When the King County Council unanimously approved its gigantic $16.2 billion dollar 2023-2024 budget in mid-November, there was a broad consensus on the council that the two-year plan for King County Metro, which makes up 20% of the county’s budget, will set the state’s largest transit agency on a positive path. Even amidst a national shortage of transit operators, councilmembers touted what the investments were poised to be able to provide for riders using the system, and riders who had stopped riding during the pandemic.

County Executive Dow Constantine’s proposed budget, with added amendments by the council itself, adds funds to address a perceived lack of security on the transit system, with $21 million earmarked to double the number of transit security staff on buses, and $10 million to address cleanliness of Metro stops and bus interiors. There is even funding to stand up public restrooms Metro’s transit centers in Burien and Shoreline.

“We heard from transit riders on their strong desire to come back, to use Metro transit, but asking that we make it safer, and that we make it cleaner, using real simple terms: cleaner stations and clean the buses and make it welcoming,” Councilmember Rod Dembowski, who represents northeast Seattle, said ahead of his vote to approve the budget.

But one thing that didn’t receive as much attention from councilmembers was the reliability of the transit system itself, as traffic volumes on the region’s streets return to pre-pandemic levels.

Just a few days after the County Council passed that budget, the county’s Regional Transit Committee met to receive the 2022 System Evaluation report for King County Metro. The yearly report details performance down to the route level, and outlines a path forward for transit service that aligns with the agency’s guidelines. The report, which looked at system performance from this past spring, outlines the bad news when it comes to schedule reliability: the number of late trips across the system is up dramatically compared to 2021.

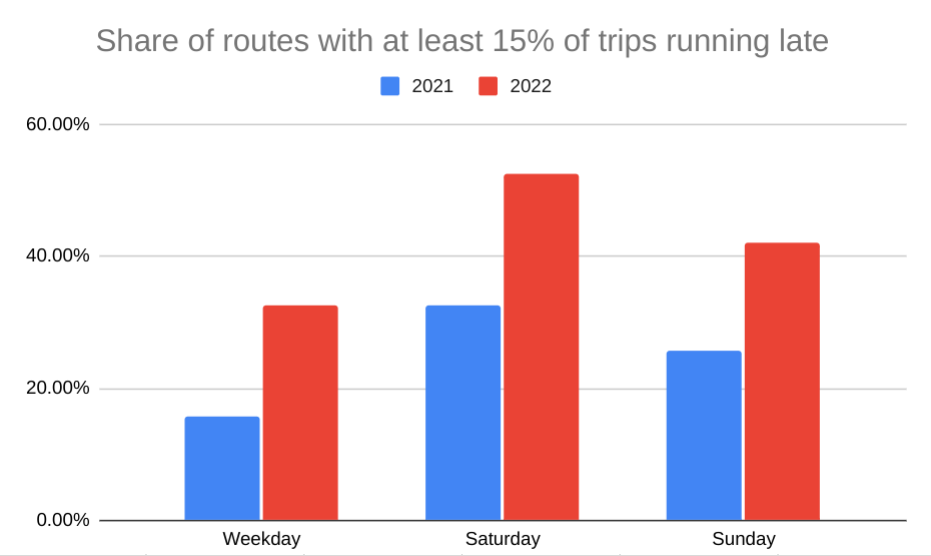

The data shows that on weekdays, over 20 routes are running late on one out of every five trips (20%) or worse while another 24 routes are running late at least 15% of the time — over a third of routes running on weekdays. On Saturdays, the numbers are even worse, with 44 routes running late on at least 15% of their trips, despite many routes in the system not even running on Saturdays at all. That totals over 52% of all Saturday routes. Sundays are a little better, but still worse than weekdays, with 42% of routes running late 15% of the time or worse. For Metro, a bus is considered late if it arrives more than five minutes after its scheduled arrival time at a designated timepoint.

