The pedestrian safety crisis has been worsening in Washington State and across the United States, even as most other industrialized nations have taken strides to reduce their traffic fatality rate in recent years. Emily Badger at the New York Times recently did a feature on this troubling phenomenon which provided some extra focus on the topic. On Tuesday, our transportation reporter and senior editor Ryan Packer was on KUOW’s Soundside program to break down the trend along with Yonah Freemark, a researcher with the DC-based think tank Urban Institute.

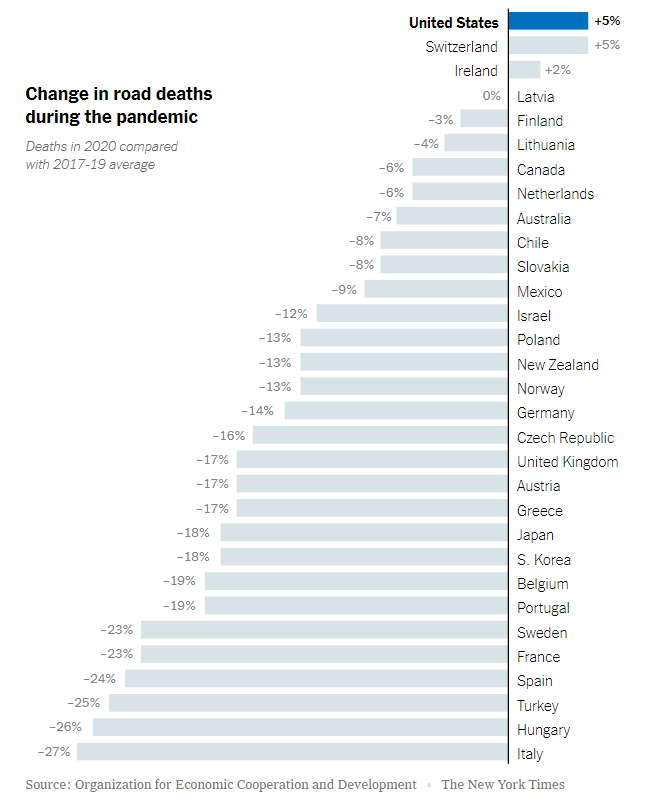

The traffic safety crisis has many causes, and on nearly all fronts American governments are falling short of their global peers on interventions. The proof is in the data. Nearly 43,000 people died on American roads in 2021 according to official estimates. Among the 37 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations, the United States has had the highest rate of road deaths per capita since 2017.

“We’re continuing to see a big increase in the number of fatal and serious crashes on the roads in Washington,” Packer told Soundside host Libby Denkmann. “In recent years, 86% of people walking and biking who’ve been killed in Washington, have been killed on streets with a 30 mile per hour posted speed or higher.”

