Seattle is poised to divert a major funding source away from public transit and into general transportation maintenance, thanks to an amendment put forward by Councilmember Alex Pedersen during this week’s budget deliberations and approved by a close 5-4 vote. The move could set a long-term precedent, impacting a funding source that for years has been seen as dedicated for transit service and improvements directly related to increasing transit access.

Pedersen’s move, in the guise of providing funding for the city’s “multimodal” bridges, also diverts funding that could be going to transit upgrades in the immediate future as traffic volumes on the city’s streets increase and bus arrival times are becoming more unreliable.

The amendment authorizes the city to use funds from Seattle’s 2020 transit measure for “bridge-related or structures-related transit improvements,” a broad category given that almost all of the city’s major bridges that carry general purpose traffic also carry King County Metro buses. Promised bus service upgrades, voters approved the 2020 measure in a landslide, setting aside a 0.15% sales tax hike for transit. Now, Council is funneling $12 million of this revenue toward bridges just for 2023, and council documents note that a similar allocation in the 2024 budget is anticipated as well. This sets a strong precedent of utilizing the dedicated transit funding source as an ongoing source of bridge maintenance funds.

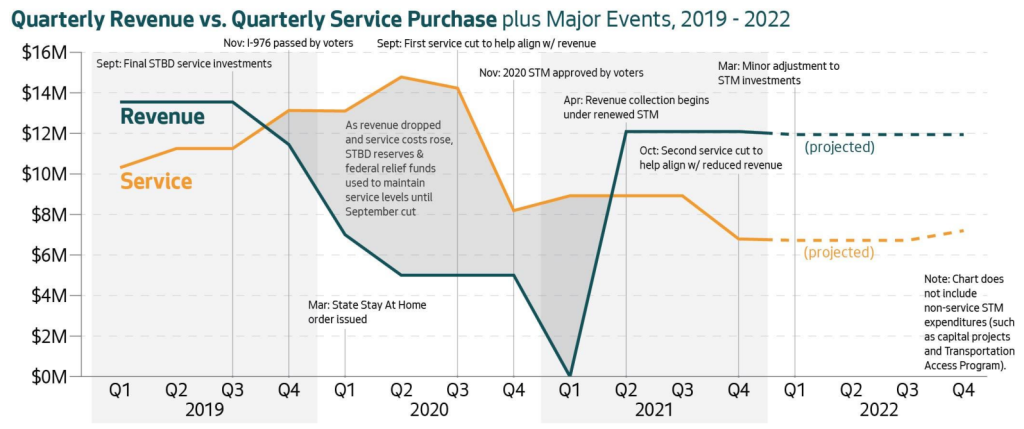

That $12 million is set to come from the Seattle transit measure’s reserves, which have been growing as transit service was cut during the pandemic and Metro struggles to be able to hire operators to provide service. Ever since the 0.15% sales tax started being collected in early 2021, the amounts hitting city coffers have been more than was needed to maintain Seattle’s share of Metro service at current levels. Facing a severe bus driver shortage, Metro only expects to be able to go from a current 87% of pre-pandemic service levels to 91% by the end of 2024, it does look like those reserves are poised to continue to grow. But it’s not clear that repairs and upgrades to bridge structures would have been what the voters had in mind when they voted resoundingly to approve the sales tax measure two years ago.

Pedersen, from his position as chair of the council’s transportation committee, has been trying to increase annual maintenance funding for the city’s bridge structures for several years now. Shortly after the emergency closure of the West Seattle bridge in early 2020, Pedersen requested an audit of the entirety of the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT’s) bridge maintenance program. That audit recommended that SDOT increase its annual spending on bridge maintenance fivefold, estimating $34 million to $102 million per year in ongoing bridge maintenance needs. But neither Mayor Durkan nor Harrell has proposed such an increase or identified a funding source to pay for it.

During last year’s budget, Pedersen received majority support to include an authorization to issue up to $100 million in bonds to provide up-front funding for a slate of bridge projects. Some bridge maintenance was on the list, but a majority of the spending was actually targeted at SDOT’s seismic upgrade program, a completely separate program than the one the city audit examined. At the time, SDOT did not support the proposal to issue bonds, which would have required funding to pay debt service, and earlier this year the Harrell Administration stood behind that position, saying that it was not ready to issue those bonds.

SDOT has been pursuing a number of outside sources for bridge upgrade funding, with President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which passed in 2021, set to allocate billions of dollars for bridges across the country. Earlier this year, the department was awarded nearly $15 million intended for the Spokane Street Viaduct, the Jose Rizal Bridge, and the 15th Avenue NW/ Leary Way NW bridges. Another $15 million in applications have been submitted for the Ballard, Fremont, and University bridges, bridges that were targeted by Pedersen’s $100 million bond proposal. So far, it looks like the city is trying to avoid spending unnecessary dollars on debt service, not avoiding investments in bridges themselves.

Ahead of the vote on this amendment, Pedersen called his proposal “the only way” the city would be able to reach the recommended “bare minimum” annual amount for bridge maintenance.

“I know we’ve been talking about this for three years, and we’ve tried multiple ways to get SDOT to do this. Here we are again, we found a way to do it,” Pedersen told his colleagues. “We’re tapping the reserves temporarily from the Seattle transportation benefit district and increasing the capital allowance even more for the next couple of years, otherwise the money is just sitting there in reserves that are allegedly needed for 2026 or 2027.”

