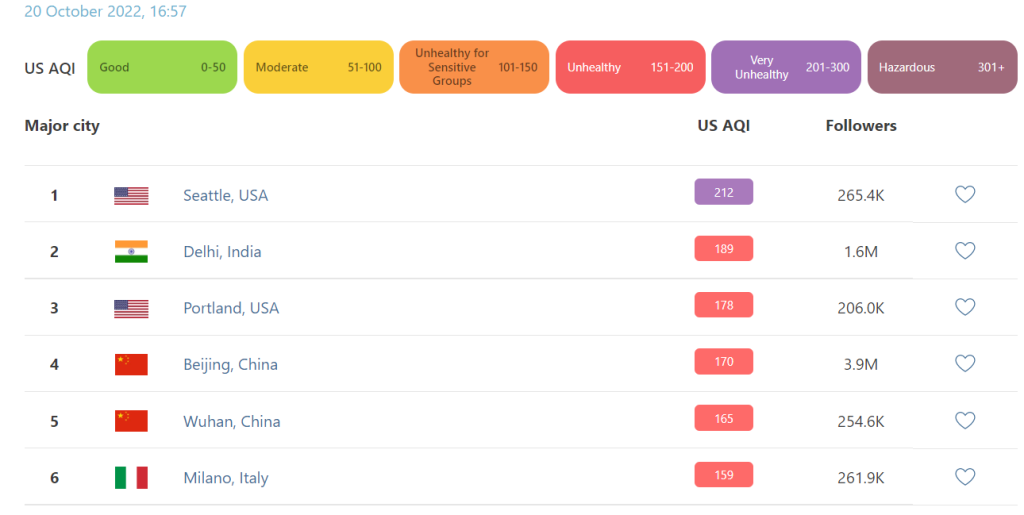

Mayor Bruce Harrell was in Buenos Aires yesterday attending the C40 Climate Summit. Back at home, Seattle’s air quality was rated “very unhealthy” and its index climbed into the 200’s due to smoke rolling in from nearby Bolt Creek wildfires. Ratings on the Eastside (closer to Bolt Creek) were often even worse over the past month of fires. The Seattle metropolitan area had the worst air quality in the world Wednesday and Tuesday, beating out megacities like Lahore, Pakistan and Delhi, India that routinely deal with smog from heavy industry and automobiles.

Fires in the Cascades like the troublesome, long-burning Bolt Creek fire were fueled by an abnormally dry fall stacked onto a dry summer. The Seattle region has not seen significant rainfall since early July. Normally October brings wet weather and ends the wildfire season, but that didn’t happen this year. Climate change is making this pattern more commonplace, raising the specter of even more extended smoke seasons in the future.

Once the inversion system is set due to wildfire smoke layer, tailpipe pollution is trapped in the thick hazy air, creating a double whammy. The resulting particulate heavy air is particularly dangerous for people deemed sensitive groups, such as the young, the elderly, and those with respiratory conditions. The high pollution levels can bring on asthma attacks, fatigue, and headaches. Prolonged exposure takes years off life expectancy.

The stage was set in Argentina for Mayor Harrell to address this crisis and chart a way out. Unfortunately, the Mayor stepped up to the plate and took the pitch rather than swinging for the fences. No new programs were announced, and as Harrell fielded questions on the panel, he frequently pivoted to side issues like mentorship or streetlights rather than digging into the heart of the issue.

Jenny Durkan, Harrell’s predecessor, was also a regular at C40 conferences and dealt with similar issues of legitimacy standing next to bolder mayors like Anne Hidalgo of Paris or Sadiq Khan of London, who have led their cities to significant carbon reductions and climate adaptions. Hidalgo has prioritized people walking, rolling, and biking on Paris streets, rapidly rolling out bike lanes and pedestrianized corridors and aggressively adding social housing, with an ambitious goal of expanding the city’s housing stock to 30% social housing by 2030 — Seattle’s social housing share is sitting at about 8%, meanwhile. Khan expanded an ultra-low emission zone across more of London, with congestion charges raising money for transit and other multimodal investments.

