A journey into the city’s soft gates and silos.

Here’s an interesting fact: Seattle has fewer 24/7 public restrooms than it does publicly financed stadiums.

That doesn’t sound right. After all, there are only two stadiums and an arena in Seattle. And we have at least that many bathrooms open all night. Unfortunately, that’s both an undercount of our stadiums and an overestimate of bathrooms.

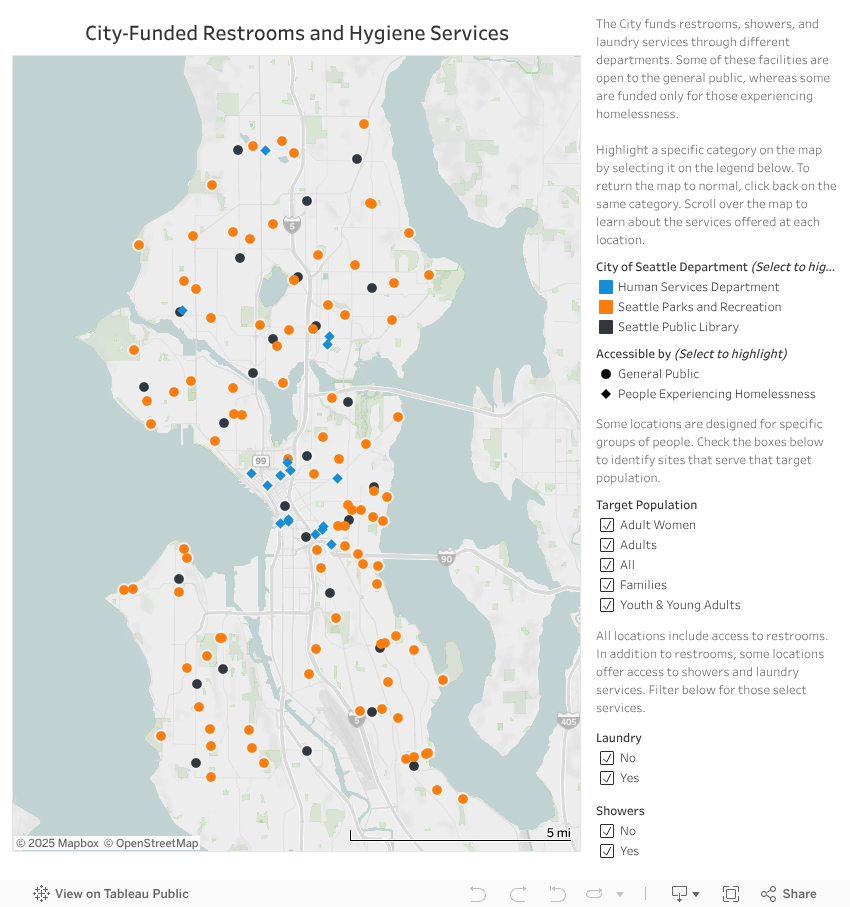

Seattle has produced a number of maps showing the city maintains over 100 restrooms and comfort stations around town. However, as Publicola has often reported, the real count hovers somewhere around 10 when one strips away those hidden behind locked gates or that close with a library. Of the 140 public restrooms identified on the city’s maps, more than half are in parks that get closed seasonally, to the chagrin of parents everywhere. It gets very confusing because there are three different agencies – Seattle Public Library, Seattle Human Services Department, and Seattle Parks – charged with public bathrooms around town.