Council central staff’s transportation expert Calvin Chow noted that “future spending would have to be adjusted to maintain a reserve through the end of the 2027 measure” if this level of spending continued to be maintained. It’s easy to imagine a scenario where a future city council decides to continue spending on bridges instead of switching back to transit service even when Metro is able to hire operators. This is underscored by the fact that Pedersen himself didn’t support increasing the Seattle transit measure to 0.15% in 2020, calling a measure at 0.1% “right sized.”

Currently, about 6% of the revenue collected from the transit measure goes toward capital projects: physical improvements that benefit transit riders, either when they’re on the bus or when they’re accessing transit stops. Mayor Harrell’s budget as proposed would have doubled that, primarily due to the fact that the transit measure had been funding ORCA passes for middle and high school students; funds for those passes aren’t needed after the state legislature incentivized transit agencies across the state to make fares free for riders under 18 years of age.

The council’s budget already included a completely new revenue source set to go toward bridges after Pedersen proposed a $10 increase in the city’s vehicle license fee. After a $1.5 million allocation in 2023 to a project in Pedersen’s own district (adding railings and fencing to the NE 45th Street I-5 overpass), the remainder of funding next year from that fee increase will also go toward bridge maintenance. In 2024, around $2 million per year is earmarked to go to bridges every year, with an equal amount going to traffic safety projects citywide. Vehicle license fees are one of the most stable revenue sources the city has at its disposal, with the number of people registering their cars in the city much less variable than, for example, the city’s commercial parking tax which fluctuates along with the number of people parking in downtown garages.

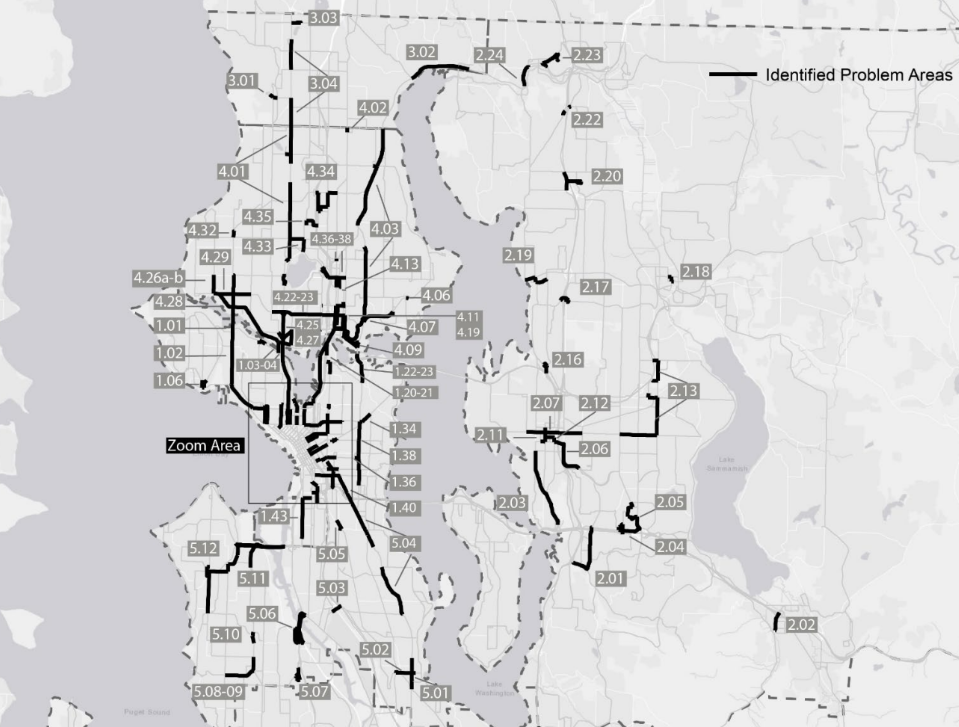

The purpose of the capital spending category in the Seattle transit measure is to allow the city to spend funds on speed and reliability issues that directly impact transit, saving riders time and freeing up driver availability. King County has been directly seeking funds to pay for improvements like that, including proposed upgrades to the Route 36, and the city has also taken the lead on some projects, most notably the large projects like the RapidRide G and the Route 40 Transit-Plus Multimodal Corridor projects. But Metro has identified an entire slew of problem areas where capital spending could speed up buses.

A speed and reliability improvements report finalized earlier this year, that was the direct result of collaboration between Metro and SDOT, identified 34.8 miles of potential improvements in Seattle itself that were considered among the top tier of concepts to be developed into full proposals, which is 65% of the top tier proposals countywide. A major percentage of the places buses are getting bogged down in King County are in Seattle, and the 2020 Seattle transit measure is exactly the right funding source to utilize to speed them up.

The reserve balance could even be used for direct transit-related spending in the form of restoring the $2 million per year that is set to be cut from SDOT’s sidewalk safety repair budget due to a shortfall in real estate taxes. Targeting sidewalks directly near bus stops and light rail stations is arguably even more in the spirit of the 2020 ballot measure than spending on bridge maintenance.

Pedersen’s motion to substitute this proposal with the original one in the budget passed by only one vote, with Councilmembers Mosqueda, Morales, Sawant, and Strauss all voting no. A subsequent motion to directly approve the amendment passed less narrowly, with Mosqueda and Sawant abstaining. Dan Strauss joined Morales in full opposition to the motion, stating that he supported funding bridge maintenance but with funding sources that were “more appropriate.”

Much like the $100 million bond issue, it will be up to the Harrell administration to actually implement Pedersen’s proposal. SDOT will have to identify bridge projects with a nexus to transit: they could take a broad view and utilize the funding for any bridge that a bus runs across, or they could take a more narrow view, keeping additional funding in the reserves. For now though, this looks like a move that could impact transit funding in Seattle for years to come.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.