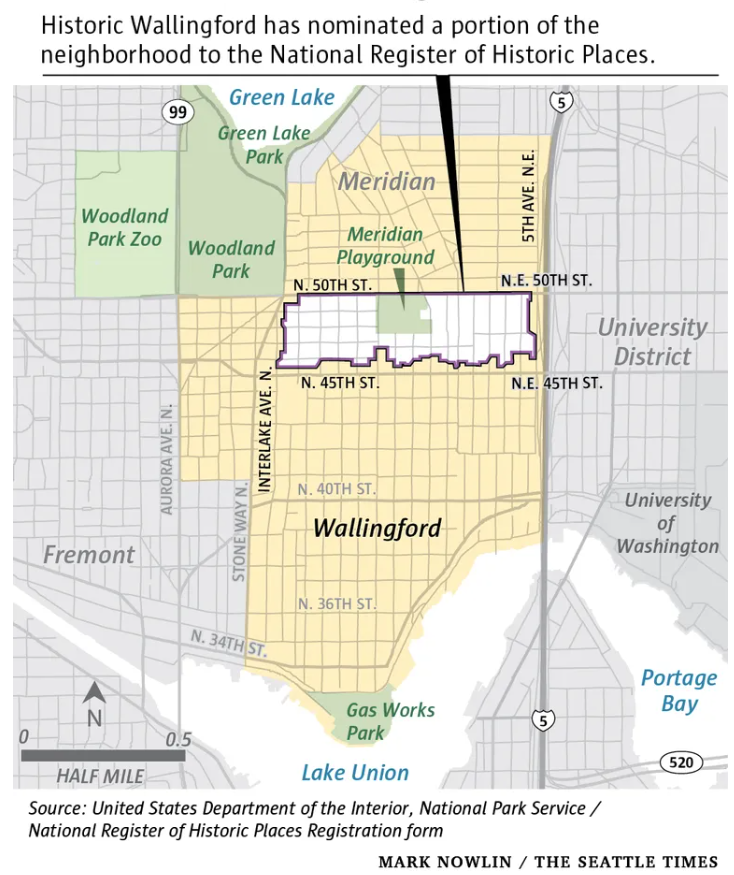

A swath of North Wallingford centered around Meridian Playground received a key approval on Friday that puts it on course to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Critics have warned that the historic district would exacerbate the housing affordability crisis, providing grounds to block zoning changes and new development in the area, as was the case when historic districts were established in Ravenna-Cowen and Mount Baker.

Historic Wallingford, the group that applied for the designation, argued that historic designation would not block development.

“Historic Wallingford is not focused on zoning, and … this historic district initiative is not about zoning,” the group said in a statement. Instead the group argues the designation is intended to document the neighborhood’s history, raise the profile of old homes, promote good architecture and design features, and ensure that new development and older homes co-exist in harmony.

“We argue that without this expanded consciousness, the historic fabric of the neighborhood will slowly unravel as people renovate their property,” Historic Wallingford said.

The Washington Advisory Council on Historic Preservation seemed to agree as it granted approval. State architectural historian Michael Houser said the designation is “totally honorary,” outside of a program that allows property owners to claim a tax credit for rehab work on income-producing properties, such as apartment buildings.

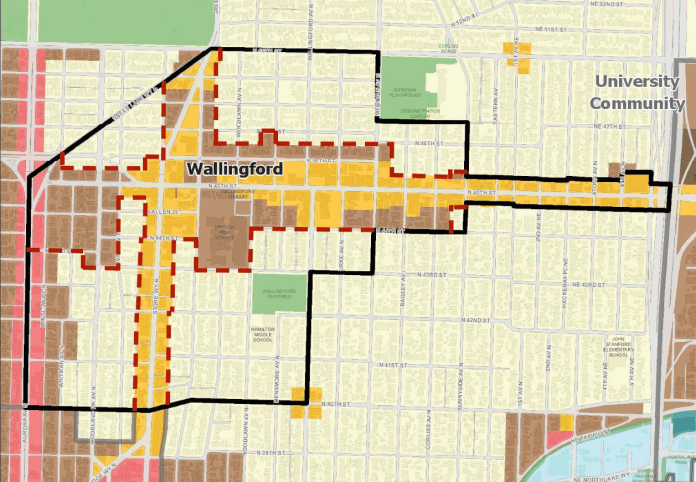

The 2019 Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) rezones, however, ended up carving out the Raven-Cowen Historic District and Mount Baker Historic District from the zoning changes in the remaining sections of the designated “Urban Villages” following lobbying from neighborhood activists. Pro-housing activists worry that neighborhood preservationists will argue this set a precedent as zoning changes are contemplated in newly minted historic districts. Wallingford was a hotbed of opposition to MHA upzones, with the Wallingford Community Council distributing lawn signs and rallying public testimony against the zoning proposal.

