The work to modify roads in Washington State to make them accessible to people who walk or bike is an enormous undertaking. Most cities and counties are significantly lacking in the resources needed to make those streets safer and more attractive to people who walk and bike. This includes the 1,685 miles of state highways that run through population centers, of which 542 miles lack sidewalks and 1,142 miles lack bike facilities.

Thanks to added funding from this spring’s Move Ahead Washington transportation package, two of the state’s most coveted grant programs, the Bicycle and Pedestrian grant program and the Safe Routes to School grant program, have essentially doubled in size. With around $100 million in grant funding available during this two-year cycle, the number of applicants has also jumped, with the total amount requested across the state coming in at $457 million, more than twice the amount requested during the last cycle in 2020. But there was a noticeable entity largely missing from the large flood of applications submitted this year: WSDOT itself.

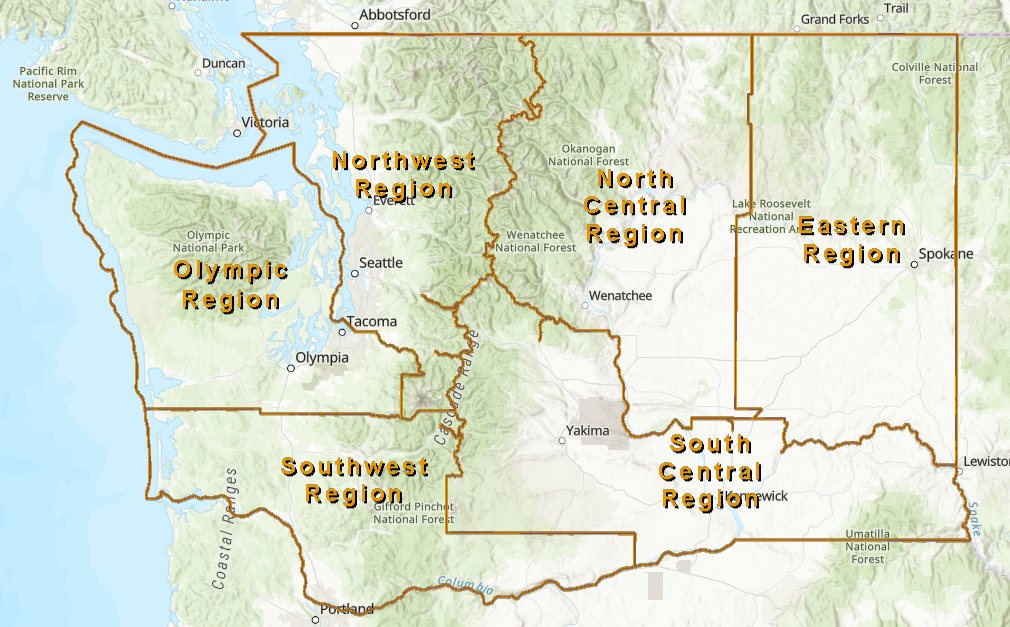

Among the 2022 grant applications, only one regional WSDOT office, out of the six in the state, submitted any project applications in either the Safe Routes to School or Bicycle and Pedestrian grant programs. While that means that cities and counties in Washington are not competing against their own state highway department for a relatively scarce pool of dollars, it also means that if those cities and counties want to see improvements to the state highways that bisect their neighborhoods, they have to be the ones to step up and ask for funding. Out of the 148 applications for Bicycle and Pedestrian grants, a large proportion of them dealt with areas at or along state routes.

With these biennial grant programs set to be one of the primary ways that the state legislature improves existing facilities for multimodal travel, the level of involvement that WSDOT regional offices have in these grant programs will determine how impactful they are in improving conditions on some of the state’s most deadly roadways.

WSDOT’s own 2020 Active Transportation plan lays out the challenges inherent in making its state highway network safer for people walking and biking.

“The findings of the analysis — that state routes in many locations need improvements to be suitable for walking and bicycling — are not a surprise since state highways were not originally designed or constructed for the purpose of providing safe active transportation connections,” it noted. “Given rapid growth along and around highways, hundreds of miles of state routes now function as primary community streets with associated needs for design suitable to local short trips. State law directs WSDOT to ‘balance system safety and convenience…to accommodate all users of the transportation system.'”

But funding to create more balance on those roadways is scarce, with most state highway dollars going toward expanded capacity or routine maintenance. With the Move Ahead Washington transportation package, lawmakers did change state law to require the highway agency to evaluate, and potentially add, missing bike and pedestrian facilities when they do that maintenance. Urgent safety needs, however, often do not coincide with the agency’s maintenance schedule, particularly with maintenance still underfunded in comparison to flush expansion dollars.

