On Wednesday morning, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell signed an executive order impacting numerous departments across city government, all dealing with the issue of reducing carbon emissions from transportation. Many of the 23 actions listed in the order were either already in progress or previously announced, but it did include one new commitment with a significant potential for the future of Seattle: the creation of three “low-pollution” neighborhoods across the city within five years.

That commitment builds on one made five years ago as part of the C40 Cities “Green and Healthy Streets” declaration: to create a “major area” of the city as completely zero-emission by the year 2030. Many of the signatory cities to that declaration like London, Bogotá, and Oslo have made significant progress on that goal. Any progress in Seattle toward it zero-emission zone goal was largely invisible, until The Urbanist obtained a draft proposal that had been created for now-departed Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) Director Sam Zimbabwe last year.

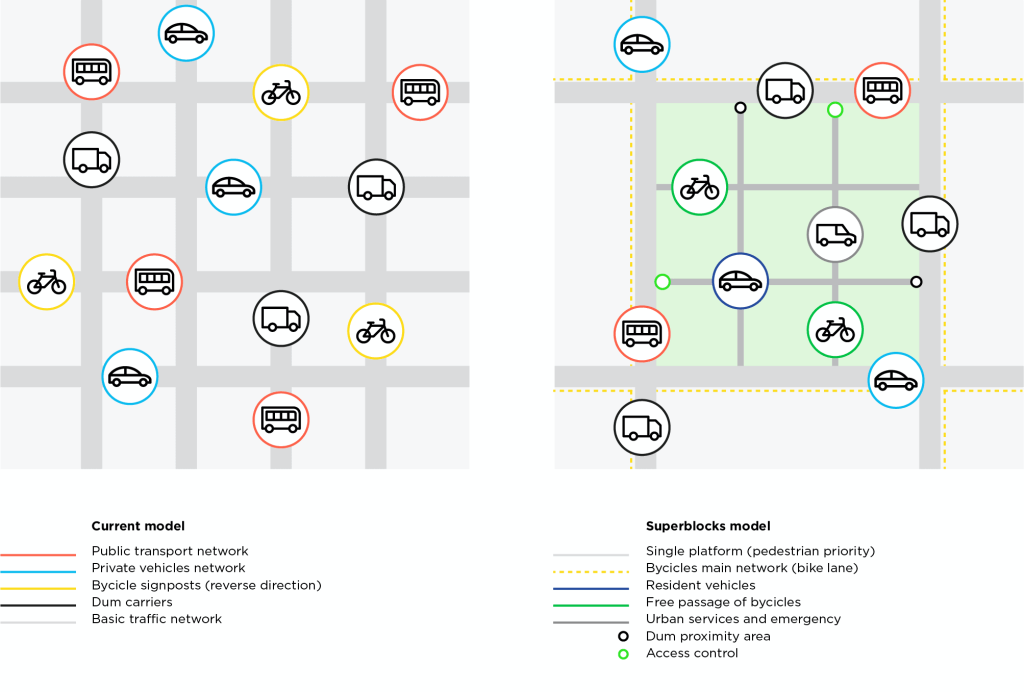

“In 2023 this will include convening a community conversation aimed at planning low-pollution neighborhoods (like low-emissions zones, eco-districts, resilience districts and super blocks) that will align with the goals of the Seattle Transportation Plan and can inform investments in a future transportation funding package to replace the expiring Levy to Move Seattle” in 2024, the executive order states. That overly broad language leaves the door open to multiple strategies, with several options on the table likely presenting bigger political battles than others.

The superblock strategy, in which a neighborhood’s internal streets are only open to specific types of vehicle trips, has been put on the table in the past by leaders like Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda, who recently resurfaced the idea of creating a superblock in the Pike Pine neighborhood of Capitol Hill. Mosqueda joined community leaders and SDOT Director Greg Spotts on a walking tour to conceptualize what a superblock could look like and possible hurdles to implementation this fall. The event that was followed by some behind-the-scenes pushback from local business owners, who will likely be one of the hardest groups of stakeholders to gain approval for a project in any neighborhood.

Creating a superblock in a transit-rich neighborhood like Capitol Hill, a worthy goal on its own, is not exactly aligned with what the administration appears to be seeking, which is finding a way to alleviate some of the incredibly detrimental health burdens that are currently placed on areas of the city by compounding factors in our transportation system.

“The city can’t fight wildfires, but we can reduce chronic exposure to particulate matter, from heavy duty trucks, from the impacts of not having clean energy heat pumps in your own homes,” Office of Sustainability and the Environment (OSE) Director Jessyn Farrell said. “When you look at the data…you see those port-adjacent neighborhoods, South Park, Georgetown, continue to have the dirtiest air, you see those neighborhoods that are adjacent to I-5, like Beacon Hill, continue to have the dirtiest air, and are most impacted, not just in an acute event like smoke, but also throughout the year.”

A process laid out in the order will dictate the areas of the city prioritized for pollution reduction efforts, which will clearly go hand-in-hand with increasing transit access and walking and biking improvements.

