Back in May 2017, the City Council of Tacoma declared a public health emergency related to homeless encampments. The following month, the Council passed a resolution allowing for the creation of temporary shelters throughout the city to get people off the streets and protect them and communities from health risks associated with encampments. Currently, nine shelters exist in Tacoma and are funded by the City, including six run by the City and three operated by faith-based organizations.

As of January 2022, Pierce County Human Services counted 1851 individuals experiencing homelessness in the city as part of its Point-in-Time Count (PIT). This number represented an increase of over 800 people from the previous year. About 700 of these individuals were on the streets or their whereabouts unknown. However, it is well known, and Pierce County admits this, that there are limits to these types of population counts, and that the true number of those struggling with homelessness is likely much, much higher. Anyone traveling through Tacoma can easily find a litany of tents and makeshift shelters near many major thoroughfares.

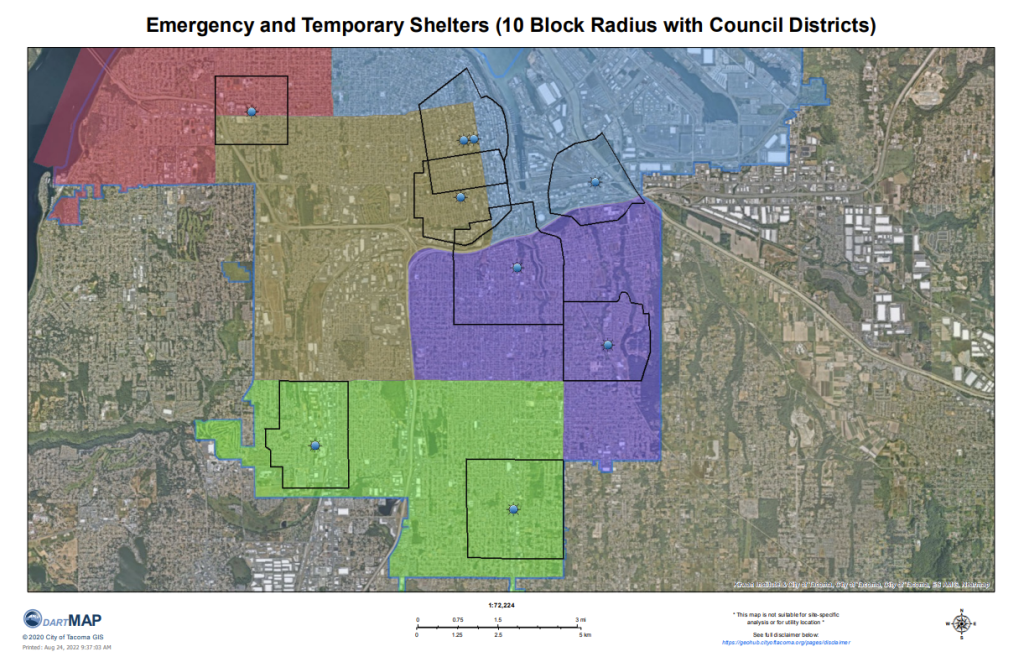

More recently, on September 7th, City Council announced that District 1 Councilmember John Hines would sponsor a new ordinance that prevents encampments in a 10-block buffer zone near these temporary shelters. Councilmembers Joe Bushnell and Sarah Rumbaugh are also co-sponsors of the ordinance. This ordinance is a response to community outrage regarding safety and health concerns related to unsanctioned encampments. The ordinance was set to be introduced by Councilmember Hines at the Council meeting on September 13th, but it was quietly removed from the agenda before the meeting, likely due to pushback from local mutual aid organizations.

The ordinance’s memo cites a U.S. Department of Justice report that states: “evidence from police case studies shows areas adjacent to transient encampments have higher levels of petty and serious crime unrelated to “routine behaviors,” such as drug dealing and usage, disturbance, theft, prowling, burglary, panhandling, fighting, vandalism, armed robbery, rape, and aggravated assault” in addition to sanitation issues.

Of course, these characteristics lead to an area being perceived as dirty and unsafe, increasing frustration from nearby residents and businesses. That being said, this DOJ report is based off of police data, which often underestimates racial bias.

A “safe” zone?

The 10-block buffer would aim to address all of this. First, according to proponents, it would aspire to create a “safe zone” for those living in the shelters from behaviors that may have led them to homelessness in the first place. Those that are struggling with homelessness are easy targets for criminals and violent offenders. Temptations, negative influences, and threats to safety would be mitigated to help them on their road to recovery. Second, communities with shelters would have their images cleaned up while those without shelters may be more open to hosting shelters themselves once they see the benefits. Finally, the sites may be able to better operate as they will deal with fewer off-site issues.

Anyone violating this safe zone will be swept like any other unsanctioned encampment while being offered assistance, presumably at the nearby shelter if beds are available and the people being swept accept the shelter’s policies.

Los Angeles passed a similar ban just last month preventing encampments within 500 feet of schools and daycare centers. Local homelessness advocates pushed back, stating that these types of bans only serve to further displace people and make it more difficult for outreach staff to establish trust again. That is true, a buffer zone further criminalizes not having the resources to own or rent a home, and will likely be the case here as well. But in Tacoma’s potential scenario, there would be a nearby shelter with resources that someone can choose to go to.

