Seattle’s long nightmare is over. Nine-hundred and nine days after the West Seattle Bridge was closed out of an abundance of caution around its structural integrity, it reopened Sunday without much fanfare. One moment a superstructure that once carried around 100,000 vehicles on an average weekday had closed, and seemingly just as quickly, it was open again.

As traffic patterns start to look like some version of “normal,” many people would prefer to put the entire episode behind them. But the West Seattle Bridge emergency will undoubtedly leave a lasting legacy on the city and the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT). If we’re lucky, it will be a demonstration that swift action is possible and lead us to take steps to improve walking, rolling, biking, and transit infrastructure by mobilizing City resources in a similarly concerted fashion. But will smaller-scale multimodal projects have the same cachet as an ailing megabridge?

Reconnect West Seattle: making up for lost time

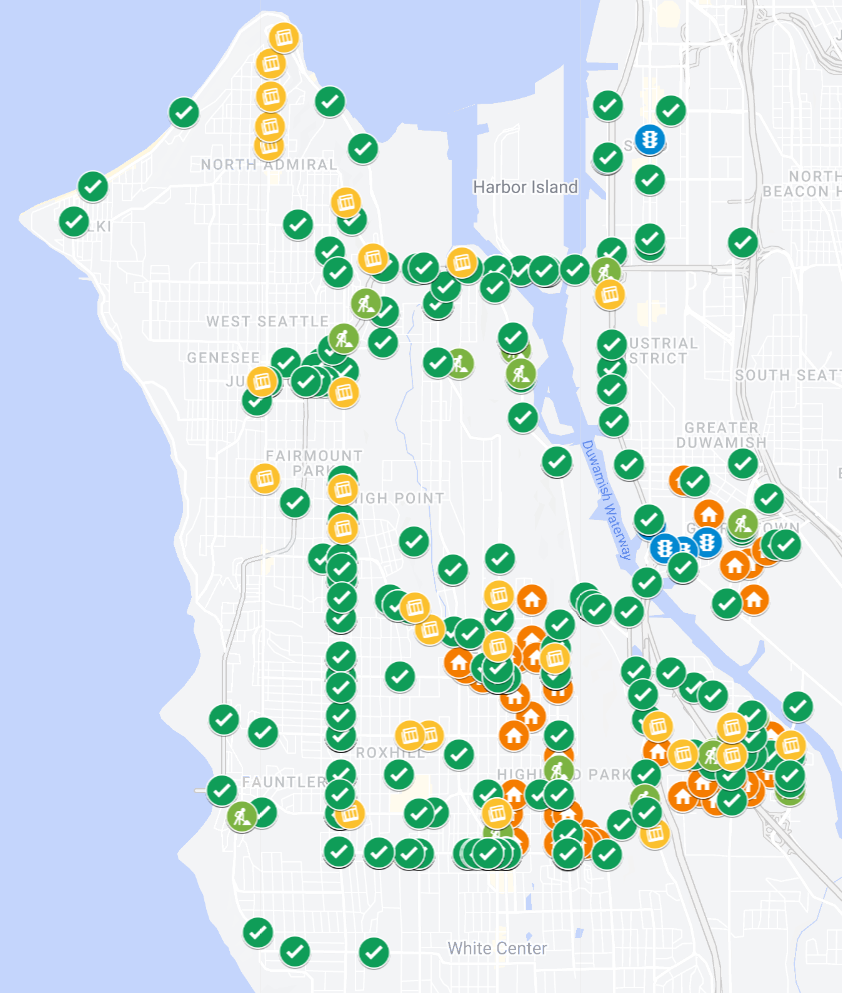

The repair of the West Seattle Bridge wasn’t the only component of the bridge emergency SDOT mobilized in response to the crisis. Seventy other projects, collectively called the Reconnect West Seattle projects, were planned by the department to adapt the southwest quadrant of the city to the reality of two-and-a-half years without the high bridge. To date, nearly 60 of them are already complete.

Many of these projects were directly related to traffic diversions that brought unprecedented volumes of traffic through neighborhoods and involved adjustments to traffic lights and repaving of streets that carried that traffic. But other projects were ones that should have been done or planned for already to make it easier for people to take transit, walk, and bike, in alignment with the city’s adopted goals.

This was particularly true in the Duwamish Valley, where many drivers found themselves diverted through. The City had no plans to add a neighborhood greenway in Georgetown until the Reconnect Seattle program moved one forward as part of a new Home Zone, an SDOT program that provides traffic calming and pedestrian improvements. The same is true for South Park and Highland Park. New walkways to bus stops, missing curb ramps, and repaired sidewalks represent investments that probably should have happened regardless of the bridge emergency. The fact that they might not have happened without it should be cause for introspection at the agency.

