Seattle’s Third Avenue is arguably one of the most successful transit corridors in the entire country. The street consolidates most Seattle bus routes into one corridor that ensures ease of transfers and creates a system that’s easy for visitors to the city to understand. Prior to the pandemic, Third Avenue saw the highest number of buses of any single bus corridor in the entire country and was also near the top for ridership at around 52,000 bus passengers per weekday.

But Third Avenue has been plagued by problems as well. The sidewalks are relatively narrow for a transit mall, leaving very little room for improvements to the public realm that aren’t directly related to transit access. The street has also been long associated with crime. The City of Seattle’s cyclical approach to crime in Downtown, long relying on a regular crackdown on “hotspots,” has failed to put a stop to persistent problems along the corridor for decades, and these actions have impacted on transit users’ experience on Third Avenue. For example, one of Mayor Bruce Harrell’s first acts in office was to close a highly used bus stop along the corridor to “increase visibility into criminal activity,” according to the mayor’s office.

Improving the street has long been a goal of the Downtown Seattle Association (DSA), which commissioned a report in 2019 that came back with several recommendations for how the corridor could potentially be revamped. That effort is now being resurrected, with the Seattle City Council’s public assets and homelessness committee considering a resolution this week that would kick start the conversation again.

“It really hasn’t recovered as a street since the cut-and-cover, original transit tunnel was dug through and under Third Avenue in the early ’90s,” Jon Scholes, president of the Downtown Seattle Association, told the committee.

When the Downtown Seattle transit tunnel was completed in 1991, a pedestrian mall had been envisioned on Third above the tunnel but instead vehicle traffic remained, both buses and general purpose traffic. By the late 1990s, discussions began around creating a transit-only street to make way for frequent rail transit in the tunnel, but it was nearly another two decades until bus traffic finally exited the transit tunnel and was routed onto surface streets, including Third, putting the number of daily bus trips on the street at its highest level.

It wasn’t until 2018 when all-day restrictions on motor vehicles were implemented. In the coming decades, as Link light rail replaces bus trips to different areas of the region, there will be routes that no longer run on Third, but questions remain around how to remake the street so that the quality of transit service is not impacted for the riders who remain.

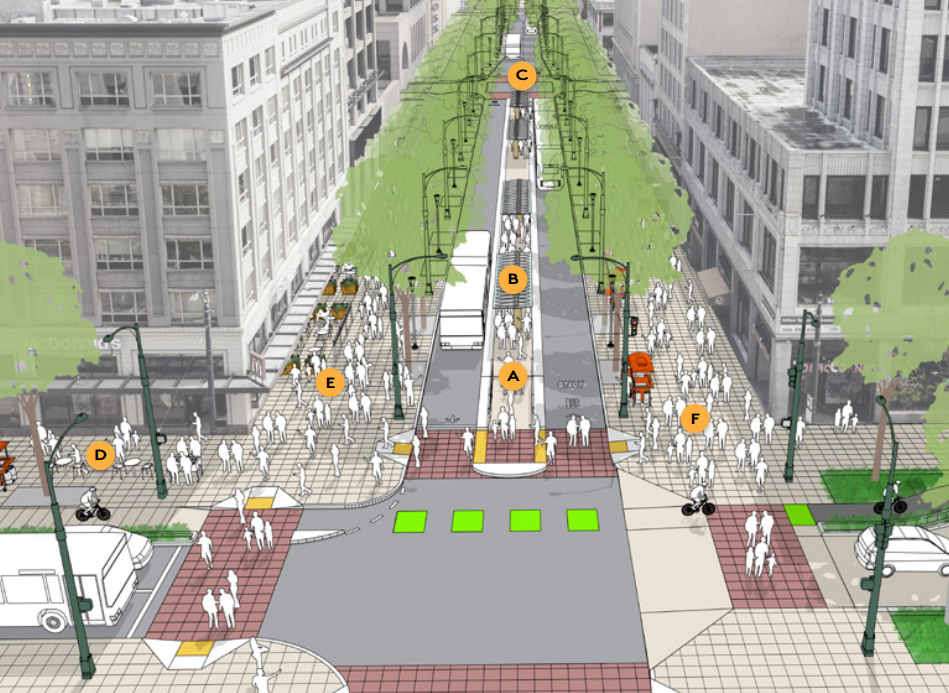

The current version of the resolution being considered by Council doesn’t take a position on what a new configuration of Third Avenue would look like. The concepts developed by the DSA include a number of ways to expand the sidewalks and create space for transit riders to wait for the bus, including one alternative that would create a center median on the street, much like the city is currently doing on Madison Street in First Hill for the RapidRide G Line. The Urbanist went though the entire roster of recommendations that were put on the table back in 2019.

