Many neighborhoods were left out and many unsafe, unhealthy streets remain.

Ever since Mayor Jenny Durkan announced in 2020 that 20 miles of the pandemic-created Stay Healthy Streets would become permanent, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has been figuring out where that permanent infrastructure will be, what it will look like, and how to pay for it. Stay Healthy Streets are neighborhood streets where residents were encouraged to walk, bike, or roll in the roadway with the help of “Street Closed” signs and diverters, and they have been added to residential districts in the four corners of the city. But making them all permanent was a commitment the city intentionally did not make.

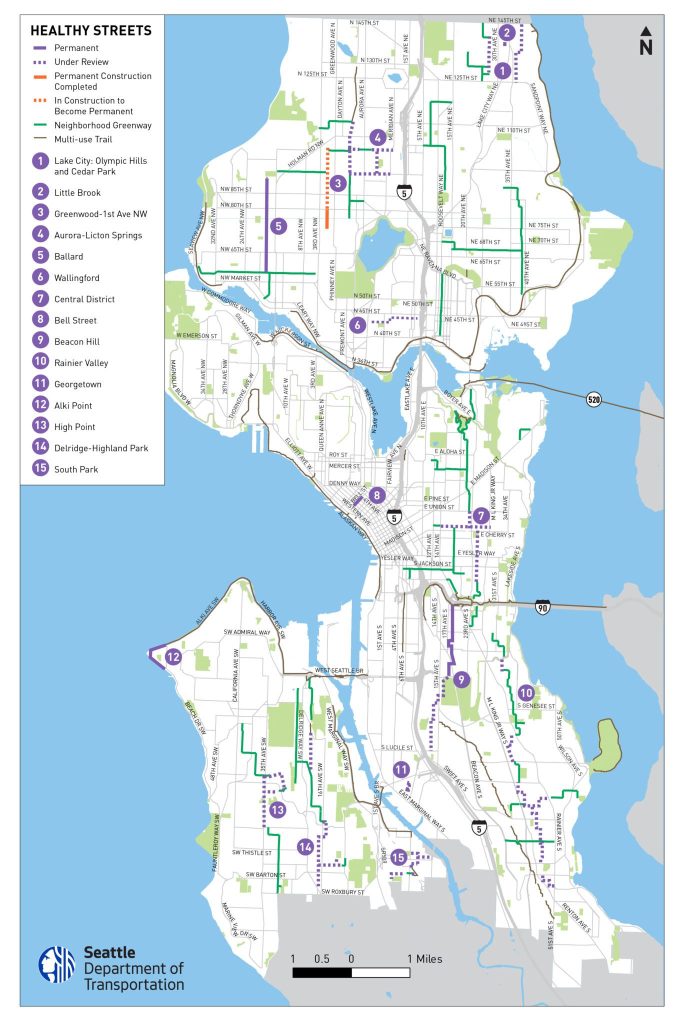

This week, SDOT released a new map of the proposed “Healthy Street” network that outlines some segments of that permanent network, confirms which segments are not under consideration for permanent infrastructure, and notes that large segments of the Healthy Street network are still “under review.”

“At each location, there may be a combination of permanent Healthy Streets, neighborhood greenways, and/or areas for further review and outreach.” SDOT’s blog post accompanying the new map noted. “Over the next few weeks, we plan to visit all existing Healthy Street locations to check on the condition of signs and repair or replace them as needed. We’ll also remove signs on Healthy Streets that will become neighborhood greenways like they were before the pandemic. Over time, we’ll begin installing the updated signs for permanent Healthy Streets locations.”

The map confirms that Ballard, north Beacon Hill, and Belltown will see permanent Healthy Street infrastructure in addition to Greenwood, where the first set of permanent infrastructure has already been installed. It also spells out how major sections of the Rainier Valley Stay Healthy Street, along with segments of the Central District, Aurora-Licton, and High Point-Delridge Stay Healthy Streets, will revert to a standard neighborhood greenway, without the “street closed” signs.

The rollout of permanent infrastructure along these routes has been slower than expected. In early 2021, the department appeared poised to quickly make the transition to permanent infrastructure by mid-year, even as it was hesitant to fully commit to specific designs in every neighborhood. In Greenwood, the only neighborhood where changes have been made yet, SDOT held several meetings, some fairly contentious, before moving forward with the paint-and-planters design that appears on streets today and looks poised to become standard infrastructure.

But the decision to only move forward with 20 miles of permanent Healthy Streets is set to create a two-tiered neighborhood bikeway network, where the old standard greenway infrastructure just isn’t even meeting the baseline expectations for users.

The map of planned Healthy Streets across the city provides another reminder that the densest neighborhoods, the urban centers of Downtown, Capitol Hill, First Hill, the U District, and Northgate were all largely left out of SDOT’s broadest pandemic open streets program, with currently no plans to expand these public space programs to those neighborhoods. Council District 7, including Queen Anne and Magnolia, is essentially excluded from the map as well. Thus, the Healthy Street network leaves out a pretty large, and highly populated, section of the city.

