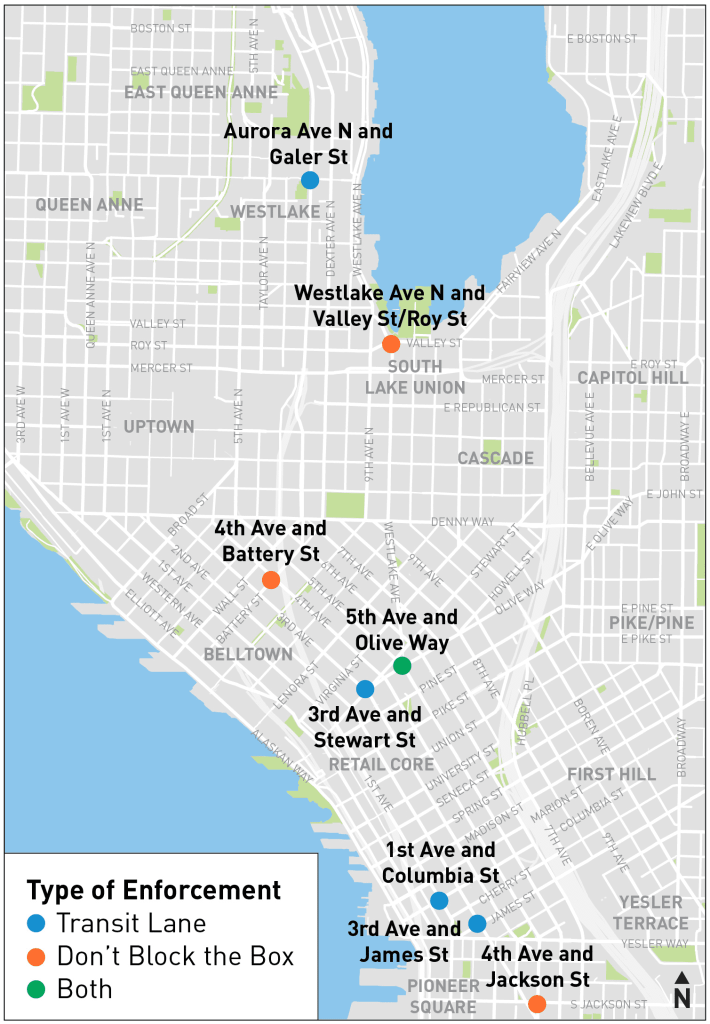

Newly obtained data obtained by The Urbanist on the number of citations issued during the first few months of the program suggests that the four “block the box” cameras are effective at doing just that. Between the time that the four cameras were activated, in April and May of this year, and mid-October, just 34 citations with a fine of $75 were issued, compared to 1,807 warning citations. Data on citations was provided by the Seattle Police Department, which is required by law to analyze the photos taken by the cameras and issue citations.