The lack of safe infrastructure for walking and biking on these streets comes at a cost. Between 2010 and 2019, 27% of serious injuries and fatalities due to traffic crashes occurred on state highway routes, despite those state highways only accounting for nine percent of the state roadway network. According to a 2009 study, Washington has 180 communities, of different population sizes, where a state highway functions as the primary main street. Since state highways tend to have the highest speed limits in an area, with only 6% of state routes signed at 25 miles per hour or less, the urgency to make these places safer for active transportation is real.

When the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) submitted an application to improve safety on the NE 45th Street overpass at I-5 by installing pedestrian fencing and a higher railing, the WSDOT Northwest region office supported the proposed changes, a position that came after vetoing a more robust safety proposal that would have potentially impacted vehicle traffic. However, the agency also told SDOT that they didn’t have the resources to lead on any design changes, which led to SDOT needing to provide spare capacity in order to keep the proposal on track.

Unlike SDOT, many departments of transportation in smaller cities and towns in Washington likely won’t have this ability. As of last year, 55% of cities and towns in Washington had never applied for a single one of these grants since the program launched in 2005.

In a report on the bike and pedestrian grant programs published last year, WSDOT itself acknowledged that the applications for improvements along state highways represented a big opportunity for the agency, noting that “local partners submit applications in each cycle for projects on state highways that often rank high on safety needs. These applications demonstrate that local partners prioritize these projects over those on their local streets, highlighting the role a state highway can play in a local walk/bike network, either as a critical connection, as the only route available, or as a barrier to mobility. It also points to the importance of aligning local, regional, and state plans and projects so WSDOT can incorporate needed improvements into future programs and projects as possible.”

The Urbanist contacted the WSDOT Northwest region office, responsible for most of the Puget Sound area, about the lack of applications this year despite unprecedented funding.

“The greatest factor in our lack of submissions this year has been staffing,” WSDOT NW regional office spokesperson Krista Carlson said. “Over the past few months, we’ve had several key staff retire or seek alternate employment. Although we’re working to fill these vacancies quickly it can be difficult. At any given time, our region has between 150 and 200 positions to fill, and sometimes institutional knowledge, as well as programmatic and service gaps occur from the time an incumbent leaves until a new replacement is found. While this season was a miss for us, we fully expect to be more involved the next time these grants are offered. Our work for safety continues through activities such as the changes to the Rainier Avenue/I-90 ramp junctions that we funded with our own traffic operations funds.”

As for the one WSDOT regional office that did submit applications, the Olympic office, it may be an example of the type of collaboration that should ideally be happening statewide.

“The four applications from Olympic region came from discussions about existing projects and already identified needs in these vicinities,” Stephanie Randolph, a spokesperson for the Olympic Region office wrote in a statement. “In these cases, we were working on nearby projects or collaborating with a different lead agency on their project. We saw gaps that we could fill with this grant opportunity.”

Three of the project applications submitted by Olympic Region would improve segments of SR 99, one of the deadliest highways in the state, with a fourth project impacting SR 7 south of Tacoma, through an area that includes multiple different jurisdictions.

It’s clear that the near-complete lack of applications should raise concerns, particularly for future cycles. But even at full steam, the state would likely continue to see a vast majority of applications submitted by cities and counties.

“The primary intention of WSDOT’s Bike and Pedestrian/Safe Routes to School grant program is to support safety enhancements at the local level,” NW Region’s Krista Carlson said. “When a WSDOT Region office applies it will be in partnership with local agencies that identify a change on the state system as a high priority to complete and connect the local network and where WSDOT is the appropriate agency to lead the work. In a larger city such as Seattle, the city is the right agency to apply for funding to change the state route where they manage it, such as with Seattle DOT’s application for work on SR 99/Aurora Avenue North that was funded. WSDOT is a partner, not a competitor. The Northwest Region includes several larger cities within the urban/suburban areas.”

In Washington cities with populations under 25,000, WSDOT holds more responsibility over the operation of state highways. But in all cases, staff capacity at the local level is a consistent barrier to forward progress. By way of the state traffic safety commission, funding has been earmarked to expand capacity to apply for these grants themselves, but this is a very circuitous and inequitable way of funding improvements to state highways that have a clear and present need.

The barriers to making improvements along some of the highest opportunity streets in Washington illustrate the institutional problems that have prevented the state from making much progress on its statewide Target Zero commitment to eliminate serious injuries and fatalities in traffic, a goal that has been in place for over two decades. Despite added funding, bureaucracy could continue hinder progress. It may take an institutional shift to really make the difference.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.