Alki Point also getting a Healthy Street

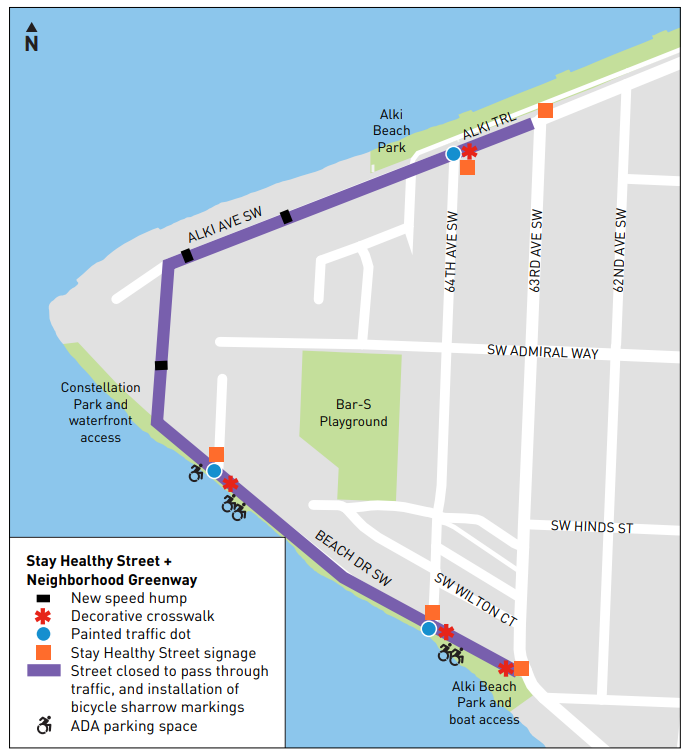

SDOT also announced this week that it had selected a potential design to move forward for its Alki Point open street in West Seattle. Originally branded a “Keep Moving Street” along with now long-gone Golden Gardens Drive in Ballard, a widely completed survey asked respondents which alternative they might prefer for the street, with some other possibilities that included creating a wider sidewalk along Beach Drive SW or making the street one-way for vehicles.

The design moving forward, which was the favorite among survey takers by just a hair, would essentially install the same infrastructure on most other Healthy Streets: speed cushions, “street closed” signs, and added stop signs for cross traffic.

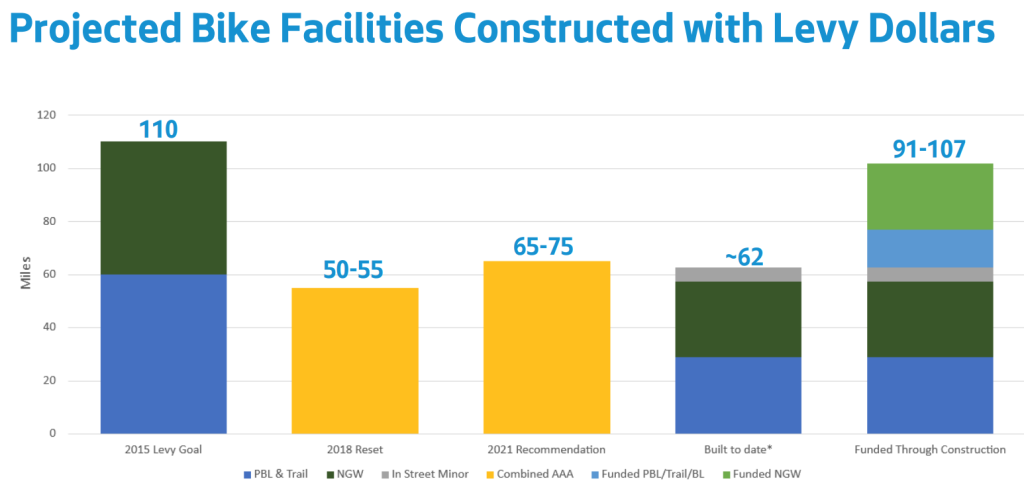

As these citywide changes happen, SDOT’s Project Development Director Jim Curtin told the committee overseeing the Move Seattle levy this week that the department is now planning to consider permanent Healthy Streets as contributing to its 2015 goal to build 60 miles of neighborhood greenways across the city. Paired with new paint-only bike lanes, which also had not previously counted toward the overall levy goals, SDOT now says that it is on track to build up to 107 out of the 110 miles of bike facilities promised in the levy. This goalpost-moving may placate a small number of stakeholders, but doesn’t necessarily persuade voters counting on bike improvements that the promises made have actually been kept.

SDOT is planning to add some new neighborhood greenways in the next few years, using funds from school zone safety cameras that ticket speeding drivers outside a number of Seattle schools. But now, on top of the fact that much of the greenway network doesn’t connect and doesn’t provide great connections across busy arterials, there is now a new set of tiers for riders to understand — Healthy Streets or regular greenways.

In short, it’s still not clear that the neighborhood greenway network is achieving what was envisioned when Seattle started adding them to its streets.

Healthy Streets represent a response to pressure to rethink how public space was used during the height of the pandemic. But as the program evolves and essentially winds down, and those pressures become less and less visible, Seattle may already have outgrown them.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.