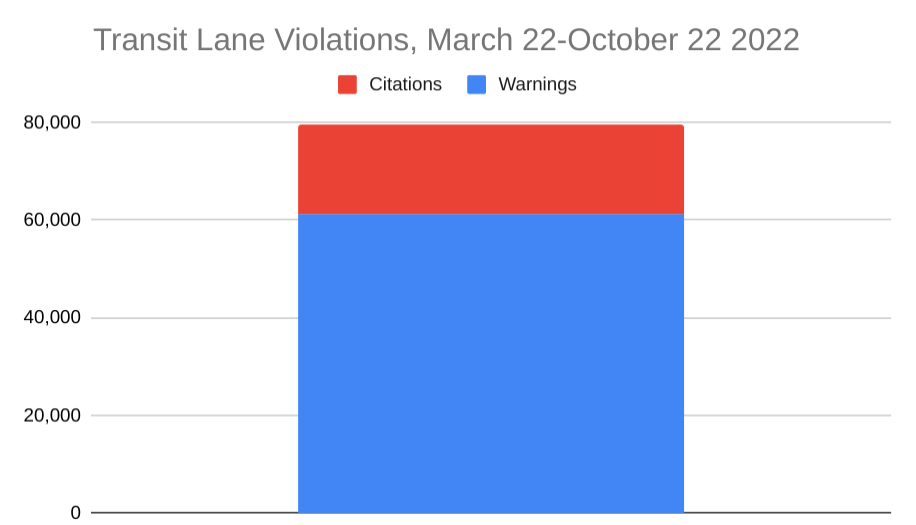

That ratio of warnings to citations is much lower than the city saw over a similar length of time with its new dedicated transit lane cameras, installed at five locations around downtown. There, the City has issued 18,198 citations through mid-October compared to 61,287 warnings. A majority of those five transit lane cameras had been activated approximately one month earlier than the four block-the-box cameras. But, both the transit lane and block-the-box cameras all included a one-month grace period after each camera’s activation where only warnings were issued, which means some drivers could have received multiple warnings during the first month the cameras were activated. The rate of re-offending drivers in the transit lanes, at close to 30%, was almost sixteen times higher than the re-offense rate for the block-the-box cameras.

On its face, it isn’t entirely surprising that drivers would be less likely to continue blocking the box at specific intersections once they were given a warning, compared to transit lanes. Using a bus lane to bypass traffic conveys a much bigger benefit in-the-moment than encroaching on an intersection. But the small number of citations issued for blocking the box, compared to the number of warnings, suggests drivers are getting the message about blocking specific intersections.

The real test for the block-the-box program would be the deployment of cameras to higher volume intersections where intersection blocking is even more prevalent than the ones with cameras now. In 2019, Rooted in Rights highlighted the high incidence of box blocking along Mercer Street, where the wide turning radii that came with the full corridor rebuild a decade ago encourages intersection blocking. But when the initial locations were selected, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) cited logistical hurdles that prevented cameras from being added to Mercer Street as opposed to any of the intersections selected. The City has the authority to deploy block-the-box cameras at fifteen more intersections — assuming it keeps the ones currently in place active moving forward.

Seattle’s first foray into transit lane camera enforcement, in the very unique situation of enforcing use restrictions on the lower West Seattle bridge while the high bridge was closed for repairs, showed that a great number of people were willing to pay the cost of the $75 fine to get where they needed to go. Reporting from Publicola last month revealed that hundreds of drivers still owe the city for their low bridge violations, with several drivers racking up more than 300 citations in 2021 alone. Wherever the cameras are situated, transit lane cameras are likely to continue bringing in revenue to the city, even if it’s unlikely they’ll ever generate as much as West Seattle’s low bridge camera did.

SDOT, overseeing the camera program itself, says it’s too early to draw conclusions from the data.

“While we’ll need some more time to fully understand these numbers, we did expect that block-the-box enforcement would lead to fewer citations than transit lane enforcement due to the lower likelihood of an individual vehicle being caught on camera,” SDOT’s Ethan Bergerson told The Urbanist. “Some people may be illegally driving in transit lanes every time they pass a particular location, even during off-peak times of day. But people generally only block crosswalks or intersections when they are at a certain position in the traffic signal cycle (i.e., the first car in line before a traffic light at a moment when there is the opportunity to enter an intersection but not enough room to clear the intersection) and at times of day with heavy traffic queues.”

Bergerson noted that an evaluation of the program is due to the legislature but not until summer of 2024.

Securing permanent authorization from the legislature for these cameras, potentially expanding that authority to the whole state, could face some headwinds. The initial proposal came under fire from Republicans as well as some Democrats, who argued that the restrictions would be confusing. Even after the legislation had passed, Senators Kevin Van De Wege (D-Sequim) and Lisa Wellman (D-Mercer Island), and Representative Mike Chapman (D-Port Angeles) complained via press release about Seattle’s plans to use the authorization. It’s unclear if the lengths that Seattle went to make sure drivers received a warning before any citation, including posting signs well before warnings were even authorized and issuing multiple warnings over the first month each camera was activated, have done anything to assuage those concerns. Of course, allowing cities across the state to enforce restrictions in the same way would also help to dismantle the argument that special programs in Seattle are confusing — a straitjacket the legislature imposed itself.

With many cities eager to find an alternative to uniformed police officers enforcing traffic laws, Seattle’s pilot program could prove that targeted camera deployment doesn’t just generate revenue, but that it can prompt behavior change — The Urbanist will be watching to see if this early trend holds true in the long run.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.