Ultimately, the group did not succeed in blocking the MHA program or exempting their neighborhood, but they did squash proposals to broaden the size of the Wallingford Urban Village to cover more of the neighborhood, the bulk of which falls outside the urban village. Even so, roughly half of the proposed historic district falls within the upzoned Urban Village, which snakes along N 45th Street and widens out near Stone Way N.

Despite that history of homeowner activism, most public comment was against the historic designation. There was one significant catch: the state’s process for historic designation only recognizes property owners in the proposed district as having a say in the matter. Most of the commenters against were tenants or had moved out of the neighborhood — some due to the rapidly rising housing prices. Even among property owners commenting, sentiment against designation outnumbered those for the historic district by 20 to 10, Heidi Groover of the Seattle Times reported.

However, the process also assumes those who did not comment are quietly supportive. The proposed historic district encompasses 570 single-family homes, 66 multifamily buildings, and the Good Shepherd Center, which houses a number of nonprofits and is already on the national register. Thus, the voter universe appears to be 636 property owners. Apparently, it would have taken several hundred letters in opposition from property owners to have blocked the proposal. Instead just 30 property owners submitted official letters, a very low turnout vote indeed.

Historic Wallingford has also said it hopes to expand the boundaries of their historic district in the future.

A coalition called Wallingford For All came together to oppose the historic district and fight for housing affordability. They were not convinced by the assurances this wasn’t about zoning and blocking development. A coalition letter garnered hundreds of signatures, including my own and some other familiar names for readers of The Urbanist.

“Wallingford for All will be continuing our work to highlight the state’s investment in this program that touts ‘higher resale values’ and disregards renter voices,” Wallingford For All said in a statement. “We will also be advocating to ensure that this decision stays purely honorary, is not repeated throughout the city, and does not continue the precedent of influencing local land use policies.”

The group didn’t see the effort as a total loss, even as it voiced their frustration at the exclusionary nature of the process and designation.

“We are inspired by the outpouring of support, engagement, and thoughtful letters and testimony by community members who shared their concerns about creating a historic district in Wallingford,” the coalition said. “The state Advisory Council on Historic Preservation acknowledged earlier in the meeting that race and social history should be considered in their discussions. Yet when it came to discussing Wallingford we were disappointed to see no interest in responding to and engaging with points brought up over and over during public comment around Seattle’s exclusionary housing history and downstream policy consequences of this nomination.”

Ironically, one historic element that preservationists highlight about the Craftsman single-family homes they seek to preserve is their function in providing housing affordable to the middle class. That exactly what those homes no longer offer, as most now sell for more than $1 million. For example, 1921 Craftsman in the historic district is listed for $1.44 million, which is fairly typical for the neighborhood. A buyer’s household income would need to be nearly $300,000 to comfortably afford that house.

“The historic district represents a wide range of interpretations of the Craftsman style and the work of multiple builders. The simplicity and artistry of these buildings harmonized into an affordable house design providing style, convenience, and simplicity within the reach of many middle income families,” Historic Wallingford wrote in its application. “The Craftsman style is the first major architectural style movement that originated on the West Coast. California architects Charles and Henry Greene are credited with popularizing the style in the beginning of the 20th century, and it dominated residential architecture from 1905 until the 1930s throughout the country.”

If we were seeking to preserve the function rather than only the form, Wallingford would need to emphasize a different vernacular. Otherwise, the working class will be priced out of the neighborhood. Forms like the Seattle sixplex or courtyard apartments are much more promising on that front.

Urbanist contributor Mike Eliason has suggested that historic districts are the restrictive racial covenants of the 21st century, excluding most Black, Indigenous, people of color from their boundaries by virtue of high housing costs and little new housing. Fellow architect Grace Kim agreed and joined Eliason in opposing the Wallingford historic district. “Whether they believe it or not, it is a racist act,” Kim told the Seattle Times.

Examples of Craftsman architecture abound in Seattle and hardly seem in danger of disappearing off the face of the earth. But if a prevalence of Craftsman is all it takes to get historically listed, many Seattle neighborhoods could clear that bar.

It’s not just the historic designation process that is stacked against tenants and affordable housing advocates. Historic Wallingford received a grant from King County’s cultural funding agency 4Culture to support its operations and funded promotional materials and professional consultants (namely, Northwest Vernacular) to complete the application. Meanwhile, Wallingford For All is a grassroots organization that spun off of Share The Cities with no institutional support.

Still even little resourced as they are, Wallingford For All and their allies will likely seek to hold Historic Wallingford to their pledge that the proposal isn’t about blocking development and zoning changes.

With the greenlight from the state advisory council, Historic Wallingford’s proposal now heads to the National Park Service for a final stamp of approval to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It appears unlikely the park service would turn them down, as this step is considered relatively perfunctory. But it does appear likely more Seattle neighborhoods will follow in these footsteps.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.