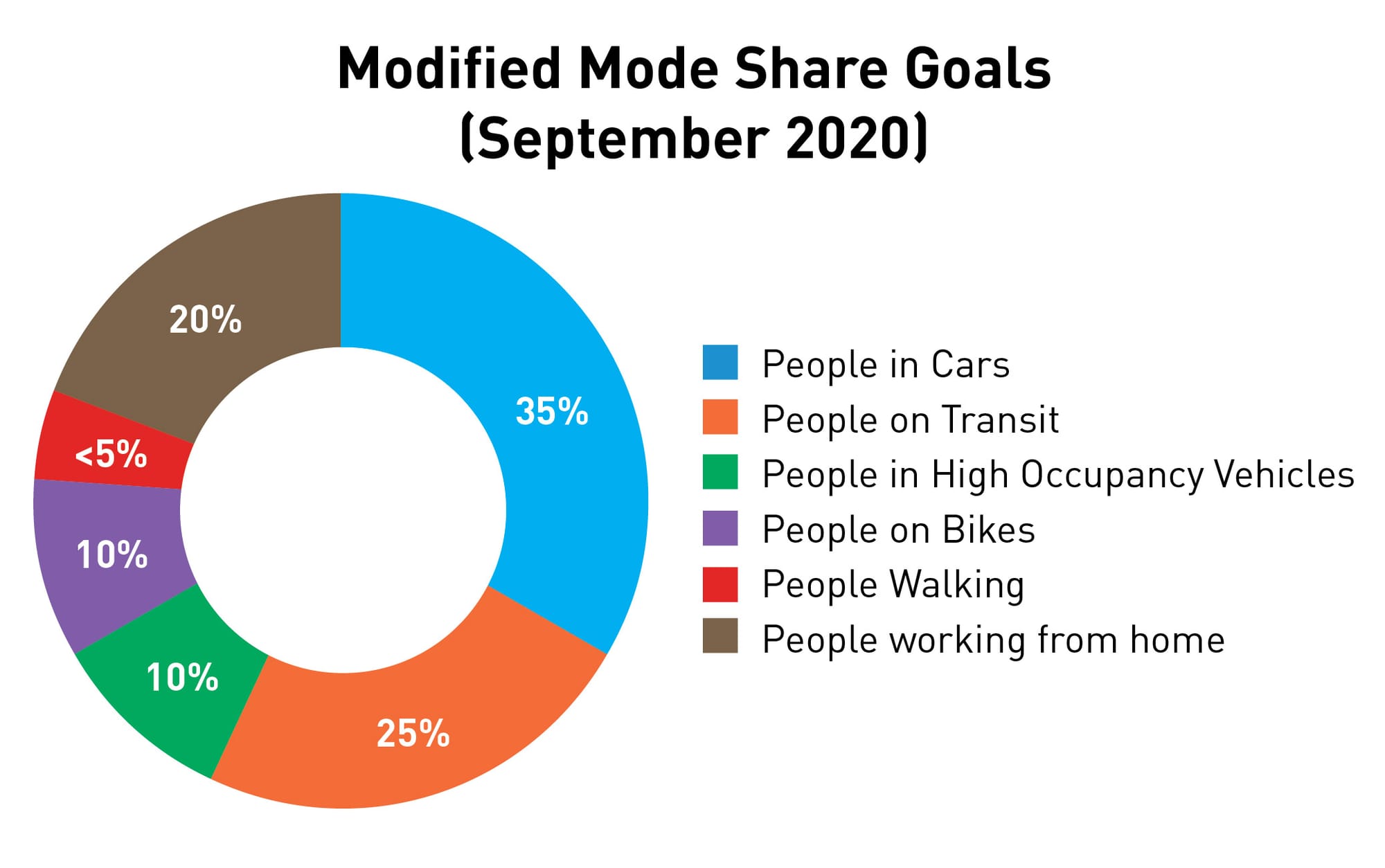

Aided by an electric bike boom, biking did grow in popularity in West Seattle, but it’s not clear if it was enough for the City to make its 10% mode share goal. More work remains to make biking a safe and attractive option on the peninsula and citywide.

But the constellation of Reconnect West Seattle projects represent the type of response that will be needed moving forward: rapidly implementing quick-build changes over wide swaths of the city in a brief period of time without belaboring public input and outreach phases, which have often grown to be agonizingly slow in Seattle. It’s something that is needed right now to actually meet the scale of the traffic safety crisis impacting Washington State and the U.S. at large. It’s something that has been needed ever since Seattle adopted its Climate Action Plan and pledged to reduce total vehicle miles travelled by a substantial amount by 2030 to meet emission reduction goals. And it’s something that will be needed even more in the future, as heat waves and other severe weather events intensify and the city needs to adapt, everywhere, all at once.

The West Seattle Bridge closure was a trial run, and the best thing that can happen now is for SDOT to utilize the skills learned and apply them to what’s to come. But a pivotal piece of being able to do that will be having the trust of the public.

The issue of public trust

A seismic event like the closure of the city’s busiest non-state highway forced SDOT and its daily work into the lives of many residents in a way it likely hadn’t been present before. As the comment section of the West Seattle Blog can attest to, this new level of engagement provoked a lot of strong feelings about how competent the agency appeared to be. As the details around how it occurred were made known in the months that followed the closure, exactly who was responsible took a back seat to whether or not the department was really doing all it could to get its connectivity restored. A months-long process leading up to former Mayor Jenny Durkan deciding that the bridge should be repaired and not replaced didn’t exactly represent incisive action to a lot of people.

