As the Seattle City Council gets ready to propose tweaks to Mayor Bruce Harrell’s proposed Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) budget, at the top of the list is traffic safety spending. Not only will this be Mayor Harrell’s first budget, but also the first budget after the deadliest year for traffic violence since 2006 and closely following several high-profile preventable tragedies this year involving people who have been walking and biking.

In 2015 then Mayor Ed Murray announced the City of Seattle’s Vision Zero pledge to end traffic death and serious injuries by 2030, a commitment the State of Washington and several other cities have also made. Unfortunately, traffic deaths have trended up in recent years rather than trending toward zero, casting in doubt the seriousness and effectiveness of the campaign.

It’s a familiar conversation for the budget committee. In last year’s budget, Councilmember Andrew Lewis spearheaded an increase in Seattle’s commercial parking tax that was earmarked for the Vision Zero budget. At the time, this was framed as the only dedicated funding source for the program outside of the funding from Seattle’s 2015 transportation levy.

But commercial parking revenues are not rebounding as quickly as the City had hoped, and that extra Vision Zero money has yet to materialize. Harrell’s proposed 2023 budget actually backfills to the amount that was expected ($2.9 million) mostly using one-time real estate taxes. The budget then adds another $1.36 million, which the administration is saying will be directly used for Rainier Avenue and MLK Jr Way improvements in District 2, in addition to some funding going to NE 130th Street station access.

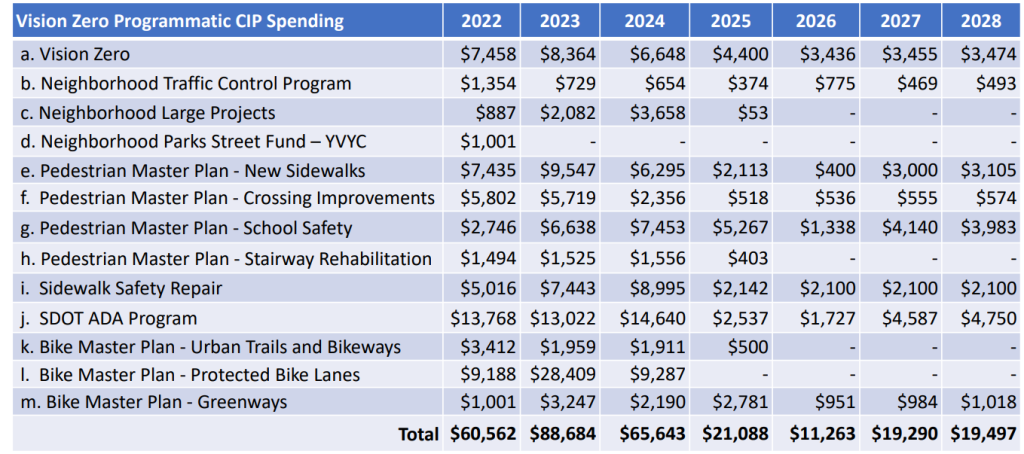

That brings the total 2023 Vision Zero budget to $8.3 million. But that amount doesn’t include all of the programs that directly support citywide safety improvements, like the safe routes to school program, protected bike lanes, new sidewalks, or big projects with safety as a primary project goal. The city council’s central staff compiled a list including most of that spending, and pegs it at $88.6 million. Included are many long-planned projects and spending that was prescribed by the 2015 levy.

Examining just SDOT’s budget doesn’t reveal what policies are being implemented, and how decision-making might be holding costly investments back from being as effective in preventing serious injuries and fatalities as possible.

90-Day review seeks answers

SDOT Director Greg Spotts, in his second month on the job, has instigated a 90-day review of the Vision Zero program within the department. After around $20 million spent since 2015 just from the official Vision Zero budget, the department is taking an internal look at what has actually been effective. And there are encouraging signs.

In an op-ed on traffic safety recently in the Seattle Times, Spotts suggests a substantial change has been made inside the department already. “At the kickoff meeting of this new cross-departmental effort, one of our senior leaders asked me, ‘When will the department have the license to prioritize enhancing safety over other concerns in operating Seattle’s street system?’,” he wrote. “And I told him, ‘Today. Now. Go and do it.'”

Time will tell if that means projects like the repaving of 15th Avenue NW are rethought to actually embed Vision Zero principles. Or if the City has a Harrell-administration version of 35th Avenue NE, where the prior mayor’s office forced changes to a fully designed SDOT project and caused the department to have to come up with justifications after the fact.

Until those decision-making changes show results, the city council looks poised to debate the correct path forward in one of the only avenues available to them: the budget.

An emergency response for Vision Zero?