Even if she failed in the follow through, Mayor Durkan at least had a tendency to promise something big at C40, such as road congestion pricing in 2018 — later abandoned after blowing through a $1 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies studying it. Later, she turned toward long-range planning for net-zero emissions public buildings and promoting car electrification. With Durkan there tended to be a press release of some sort ahead of the C40 Summit.

Harrell took a different tact, talking up existing efforts instead of promising something new. Unfortunately those existing efforts aren’t nearly enough. Prompted to delve into his vision for climate action and resilience as it related to impending “One Seattle” comprehensive plan, Harrell dodged and focused on process and branding rather outcomes, saying the plan would avoid divisiveness and include loads of listening to each other. While evoking an image of rich and poor Seattleites of all races coming together as one, absent in his comments was any clue of what would actually be in the plan.

Those planning decisions really are going to get made soon, although the final plan isn’t due until 2024. It appears to be the biggest chance to alter planning for how Seattle grows and builds housing this decade.

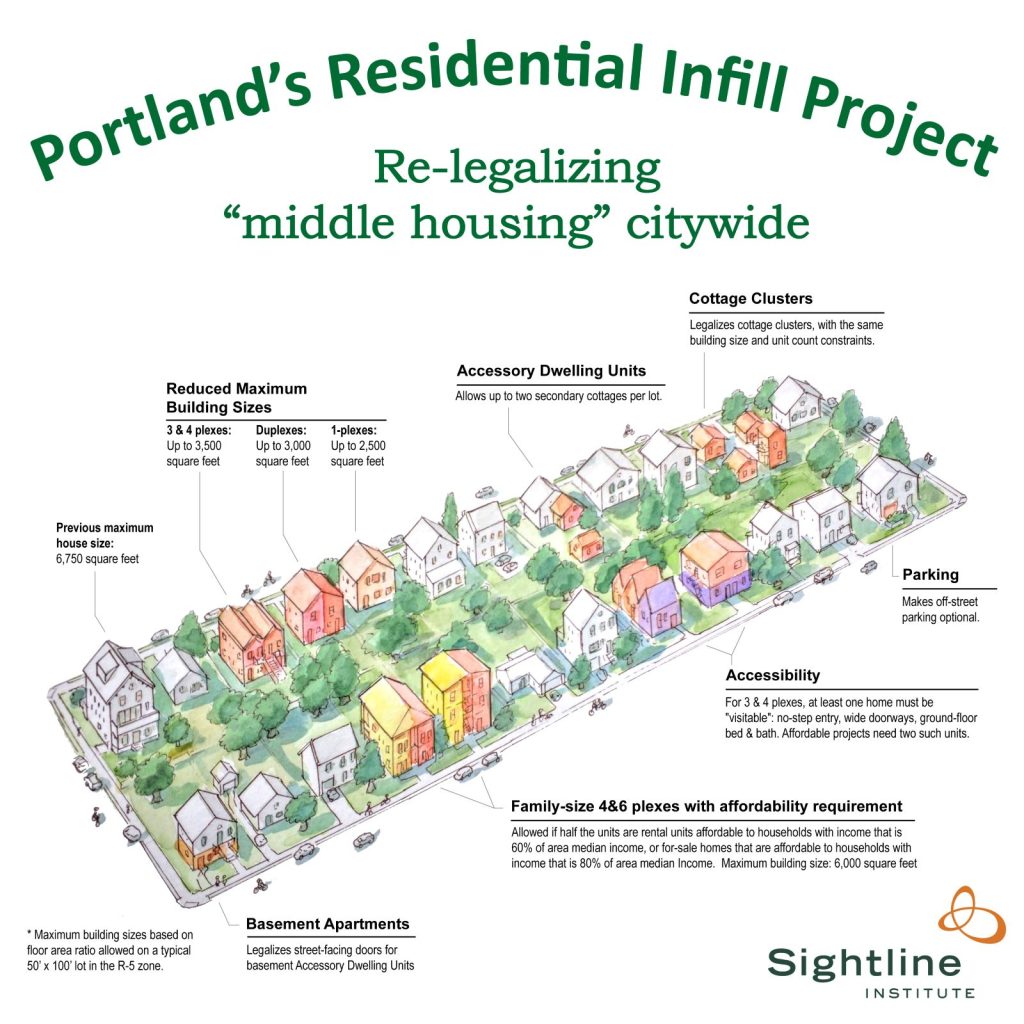

The Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development is due to reveal the final alternatives that will make into the environmental study for One Seattle plan this fall. Advocates have pushed for a bolder “Alternative 6” to be added to the plan that includes more multifamily housing and fully phases out single-family zoning. The catch is that Harrell sharply criticized his opponent for just such an approach while running for office and promised homeowners (a demographic that strongly turned out for him) that single family zoning wasn’t going to disappear.