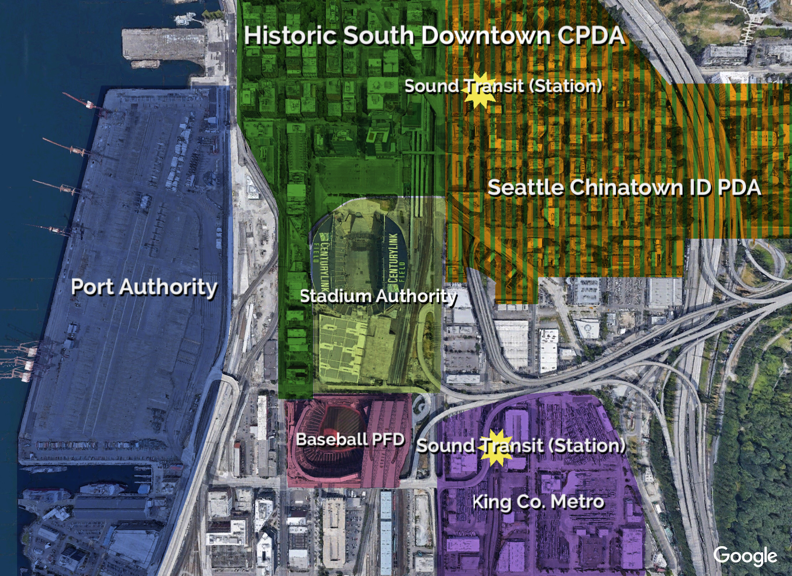

Map of Seattle's Public Restrooms. This map includes all 141 restrooms operated by Seattle Parks, Seattle Department of Human Services, and Seattle Public Library. Interactive map available here: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/owen.kajfasz8040/viz/HygieneServiceMapPublic/Dashboard1Seattle has 14 publicly financed stadiums. They fall under different agencies too, so it’s difficult to think of them together. There are the three big ones for the professional sports teams. University of Washington has at least six facilities that rank – football, basketball, softball, baseball, soccer, and tennis – plus a few more training centers and fields that get really close. Then we can start counting stadiums at high schools around town. Seattle Schools maintains four athletic complexes plus Memorial Stadium at Seattle Center. The number goes higher if we include waterways used for athletics like the Greenlake Aquatheater or the Montlake Cut.

For the record, the combined count of restrooms in these facilities approaches 200 with half at Lumen Field, T-Mobile Park, and Climate Pledge Arena. I couldn’t make an exact count because some of the facilities’ seating charts are better than others at locating the loo.

The question of how we count is an interesting one. Seattle has networks of many different facilities that are publicly funded, but hidden behind weird gates. Or they’re private and treated like a public asset until suddenly they are not. Bathrooms and stadiums are just the top of the list. Artificial barriers prevent us from having a good count of the many resources that are available in this city.

Whose Facility Is It Anyway?

University of Washington is a very useful starting point. As the state’s flagship public university, it exists both integrated with the city and still an island of its own. It’s easy to forget that the school boasts 15 separate public housing towers as well as two publicly funded museums: the Henry Art Gallery and the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture.

What’s really fun is to consider libraries. Seattle Public Library has 27 locations (all on the list for public restrooms). UW adds 16 more libraries. All three campuses of the Seattle Colleges boast at least one library. Seattle University boasts two, but we’ll focus on the law library that’s a Selective United States Federal Depository and therefore open to the public. That brings us to 47. The number goes straight through the roof when 96 libraries at the various Seattle Public Schools are added to the list.

That, of course, brings us to schools. How many are in Seattle? There are 106 schools in Seattle’s public system that educate over 52,000 students. There are also 37 schools who are members of the Northwest Association of Independent Schools and 23 parochial schools that are part of the Archdiocese of Seattle. The size of these schools range from 37 students at Dartmoor School to 1,100 students at Seattle Academy. The line between public and private schools is blurred as Washington funds charter schools. There are eight charter schools in King County. Should their libraries be counted among the city’s resources? How about their playgrounds?

The public private line also drifts for churches as they are public charities who are exempt from taxes. Though Seattle has some of the highest rates of people identifying as religiously “unaffiliated” there are plenty of places to pray. That number could be 510 all the way up to 1,355 depending on how one counts. Alas, my Sundays spent at the corner bar do not appear to qualify that location for tax breaks.