“We’ll look at where the data leads us in terms of neighborhoods most impacted,” Harrell said at Wednesday’s announcement. “We know that even the life expectancy [is reduced] in certain areas because of greenhouse emissions and, quite frankly, it’s just bad air, I’ll put it that way.”

In an interview following Harrell’s announcement, Jessyn Farrell said that the city would be focusing on strategies that have been proven to work for shifting commute trips — transit, parking pricing — to non-commute trips, with an intentional focus on school-related trips.

The executive order states that the city will commit to expanding School Streets, a pandemic-related program that aimed to discourage direct pick-up and drop-off immediately in front of some school buildings across the city. Currently at just nine schools, the A-frame signs haven’t served as much of a real deterrent to through traffic. To be truly effective, the School Street program would need to fully pedestrianize blocks outside school doors. In Eastlake, TOPS K-8 school has been a model of this working for decades, with a pedestrianized block of Franklin Avenue E a beloved neighborhood fixture that would likely produce public outrage if it were proposed to be opened to through-traffic.

The text also includes a commitment to “ensure an all ages and abilities bicycling facility serves every public school”, a meaningful commitment only if the city takes the definition of “all-ages-and-abilities” seriously, applying design standards to neighborhood greenways to reduce traffic diversion.

The order also reaffirms the 20 miles of “permanent” Stay Healthy Streets that were committed to by Mayor Jenny Durkan — but not fully funded. Advocates have been frustrated by the roll out of the “permanent” program, which haven’t substantially changed the game on those neighborhood streets by leaving traffic patterns in place. They’re essentially just neighborhood greenways with slightly more stringent signage and barriers. The next transportation levy will clearly need to include a significant amount of new bicycle infrastructure, making this 20-mile commitment pretty unremarkable.

The order also includes an action item related to bus-only lanes on city streets. “SDOT shall continue to invest in a network of bus priority lanes on major arterials through the Seattle Transit Measure and Move Seattle Levy, so that as our city grows, transit is a reliable, effective way to move around the City,” it states.

Adding a long-promised northbound bus only-lane to Rainier Avenue north of Columbia City has been one of the Harrell Administration’s most noticeable new initiatives, but rolling out transit lanes in the city has always been a piecemeal process. Data from King County Metro clearly shows that buses are sitting in more traffic than they were just a year ago, as traffic volumes continue to increase. SDOT had been developing a formal policy to guide the implementation of bus-only lanes, an effort that predates Mayor Harrell’s administration, and this order codifies that policy as being finalized next year.

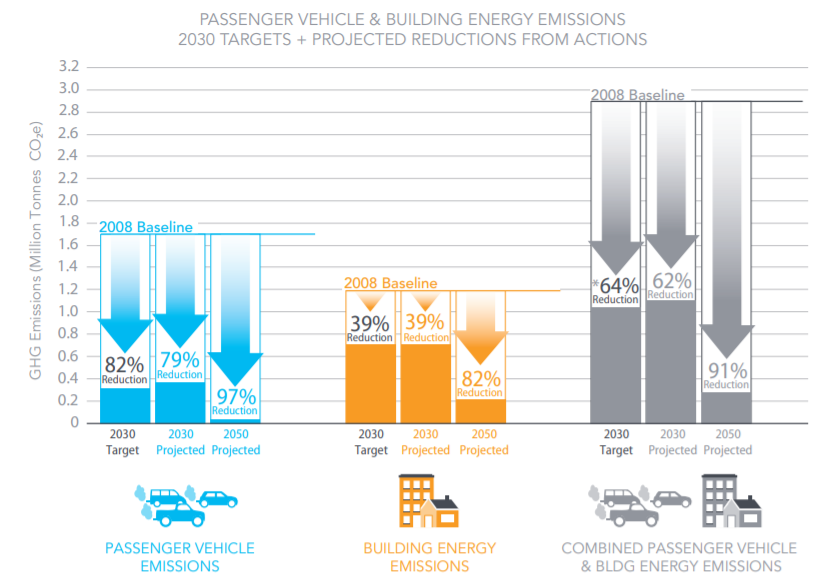

Ultimately, the executive order consolidates in one place a number of commitments that will bring the city forward toward its climate goals, small step by small step. Since the adoption of the Seattle Climate Action Plan in 2013, the city as a whole has not made durable progress toward those overall goals, in part because every subsequent new Mayor served as a reset on the city’s climate policies. Put simply, greenhouse gas emissions haven’t been going down like they were pledged to do.

Long-range plans and vague commitments have abounded, but a clear vision and action in the here and now has been lacking. The order adds to the morass of plans and plans to make further plans, but is short on substantive near-term actions. Electrifying various fleets of cars is a focus, but reducing vehicle miles traveled — also a needed ingredient to meet goals — goes unmentioned. While formerly pledged under Durkan, road pricing also is absent. Meanwhile, Sound Regional Council has deemed road pricing as the most essential policy to meet its regional climate goal.

With journalists more eager to discuss his proposals around homelessness response and crime, The Urbanist was the only outlet at the Mayor’s announcement signing this order who had a single question on the topic. Nonetheless the climate catastrophe looms and Seattle is not on course to meeting its pledges. Every step of progress achieved will be incredibly worthwhile, even as the cumulative climate actions are well below what should be happening.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.