Once in office, Harrell criticized and declined to sign on to a statewide missing middle housing bill that would largely taken the decision out of his hands by setting a minimum zoning standard, originally drafted as sixplexes near major transit before being watered down in committee. Harrell again leaned on process, arguing for a more “granular” block by block approach to changing anything. That bill died in the house, but may return next year.

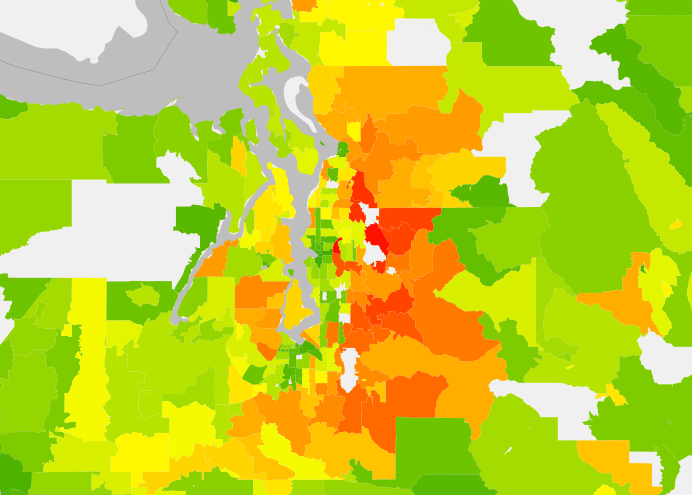

For a fast-growing metropolitan region, a hesitant-to-grow Seattle is a problem. If many more people instead end up living on the outskirts of the region, the data shows their carbon footprints will be much higher due to longer commutes and much more car dependent lifestyles. Road congestion also gets worse, and sprawl is much harder to serve with frequent transit.

By contrast, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu pointed to specific changes making three busy bus routes serving low-income communities fare-free and increasing bus frequencies to serve the surge in riders. She didn’t dwell entirely on process; she talked results, which were overwhelming positive as bus ridership jumped and riders got a monetary boost. Even in America, some mayors are taking strides to catch up to their counterparts aboard when it comes to green urbanism.

The task of decarbonizing cities can seem daunting, but the basics aren’t that complicated. In the Seattle region our power sources already tilt toward green renewable energy, and transportation emissions account for the vast majority of our carbon inventory. (By the way, Sound Transit already contracts 100% of its electricity for light rail from renewable energy.) That means a real solution must focus on transportation and grapple with car dependency.

A few seemingly simple steps can design cities better, and leading mayors are already doing it.

- Design and zone cities so people live closer together and to work, school, and activities, shortening trips and promoting transit use, walking, rolling, and biking.

- Fund and build out connected sidewalks, pedestrian streets, and safe bike lanes that allow people to get around safely and efficiently without a car, reducing deadly crashes to reach “Vision Zero.”

- Speed up transit with dedicated bus lanes and grade-separated rail projects to entice people out of their cars.

- Retrofit and build green buildings, including with heat pumps and air filtration that help filter our air pollution while decreasing energy needs.

- Electrify buses (and expand service) to lower emissions and eliminate diesel pollution impacts along bus routes.

- Electrify freight and right-size freight and emergency vehicles to fit human-scaled streets.

- Electrify remaining vehicles to squeeze out remaining transportation emissions.

Seattle mayors (and other American mayors for that matter) seem to skip steps one to six and start with electric cars. It’s a bit like skipping to dessert. That approach hasn’t been very effective at decreasing emissions or helping people live car-free without putting their lives on the line. Pedestrian deaths are climbing in Seattle and nationwide.

Until Seattle commits to be a walkable, transit-focused city with enough housing for all, climate goals and leadership will elude us.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.