While Seattle’s budget proposal has been grabbing most of the headlines over the past month, the King County Council is also thick in the weeds on how to shape County Executive Dow Constantine’s plan for county spending over the next two years. One of the meatiest topics that the council is dealing with are a whole host of issues facing King County Metro, the nation’s eighth largest transit agency.

The Executive’s budget invests nearly a quarter billion dollars in fleet electrification and $21 million in doubling the deployment of contracted transit security officers, but the budget doesn’t fully restore transit service to pre-pandemic levels or make significant headway in speeding up the rollout of more RapidRide Lines.

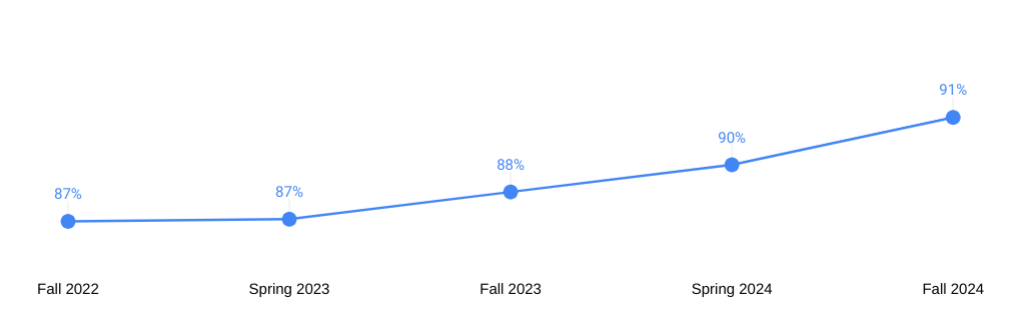

Among the pressures facing Metro are a nationwide transit operator staffing crisis, one of the main factors preventing the agency from returning to service levels that more closely match what had been provided in 2019 prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Throughout this year, The Urbanist has documented how the number of bus operators has been heading in the wrong direction, with fewer available operators month-over-month. Out of the 2,620 operators that the agency currently has the authority to budget for, 269 are vacant; more than 1 in 10 positions are vacant. In planning its two-year budget, King County is only assuming that Metro will be providing 91% of the service hours it provided pre-pandemic by fall 2024, a modest increase compared to today’s 87%.

Even as the county can’t add service back as quickly as it might like, elected officials are trying to shepherd Metro through this uncertain phase and onto more solid footing. Council Chair Claudia Balducci has been out front on that issue and referenced the long-range Metro Connects plan that the council adopted in 2017 but tweaked as recently as last year.

“Our Metro Connects plan actually holds up fairly well through Covid. It was conceived before Covid, but it drives us in the direction of doing more all-day service, more connecting people to all kinds of destinations, and sort-of de-emphasizes, relatively speaking to our past approach, the heavy emphasis on high volume commute routes, so in that regard it was a little prescient,” Balducci said at a budget discussion last week. “I do think there is a certain level of reset out in the world, that you’re not going to see a full return to the level of peak commuting that we had seen before…could we, within this biennium, start to move toward more service, of the type that people seem to be using?”

The proposed budget does plan some spending to address the ongoing operator shortage, but those efforts are largely taking a backseat to the parallel but completely separate effort to renegotiate the county’s contract with the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU). The current contract expires on Halloween, and bargaining is currently underway.

The items directly in the budget to address hiring would include $3.1 million to increase supervisory staff “to provide support and training to bus operators and more easily fill vacancies,” $6.4 million directly for recruitment, with a particular focus on staffing for planned expansion of light rail in the coming years, and another $15.3 million intended to transform the way Metro acquires talent and manages projects. Those tools will likely continue to be less impactful than the big factors impacting hiring: operator pay and the perception of driver safety.

Doubling of Transit Security Officers Planned

In an effort to respond to pressure to improve safety aboard buses and at major transit centers, the proposed budget for Metro would double the number of contracted security officers from 70 to 140. These officers are currently primarily staffed on RapidRide routes now, but have gone from conducting fare enforcement to educating riders about fares. This $21 million add would increase that staff, and would expand a number of specific security programs, including a 24/7 security presence at the Aurora and Burien transit centers as well as having officers at the termination of Third Avenue routes in downtown Seattle at both the Third and Virginia and Third and S Main Street stops so that operators don’t have to resolve issues on their own before heading back to base.