There is one type of drinking establishment for which there’s a pretty firm count. Seattle boasts 92 Starbucks locations, plus or minus depending on which get closed for unionizing. About a dozen are located in public buildings like the UW campus, Seattle Center, or Pike Place Market. Starbucks also brings us back to the discussion of bathrooms. As the pandemic descended, both Starbucks and libraries closed their doors and we found out just how many people depended on these locations for their sanitary facilities.

Mini-Governments Build Many Silos

As we start counting public and quasi-public and private venues, it becomes very evident that there are a lot of separate providers for these services in Seattle. The blurry line between public and private also raises the question of who is governing and policing these spaces.

The trite answer is that there is one Seattle government. It’s also the wrong answer.

Starting from the smallest level, there are hundreds of organizations that govern small pieces of the city. Whether it’s 170 condo associations or the dozens of homeowners associations, property owners subject themselves to extra governance all of the time. Many of Seattle’s schools host Parent Teacher Associations, which I can say from experience are the most local and most emotionally laborious form of government imaginable.

Stepping up a level, there are special taxing districts and public development authorities across the city. These are specialized corporations established by local or state law to perform specific tasks assigned by the legislature. Whether it’s the building homes in the Chinatown-International District or managing one of the stadiums, these are often unelected governments assigned to do a job. Sound Transit and Puget Sound Regional Council are authorities whose boards are selected from among already elected officials. The Port of Seattle is the rare public development authority with specifically elected representatives.

One note: Sound Transit has started to provide public restrooms. But only after an immense amount of pressure, locked behind their station gates, and mostly outside of the city limits.

What becomes very interesting is considering how certain government agencies fall into this arms-length separation too. Seattle Public Schools have their own elected board and do not fall under City Hall. University of Washington has an appointed Board of Regents that answers to the governor. Very interestingly, UW also has a separate, self-sustaining unit called the University of Washington Investment Management Company that organizes the school’s investment portfolio. Kind of triple arm’s length to grow the university’s endowment.

The picture becomes more confusing when considering policing. Each of the colleges in the city has a public safety office with security patrols. UW has a police department, as does the Port of Seattle. The King County Sheriff offers security around the downtown courthouse, serves warrants and evictions throughout the city, and provides a special team assigned to police Sound Transit, supplementing the agency’s own contracted private security force. When there is any discussion of changing the roughly half-billion dollar budget of the Seattle Police Department, remember that SPD is only one portion of law enforcement that operates in the city proper.

This is just a snapshot of the labyrinthine structures that organize our daily lives. These are organizations that get established to refocus authority or separate electeds from direct responsibility of a day-to-day operation. The organizations take on a life of their own with hires and bureaucracy and legislation. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a super-special organization that could cut through this muck, bring down these silos, and have a single government accountable to the people!

Of course, that’s the thinking which created many of these organizations in the first place. A homeowners association to skip the city’s authority and prevent undesirable house colors or even more undesirable neighbors. An explosion in private school enrollment to avoid the hard questions facing the school district. A stadium manager to deal with a sports team and only report good news back to the city (and ask for the occasional roof replacement). A special district to focus the city’s attention on economic development in a certain spot.

Or a Park District to avoid having to change the state’s ridiculous system of funding capital projects through levies. In 2015, Seattle established just such an entity to manage the city’s green spaces. Technically, of the public bathrooms that the city claims are accessible, 97 of them are run by a separate government entity.

It’s one of the absurdities that becomes very apparent when taking a step back and trying to understand a simple question like who manages public restrooms. More than any freeze or public consultation, it is these silos and soft gates that truly define the Seattle Process. Too many official groups and overwrought authorities established out of that desire to cut through the massive bureaucracy. They’re supposed to stand apart from the complexity of the city, but end up adding confusion. The city’s public restrooms, whichever agency runs them, could save a few bucks on paper and just dispense red tape.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.