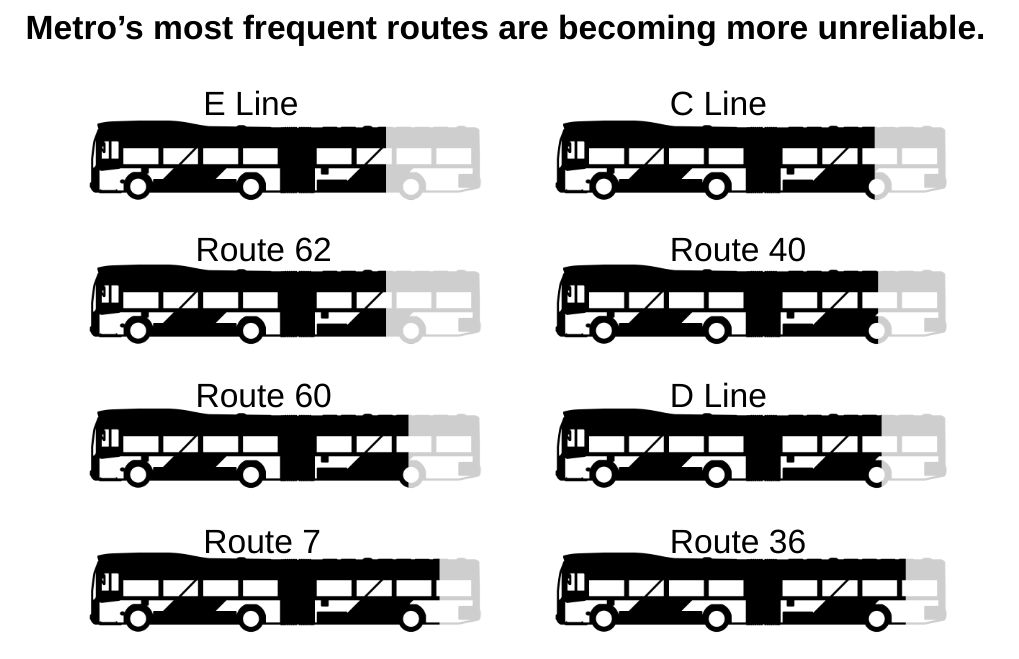

On Metro’s most frequent buses like the E Line, the Route 45, and the Route 8, one in four trips are arriving late on weekdays. For an agency trying to regain ridership, too many late arrivals could be enough to turn off returning riders for several years, especially given the fact that many trips have shifted from being oriented around Seattle’s downtown core and toward neighborhood business districts, schools, and child care facilities.

Of course, Metro battling traffic congestion is not a new phenomenon. In the past, when specific routes began to get bogged down in more traffic, Metro had a specific remedy: add more service. The agency’s service guidelines spell out exactly when the agency should consider adding that service, in the form of adjusting schedules to add more time. But without enough drivers available to cover the additional scheduled time, trips get cut.

Metro’s 2022 system evaluation report explicitly lays out that Metro already needs to add 24,750 annual service hours in order to address reliability on the routes that need it the most: the 40 routes where 20% or more of trips are running late. Hours on those routes would be prioritized before the County thought about adding service anywhere, which the agency’s long-range planning specifically envisions. If reliability continues to get even worse, any gains made in hiring operators could be eaten up before we know it.

A majority of those 40 routes needing investment in reliability are Seattle-based routes. Only a handful operate entirely outside the city, and 26 essentially do not leave the city at all. During the meeting of the Regional Transit Committee, the representatives from the Seattle City Council, Dan Strauss and Alex Pedersen, did not address the contents of the report or the role that the City of Seattle itself is playing in funding transit. With Metro unable to hire drivers, Seattle’s dedicated sales tax has been racking up reserve funds, and the newly adopted city budget siphons $12 million away from those reserves to overall maintenance on the city’s bridges — a move spearheaded by Pedersen.

That’s not to say there are no investments being made that will help bus reliability. Improvements to the Route 40, and the creation of the RapidRide G, H, and J lines, will all create varying degrees of dedicated bus space. But the sharp decrease in reliability between 2021 and 2022 should be a wake-up call for a city and a transit agency that is hoping to do more to service than tread water.

By far, the biggest investment in King County’s capital budget for Metro — the budget for physical projects, not staffing or programs — is the $248.5 million to replace 120 existing diesel-electric buses with battery electric versions. Moving to electric serves the goal of a completely diesel-free fleet by 2035. Metro’s fleet is one of the largest sources of greenhouse gases created directly by the operation of county government, but it is a relatively small subset of overall on-road transportation emissions countywide. If the system is not reliable enough to prove a durable alternative to King County residents’ cars, the overall climate targets will be incredibly hard to achieve.

“I’m pleased that we’re going to be continuing to look at how to make our system welcoming: with clean bus stops, with safety… helping Metro transition to an all-electric fleet and getting ready to restructure Metro services to meet the evolving, post-pandemic transit needs,” King County Council Chair Claudia Balducci said in advance of the budget vote in mid-November.

It’s clear that the county, as well as local governments, will need to accelerate investments in ensuring that buses actually come on time if Metro will fully become the welcoming system that all of the other investments are striving toward.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.