The continued expansion of transit security is being guided in part by Metro’s Safety, Security, and Fare Enforcement (SaFE) reform initiative, which is taking a holistic look at the agency’s fare enforcement and security policies. Having security officers more present on buses was one of the top recommended actions in a survey the agency conducted, with nearly 50% of the Metro employees surveyed ranking it as something they’d like to see, but it was far from unanimous. Included in SaFE are also a slate of non-police reforms to improve the sense of safety on buses, some of which we may see moving forward in the coming months or years. Among those reforms are proposals that would develop an alternative enforcement approach to minor code of conduct violations on buses.

Fleet Electrification

One of the biggest things that Executive Constantine’s 2023-2024 budget for Metro would do is ramp up considerably the purchases of battery-electric buses in response to the county’s adopted goal of transitioning to a fully electric fleet by 2035. This budget is the first that goes beyond a pilot phase for electric buses, and a nearly $250 million allocation in the county’s capital budget would purchase 120 battery electric buses, two electric water taxi vessels, and 19 paratransit minibuses. That’s just a down payment toward replacing more than 1,300 buses that make up the entire fleet. The 2023-2024 biennium is the timeframe when any new buses purchased would run into that 2035 deadline given a usual bus lifespan of 12 years.

The other side of that coin is bus base infrastructure being retrofitted to accommodate all of those coming electric buses. By 2025, Metro plans to open its interim base immediately adjacent to the South Base in Tukwila, with South Base itself opening as the next fully electric base by 2028. Metro isn’t planning on spending any money on electrifying South Base yet, but is applying for a Federal RAISE grant for that project, after being passed over in 2022.

As the county goes all-in on converting the fleet to electric, the tradeoff is with other capital investments that could provide amenities to attract riders, grow service levels, and stay on track toward the Metro Connects long-range vision.

RapidRide Expansion

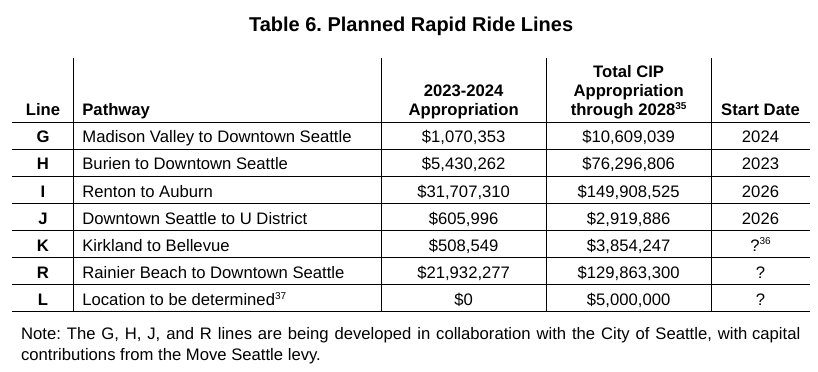

For the most part, the proposed budget is very light on investments in continued expansion of the RapidRide network, Metro’s highest level of service. As the county works toward opening the RapidRide G, H, and J lines, all of which were made possible with substantial funding from the City of Seattle, and prepares to complete full design on the RapidRide I between Renton and Auburn, the rest of the alphabet is on incredibly long and squishy timelines. RapidRide upgrades for Route 40, Route 44, and Route 48 had been pledged in Seattle’s 2015 transportation levy but remain nowhere to be seen after former Mayor Jenny Durkan shelved them in 2018 facing budget shortfalls and minimal prospects for federal grants from the Trump administration.

The highest amount of funding in the budget would go toward another Seattle line: the RapidRide R, which would take the place of the Route 7 on Rainier Avenue. Over $20 million would get the project rolling again after it was paused at 10% design, but “substantial completion” of the line isn’t expected until 2028 and would likely only happen with additional City of Seattle funding or at least significant federal grants. Seattle is already giving Route 7 its own dedicated lanes, which presumably would have been a part of the RapidRide project.

The other line in planning, the K Line intended to run between Bellevue and Kirkland, is on even shakier footing. With design at only 1%, the proposed budget only allocates around $500,000 for work on the project this biennium and a full $3.8 million through 2028, which is incredibly less funding than the budget allocates to the L Line, which is a route that hasn’t even been picked yet but which is also on a fairly unknown timeline.

Initially, Metro staff were even hesitant to say whether the K Line would even be competitive for federal grants, though they appear to be coming around on that issue. The indefinite delay for the K Line is a pretty tangible example of how the county is prioritizing the electrification of the bus fleet ahead of projects that would actually improve service for current or near-future riders.

Figuring out the balance between those two things has now been left to the county council, which will be developing amendments in the coming weeks that will tweak the Executive’s budget. Big changes are not likely, and the most important thing to watch at Metro will be how the dynamics of hiring, ridership, and service levels evolve over the coming year. But it looks like there will be at least a few substantial tweaks coming out of the council intended to help riders using the system right now.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.