The Seattle Planning Commission has laid out a bold re-envisioning of public rights-of-way they hope will be incorporated into the 2024 major update to the Comprehensive Plan. A different approach to streets, sidewalks, and alleys can better achieve city goals, the commission contends in a new brief spelling out their vision. The document builds on an earlier recommendation by the Commission, but is much more emphatic in the need to embracing an alternative vision for the 27% of the city’s land area covered in right-of-ways.

“For nearly 100 years, planning and design in Seattle have proceeded from the assumption that the primary function of the City’s public rights-of-way is the movement and storage of privately-owned vehicles,” the introduction to the document notes. “But over the 20-year horizon of the next Comprehensive Plan, several exigencies will require that default assumption to be set aside.”

The brief goes on to note that the city will not be able to accommodate the growth anticipated in the coming decades if streets continue to be used in the same way they are now, stating that the status quo will “literally kill us.” The commission’s brief states: “Rather than declining to zero as the City has pledged, deaths and injuries on our roadways are on the rise, with seniors and children especially at risk. The City of Seattle can neither meet its pledge to mitigate climate change nor adapt to its impacts by maintaining current conditions.”

Among the Planning Commission’s recommendations is the removal of vehicle storage from the current Comprehensive Plans’s list of needs that should be accommodated on city streets. The commission instead is “in favor of a call to develop a citywide parking policy and plan that looks to balance revenue needs with opportunities for multi-function streets that provide more options, public space, and environmental benefits.” Mode shift to transit, walking, rolling, and biking would mean less pollution, especially along the busy arterial roads where the city has funneled most of its new housing.

“The journey toward more equitable, less deadly, and more climate-proof allocation and design of our rights-of-way starts with a clear-eyed policy declaration in the Comprehensive Plan that the longstanding – if undeclared – primacy of private motor vehicle throughput and storage must be set aside. As we have noted, this neither anticipates nor calls for elimination of privately-owned vehicles. It merely acknowledges and seeks to adapt to the accumulating circumstances – rising traffic violence, congestion, climate impacts, and a crying need for travel options and public space – that require us to be more flexible and creative in our use of space than we have allowed ourselves to be in the past.”

-Seattle Planning Commission

The brief is an emphatic push on a City bureaucracy that has been taking a more timid approach to current long-range planning efforts. On Monday, Seattle’s Office of Community Development (OPCD) will be releasing its scoping report laying out what options will be formally studied as part of its housing growth strategy, envisioned through 2044. Many residents were pushing for more ambitious plans than the city had even put on the table, and this week’s report should outline what the outer limits of the city’s ambition will be. At the same time, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is working on merging all of the city’s siloed transportation plans (freight, bicycle, pedestrian) into a single Seattle Transportation Plan. That effort has been conducted separately from the housing side of the Comprehensive Plan, but eventually the two are supposed to align in their final forms, theoretically.

Earlier this year, the Planning Commission raised a concern about the integration of SDOT’s transportation plan and OPCD’s comprehensive plan update, suggesting that the Seattle Transportation Plan is too focused on vehicle electrification, while the options the city’s considering around future land use are by necessity more focused on mode shift.

“Underlying [the comp plan land use] scenarios is acknowledgement that space in the city will need to be allocated increasingly to housing and moving people (as opposed to vehicles), and that current rates of car use and storage cannot be sustained in the context of future space constraints,” a July letter to SDOT signed by the commission’s two co-chairs stated. “The [Seattle Transportation Plan] scenarios, in contrast, appear to assume a future high rate of trip-making by privately owned vehicles, with the only variable being whether those vehicles are electric.”

“We appreciate the intention to evaluate scenarios relative to the City’s stated goals for reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. However, we are concerned that framing the scenarios based on reductions from conversion of private vehicles to electric will miss an opportunity to evaluate alternatives that the City has far more influence over, and that align with the forthcoming update to the Comprehensive Plan,” that letter states.

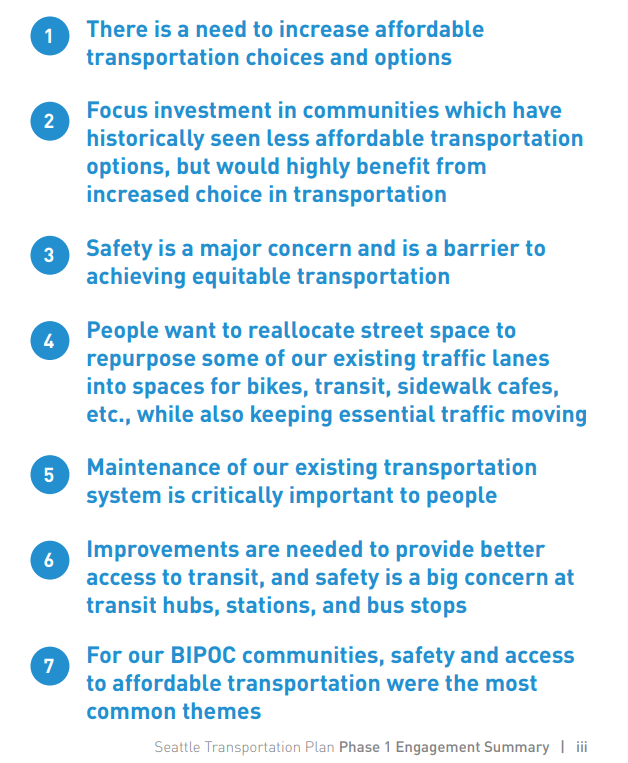

Initial data from SDOT’s outreach around the Seattle Transportation Plan suggests that public opinion is on the Planning Commission’s side: people want see a bold re-envisioning of space for mobility and placemaking in the city. The first phase of public engagement, which wrapped up this August, engaged over 4,000 people, collecting over 36,000 individual pieces of feedback. Among the themes heard as summarized by SDOT were that “[p]eople want to reallocate street space to repurpose some of our existing traffic lanes into spaces for bikes, transit, sidewalk cafes, etc., while also keeping essential traffic moving,” and that SDOT should focus investment “in communities which have historically seen less affordable transportation options, but would highly benefit from increased choice in transportation.”

As the Seattle Transportation Plan heads into its second phase, which is being described as a more detailed menu of options for the city to consider over the next few decades, we should expect the plan to more directly intersect with the options Seattle is considering for its land use policy. For example, if the City is considering expanding the number of urban villages in the city, the resulting transportation policy implications of new nodes of density will become front-and-center issues.

In the brief, the commission doesn’t mince words around the city’s current land use strategy. “The urban village strategy and previous Comprehensive Plans have concentrated growth along arterials that often are busy, dangerous sources of health-harming emissions in neighborhoods with limited public space,” they wrote. “Over the life of the next Plan, the City must prioritize investment in these corridors to prevent traffic violence while providing more opportunities for outdoor activity; improve transit speed and reliability; reduce noise and emissions in residential areas; and increase options for non-motorized travel.”

With the Planning Commission clearly embracing a fundamental shift in the transportation element of the Comprehensive Plan, the question is only how far the Harrell Administration and the Seattle City Council will go in matching that vision.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.