Councilmember Tammy Morales, whose district in Southeast Seattle continues to see a hugely disproportionate share of all traffic crashes in the city, said she was glad to see somewhat of an increase in the Vision Zero budget for 2023. But she also made it clear that she did not think that the city was going far enough.

“I think, just by way of comparison, we spent $108 million dollars repairing the West Seattle bridge — relatively quickly — and that’s something that moves cars and trucks, but there’s no sidewalks, there’s no bicycle infrastructure on that bridge and I would like to see us invest in a similar way in the urgency of making sure that the infrastructure that we need to keep people safe on our streets, in our neighborhoods, through areas like SoDo where there’s not just freight traffic but pedestrians accessing services and just trying to use the area as a neighborhoods. We need to have a similar sense of urgency to get those things fixed as well.”

On the other hand, Councilmember Alex Pedersen, transportation committee chair, said that transportation funding appeared to be “lopsided” toward protected bike lane projects, citing a 147% increase for the bike lane budget next year compared to a 34% increase for pedestrian projects. He suggested that this didn’t match where the investments were needed, noting that since 2015 a majority of people who have lost their lives in Seattle have been pedestrians.

In fact, the spending on protected bike lanes planned for next year is due to a number of projects that have been in the pipeline for many years coming to fruition all at once: MLK Jr Way, Beacon Hill, and the Georgetown to South Park Trail are all set to see substantial progress next year if not full completion. Work is ramping up on a number of other projects to get the department closer to the goal promised to voters seven years ago around miles of bike facilities, including the Georgetown to SoDo route and the missing connection along Alaskan Way. And those projects will likely have a positive impact on pedestrian safety as well, by adding traffic calming and protective signals in most cases.

Council President Debora Juarez brought up the funding that the Washington State Legislature allocated this year for improvements along one stretch of Aurora Avenue N. Juarez expressed gratitude to the legislature, especially State Senator Reuven Carlyle, but noted there will be more work to do on the entire eight-mile corridor.

Her comments came the same week that SDOT issued a Request for Qualifications for a consultant on its corridor-wide study of Aurora: the department will spend the next year working with that consultant to develop a full report and likely spend additional time on top of that getting it to full design. In the meantime, people will be hurt, many seriously, and some will die on what is consistently one of the deadliest roads in the state. The same week as the city budget was introduced, a woman using a wheelchair on Aurora near 98th Street was killed by a driver. That crash was one of approximately 10 injury crashes in just a week. It remains to be seen whether perpetual consultant reports and similar institutional roadblocks will be included in Director Spotts’ 90-day review.

Center City Streetcar Frustrations

The budget for Vision Zero projects was not the only thing that councilmembers debated during their first pass at SDOT’s budget last week. Another issue that prompted responses from across the entire council was the Center City Connector. Mayor Harrell has proposed yet another study around the future of the streetcar along First Avenue, with the Office of Economic Development taking the lead on looking at the overall subject of mobility downtown. During the budget hearing, SDOT’s Finance Director Kris Castleman directly connected the scope of the study to other work that the city is doing around the future of Third Avenue. This new study comes one year after the Durkan Administration, which had halted the project in 2018, proposed spending 2022 getting the Center City Connector up to date on cost estimates and possible financing, given that some grant awards had expired and construction cost escalations have driven up the project budget.

Many councilmembers expressed their frustration with how slowly the project is moving. “My entire time in office this project has now been delayed because of the previous administration,” Budget Chair Teresa Mosqueda, first elected in 2017, noted.

“I feel like, as it relates to the streetcar project, we’re kind of moving the goal posts on getting that done by including it in [the downtown mobility] study,” Councilmember Tammy Morales said during the budget meeting. “This project has been in the works for quite some time. I’m interested to understand why a financial operating plan has not been completed and how we complete that plan so that we can answer these questions and move on.”

Councilmember Andrew Lewis echoed their frustration. “I don’t want us to be here a year from now, and the study never happened and it never went out to bid, because there was disagreement between the different departments on how to do it, and the executive [Mayor Harrell] comes back to us to say ‘oh, you know what, it really would have made much more sense for this with SDOT or with whatever, and then we lose a year of progress in this really critical work.” Of course, that’s where the city has been at on this streetcar project for quite some time.

But it’s fairly unlikely this budget season will be the time councilmembers are able to make any headway on advancing the dormant streetcar project. At this point, it is almost certain that the intense pressure on the city’s general fund will push streetcar funding to a future year.

The bulk of the time spent debating Mayor Harrell’s 2023 budget will likely not be spent on the transportation budget. But in the coming weeks we’ll see councilmembers from across the dais make their priorities known, and we’ll begin to see what small tweaks the body makes to the mayor’s fairly stay-the-course budget.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.