Many of the concepts involve forcing riders to transfer to a different bus at either end of the corridor in order to continue to another part of the city, replacing individual routes along Third with a shuttle. That will likely be a non-starter with a lot of transit riders, who are already contending with reduced frequency on many Metro routes.

Taking away street space for wider sidewalks is one thing, but creating activated spaces along Third Avenue could prove to be a much harder thing to cultivate. The DSA’s vision for the corridor includes renderings showing outdoor seating at Third and Pine, outside the long-established McDonald’s at that corner.

However, an adjacent plan to improve the Pike and Pine Street corridors, set to start construction within a year, had originally envisioned public activation at this corner as well, only to walk back those plans in later stages. Early plans for what was called the Pike Pine Renaissance showed expanded pedestrian space and even a mobile coffee cart outside the McDonalds. Instead, the bike lane will be built closer to the curb and space for parking and loading, steps from a Westlake Station entrance, will be prioritized instead.

The reason cited for this change was an intentional decision not to encourage people to linger in this area but to pass through instead. This illustrates the chicken-or-the-egg conundrum when it comes to activating public space here: Third Avenue likely won’t improve without some new uses, but it’s unlikely those uses will get to be tested for fear they be used the “wrong” way.

At Wednesday’s committee meeting, there was a consensus among city councilmembers that improvements on Third could benefit the entire city. “Third Avenue in many ways really is the front door of our downtown neighborhood,” Councilmember Andrew Lewis said in remarks kicking off the discussion. “It is the place that we all go to, all roads lead there if you are going downtown…if you’re a tourist coming into the city on light rail, the first impression of the city that you’re going to see is going to be when you come up out of the light rail tunnel onto Third Avenue.”

“It’s beautiful. It looks like the kind of thing I would love to be doing on all of our city’s streets,” Morales said of the vision presented in the DSA’s proposal. Just a day earlier, Morales had told incoming SDOT Director Greg Spotts that the city should be “starting where the need is greatest” in terms of transportation improvements. Morales was interested in learning how a conversation around Third Avenue relates to the citywide conversation that is happening as part of the Seattle Transportation Plan and the Comprehensive Plan update. In his answer, Scholes suggested that the project could be eligible (and compete with other city projects) for upcoming federal grant opportunities.

Councilmember Lisa Herbold was interested in getting everyone on the same page on what preserving transit capacity on the corridor looks like. As the process moves forward, and the conversation turns to possibly moving some bus routes off the street, any change to how buses operate downtown could have ripple effects across the entire Metro system. Meanwhile, Councilmember Debora Juarez was interested in how physical changes on the street could impact the issue of crime and expressed interest in how the street could become a template for changes on other streets.

“I think what we’re really seeing, not just in Seattle but nationally and around the world, post-Covid, is this new surge of urbanism to take back spaces for people, activations, an emphasis on placemaking that really centers how we can use a space that was previously dominated by cars or dominated by concrete,” Lewis said. “This is a policy in keeping with that broader movement…and I do hope it serves as a template for how we can continue to reclaim places for bikes, pedestrians, street cafes…and I want to expand that as much as possible.”

The City has mostly excluded Downtown and its dense urban centers from its efforts to reassess how street space was used during the pandemic, only adding a small Stay Healthy Street in Belltown as it was opening up neighborhood streets elsewhere in the city.

Third Avenue, of course, doesn’t have private cars on it that aren’t delivery vehicles, in contrast with most other streets Downtown that continue to be dominated by space for cars. Fourth Avenue’s bus lane, for example, becomes street parking outside of a few select hours per day. While there are certainly opportunities to unlock on Third, it is notable that the city doesn’t seem to be looking a little more broadly at how street space is used in one of the most valuable neighborhoods on the West Coast.

The interagency taskforce envisioned in the resolution calls to mind one created half a decade ago with One Center City, which was developed to prepare for the closure of the Alaskan Way Viaduct, but then given a broader mandate to look at public realm improvements. After some near term improvements were selected, an effort to look longer term was tried as the effort was rebranded as Imagine Downtown, but the effort mostly fizzled out without any sense of urgency behind it. A reimagining of Third Avenue has as much regional significance as One Center City’s efforts, and as much potential, but it also could fizzle out if a broad consensus isn’t reached or other city funding needs take precedent. For now, however, Seattle is signaling that it’s interested in keeping the conversation going.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.