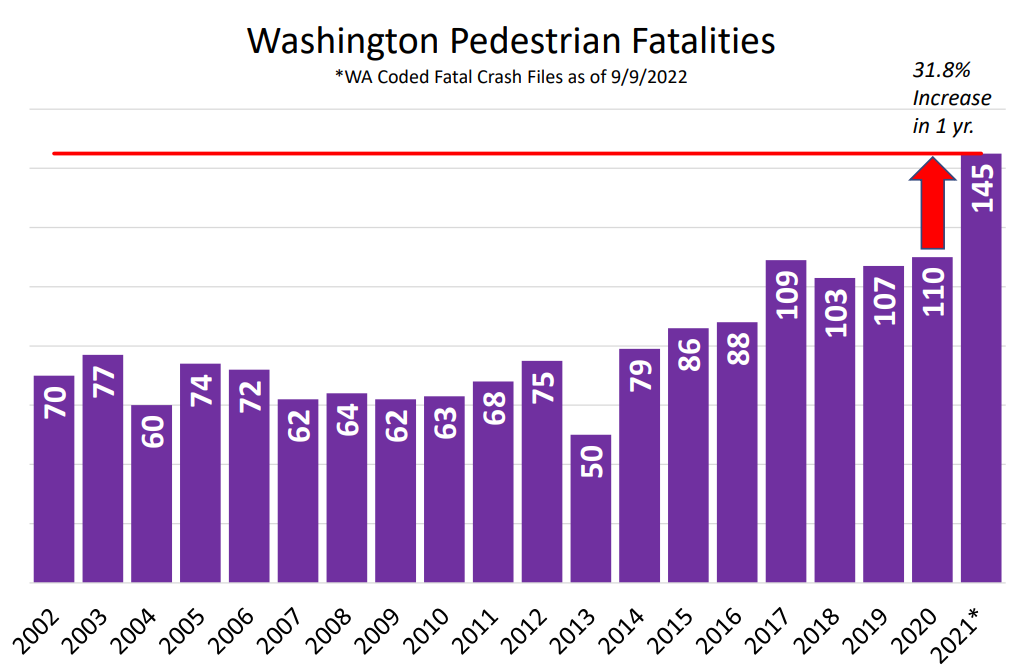

The number of pedestrians involved in fatal crashes has been at the heart of Washington’s spike in overall traffic deaths. Last year, the state saw nearly 150 people walking lose their lives on our streets, a 31.8% increase in one year and the highest figure seen in at least several decades. That trend is not showing any signs of slowing in 2022.

Many American jurisdictions, including Seattle, Bellevue, and Washington State, have set “Vision Zero” goals of eliminating traffic fatalities and serious injuries by 2030, following in the footsteps of a pioneering campaign in Sweden that greatly reduced traffic fatalities through design interventions. Unfortunately, American cities, in contrast, have made far less progress in actually achieving their Vision Zero goals, and have seen road fatalities trend up in recent years.

The pandemic helped accelerate safety progress in many nations, but the United States was again the exception, with the road fatality rate spiking during the pandemic, leading to an increase in fatalities even as vehicles miles traveled declined due to work-from-home provisions.

Check out the episode on your preferred podcast service or listen below.

Packer and Freemark stressed that the traffic safety crisis can be solved. It’s an engineered crisis stemming from design failures. We often touch on these topics at The Urbanist, but it’s helpful to review lessons learned from cities that are seeing major progress toward eliminating traffic deaths and from leading research. Here are a few:

- Road design: American transportation departments have been far less aggressive in redesigning their streets with safety and lower speeds in mind. While many European, Asian, and Latin American cities have seen widespread pedestrianization projects and connected safe bike networks, such interventions are relatively rare in the U.S.

- Urban design: American cities continues to put housing growth, jobs, and amenities in auto-dominated areas beset with dangerous high-speed roads. Putting jobs and commercial activity on wide arterial roads perpetuates unsafe interactions between pedestrians and high-speed car traffic that can prove deadly. Statistically, it’s a fatal crash waiting to happen.

- Vehicle design: American automobiles are bigger, heavier, and have fewer safety features, particularly directed at pedestrians. The physics is clear. Heavier vehicles are more likely to kill people walking, rolling, and biking in crashes. Features like high hoods and bull bars increase the risk further by delivering vehicular impact on pedestrians higher on their body closer to vital organs while increasing the risk of being pulled under the vehicle and crushed.

- Underfunded transit encourage more Americans to drive. American cities provide lower transit service levels than peer cities abroad. Lower frequencies mean transit trips take longer, which encourage people to use private vehicles instead. This leads to more cars on the road, increasing the odds of a collision.

- Lax enforcement: While design is the major difference between the U.S. and its counterparts, it should also be noted that some other nations have stiffer consequences for killing or injuring somebody with a car or operating a car while impaired — and they’re more likely to actually impose them. American authorities have a tendency to blame the victim walking, rolling, or biking rather than hold motorists accountable for crashes. Washington cities have an option to expand camera enforcement, which has the potential to be more equitable.

“Other developed countries lowered speed limits and built more protected bike lanes,” Badger and co-author Alicia Parlapiano write in the New York Times. “They moved faster in making standard in-vehicle technology like automatic braking systems that detect pedestrians, and vehicle hoods that are less deadly to them. They designed roundabouts that reduce the danger at intersections, where fatalities disproportionately occur.”

While it is shameful that American cities are falling behind, the silver lining is that all American cities need to do take a huge leap forward is adopt interventions that other cities have pioneered and proven out in practice. The missing ingredient is political will — not a new technology or policy innovation. The politics of street redesigns, land use changes, and parking are not easy, but they are surmountable, especially if we can center our traffic safety goals in our decision-making.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.