In the above memo, the City states that outreach teams made contact with 66 different individuals in July 2022, with only 12 accepted offers of assistance. Buffer zones could negatively impact these already abysmal numbers.

Rising complaints are costly and may be counterproductive

Emergency call data is used to emphasize the impact of encampments on communities and is the main argument for buffer zones. Let’s examine it.

For an encampment previously at the Tacoma campus of The Evergreen State College, there were over 600 calls (both 9-1-1 and 3-1-1) to South Sound 9-1-1 in the months leading up to a sweep. Following the sweep, this number dropped to close to 450 calls. It is not indicated how many calls before the sweep were even related to the encampment, just that they were made in the proximity of it. Though it is noted that Mental Health, Welfare and Homelessness were identified as the main categories of calls.

This is a significant reduction in the number of calls, but it should be made clear that not all emergency calls are actually emergencies. A report published by the Vera Institute of Justice found that across most U.S. cities, less than 3% of emergency calls are violent in nature. One of the cities mentioned in the report is Seattle, with about 7% of its calls being violent and the remaining being spread across traffic, property, non criminal, mental health and other concerns. One could expect similar numbers for Tacoma. Thus, it may be misleading to use emergency call data to justify further sweeps and buffer zones.

Of course all of these calls will expend city resources, regardless of their validity, but it may be unfair to make these encampments the scapegoats when many houseless individuals are just trying to get by. In other words, while these encampments may not be the safest, they may be the best people can do when they have no resources or other access to shelter. Homeowning community members claim to be concerned for these houseless people, but their complaints speak louder: the memo states that 22% complaints to Tacoma City Council since January 2022 were related to unsanctioned encampments.

Tacoma is not the only city to experience a rise in public complaints related to homelessness. In a report published by the Urban Institute’s Housing Matters Initiative, between 2011 and 2017, San Francisco’s homeless population grew by only 8% but overall 911 and 311 calls grew by 72% and 781%, respectively. An extremely disproportionate increase.

Less than 1% of these calls resulted in arrests, with 10% resulting in citations and 89% resulting in move along orders that shift the problem to another location for the cycle to repeat. This type of policing that serves citizen calls only serves to widen the divide between people who are housed and people who are not while not addressing the root issues.

Good shelters exist, but more are needed

Tacoma’s creation of these temporary shelters has offered a significant improvement in support for unhouse people over previous methods that focused on their removal from public spaces. At a minimum, these shelters include fencing, hand washing stations, garbage services, bathroom facilities, electricity and potable water.

The nine shelters include:

- The Stability Site – 1421 Puyallup Avenue

- The Tacoma Emergency Micro-Shelter (TEMS) Site #3 – 602 N. Orchard Street

- The Tacoma Emergency Micro-Shelter (TEMS) Site #4 – S. 69th Street and Proctor Street

- The Mitigation Site – S. 82nd Street and Pacific Avenue

- The RISE Center Emergency Stabilization Shelter – 2139 Martin Luther King Jr. Way

- The Mitigation Site – 3561 Pacific Avenue

- Altheimer Memorial Church of God in Christ – 1121 S. Altheimer Street

- Bethlehem Baptist Church – 4818 Portland Avenue East

- Shiloh Baptist Church – 1211 S. I Street

The shelters fall under three categories: Micro-Shelter Sites, Enhanced Shelters and Emergency Mitigation Sites. The first category is another name for tiny home villages, the second could be a tiny home village or a building converted to a shelter and the last is authorized tent encampments on city property.

The City states that both micro-shelter sites and enhanced shelters will be guaranteed supportive resources like case management and employment assistance. Furthermore, most sites have 24/7 on-site management and fencing. Specific amenities vary from site to site, with some offering showers, communal kitchens, additional counseling, food programs and even security services. All of this together shows a multi-faceted approach in helping participating individuals find safety, stability, and support.

Not everyone experiencing homelessness can adapt to shelter living and these sites provide a variety of options for them to make the best decision for themselves. It is rare we see a city provide a range of options for the homeless. Even if individuals choose not to access the resources and amenities at a location, at a minimum, they have a safe place to sleep, food and water.

There also are plans to bring additional shelters online, with an authorized encampment planned for South 82nd and Pacific Avenue and the conversion of the shuttered Comfort Inn at 8620 South Hosmer Street. Though, it is currently unclear when those beds will become available. As of September 5th, there are 35 available beds across the encampments. Even once those new shelters come online, there will still be a gap between available resources and those 700 or so people who need them.

As the official introduction of the ordinance was delayed, it will likely be reworked before being brought before the City Council. As of writing this article, there is no scheduled discussion or study session regarding the issue.

Tacoma residents can submit public comments about this ordinance to cityclerk@cityoftacoma.org or attend the next council meeting.

Kevin Le

Kevin Le is a Geographic Information Science (GIS) professional in Tacoma. He enjoys studying spatial data to better understand our urban landscapes and redesign cities to better serve all people.