But within SDOT, there is every indication that every part of the department that could be mobilized to move the repair of the West Seattle Bridge was mobilized. Even though the repair officially didn’t start until fall of 2021, work stabilizing the bridge and designing that repair has been ongoing since it closed. The City came close to meeting its mid-2022 goal for reopening the bridge, though facing a four-month concrete stoppage earlier this year that delayed work. And so there remains a gulf between the inside and outside perceptions of the agency, a gulf that is likely demoralizing and frustrating for a lot of public employees doing their best to promote SDOT’s vision and values.

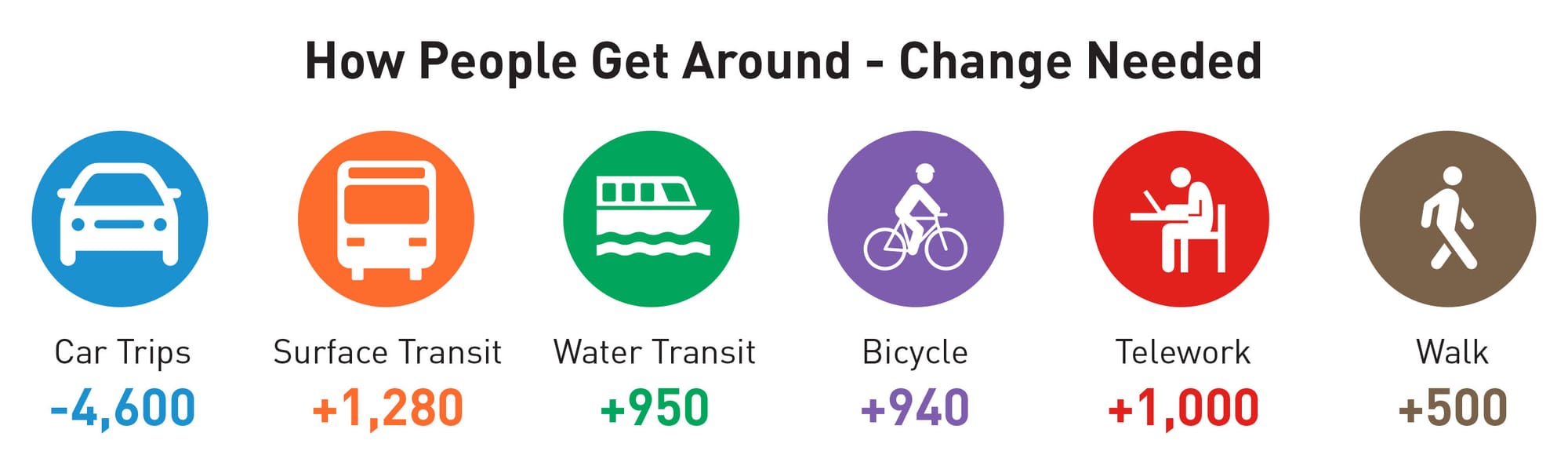

Then-SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe put Heather Marx in charge of the response to the West Seattle Bridge closure after being SDOT’s director of downtown mobility and getting SDOT through the closure of the Alaskan Way Viaduct. Early in the emergency, Marx explained the agency’s goal of raising West Seattleites’ transit usage from its 17% mark pre-pandemic to 25% in order to grapple with the lost capacity of the bridge. It doesn’t appear that goal was achieved as transit was slow to rebound citywide in the pandemic era, which was more prolonged than leaders hoped in 2020. But measures like making the Spokane Street low bridge transit and freight only did help maintain connectivity to the rest of the city, promoting transit use along the way. With the bridge open, SDOT removed the transit only lane restrictions and deactivated the cameras that enforced them.

At an event on the deck of the West Seattle bridge earlier this month, I asked Marx what she hopes the long-term legacy of the bridge closure will be.

“I hope that the long term legacy for folks is that they understand that there are more ways to get off the peninsula than in just your single-occupant car,” Marx said. “I also hope that by being transparent every step of the way, and keeping our promises within the bounds of possibility, that we build some trust with the community about SDOT’s ability to do big things.”

The Move Seattle levy’s “reset” and the politicization of safe biking facilities on 35th Avenue NE in recent years have also not served to bolster the public’s confidence in SDOT, even as the blame for those events can be largely traced to forces outside the department entirely. Perhaps for a city department of transportation in charge of as many different projects and trying to please as many different constituencies as SDOT is, fully regaining the public’s trust just isn’t possible. If it could be done with any one thing, fixing a bridge might be it.

I also asked SDOT’s incoming director Greg Spotts, who hasn’t even been sworn into his job, about this gulf in public confidence.

“I’m sure that folks will find me that want to have that conversation, and… to the extent there’s lessons to be learned, and there must be some, from mobilizing to deal with a near-catastrophic event, and how the public sector — which moves very slow — can react, I’d love to figure out what lessons we can learn,” Spotts said.

The shadow of the West Seattle Bridge closure will surely loom over Spotts’ tenure and shape the department for years to come, in mostly invisible ways. The best we can hope for is that the virtues of SDOT’s response, and what was learned from it, will be enough to outweigh the setbacks.