Tacomans contend with their streets and roads

This is the last of three vignettes depicting possible conversations between imaginary people in Tacoma as the city grapples with growth, densification, and other forms of change.

A common topic across all of these stories will be Home in Tacoma, an ambitious plan to overhaul Tacoma’s zoning laws to allow denser and more affordable housing to be built in our neighborhoods. In previous coverage, while we have lauded the plan, we have pointed out deficiencies in equity for both residents and workers. Recently, the City of Tacoma completed the full “Scope of Work” for Home in Tacoma and will soon begin implementing the plan into city policies.

To support and enhance the narratives, we’ve included maps derived from real data. Through these characters, readers are invited to listen in as people in their community deliberate and make determinations within a shifting urban landscape.

From Streetsblog USA:

Cities are, rightly, trying to make themselves more livable for those that do not want to rely on cars — but at this point, we as a society are only beginning to realize that we can’t do it by just throwing paint on the streets… We’re luring bicyclists to their deaths.

Kea Wilson, Streetsblog USA

Molly pulls up to a confrontation between Linda and Marco. She’s driving a red two-door compact. Her neighbors are shouting from inside their cars. Linda parked in front of Marco’s house while he takes up the middle of the street parallel to her. She’d been warned that this would happen all her life, and here it is now: a shouting match between neighbors.

“But this isn’t your spot,” yells Linda. It’s on the street — a public street — I can park there — anyone can park there — if it’s open.

“It’s in front of my house. I always park here,” responds Marco. “You should know.”

“So you’re telling me that this whole strip of street belongs to you? How does that make any sense? And what’s worse, it’s not as if you have one car — you have three, two of which don’t run! You’re taking more space than any of us! You’re taking more space than any of us!”

“There’s no law against parking cars on the street. It’s a free country.”

“You’re right. That’s why I parked here.”

“Park on your side of the street next time!” Marco snaps at them before pulling away, driving on to the planting strip, and backing into a spot on the grass parallel to his other two cars, nearly hitting the utility pole on the parking strip, nearly clipping his own cars in the process. He quickly disappears into his house with the slam of a door.

Molly pulls ahead and slows when she gets to Linda, who is stepping out of her car.

“You weren’t kidding when you warned me about Marco and how terrotorial he gets about the parking in front of his house,” says Molly by way of greeting.

“That was something else, though,” says Linda. “He’s gotten worse about it since your building went up.”

Just then, Marco yells from the steps to his house: “What? Are you going to tell me I can’t park on the grass in front of my house either? Go home!” He steps into his house. Another slam of the door. Another slam of the door.

“Was that just about parking?” Asks Molly.

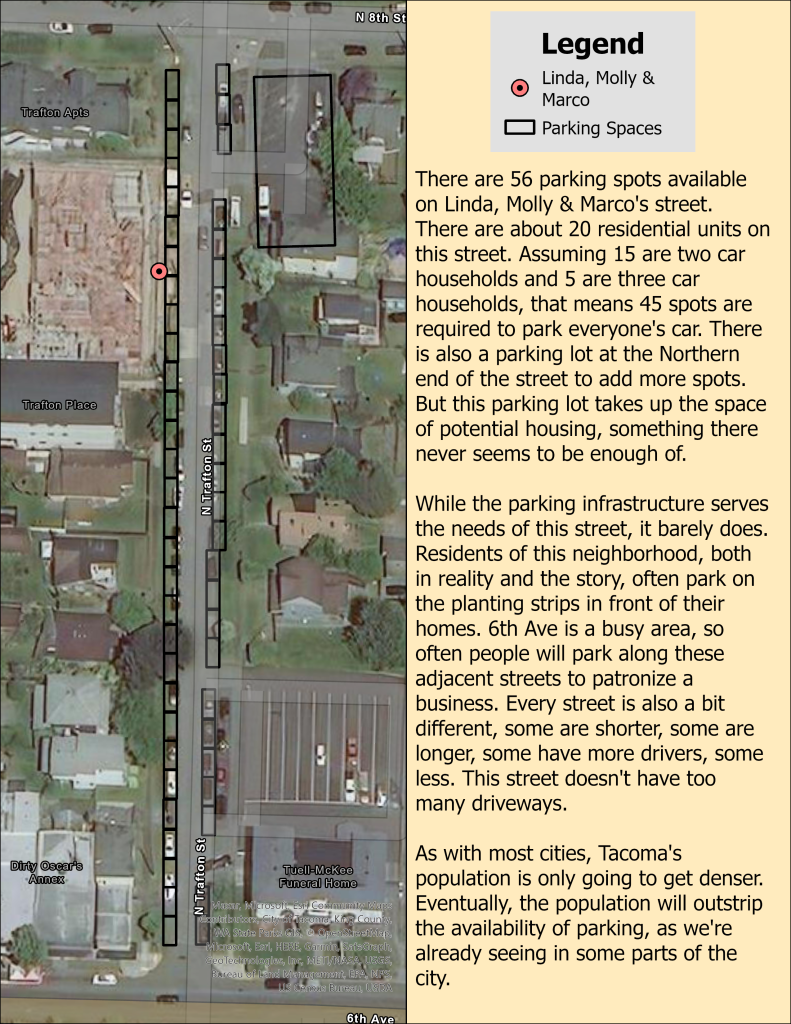

“What else? He thinks he owns the three spots immediately in front of his house. You’re new. Everyone up and down here has exchanged words with him about ‘his parking spot.’ And yet, people are worried about people moving into these new apartments without parking spaces for residents.

After a pause, Linda realizes Molly is in a car herself. “Oh,” she says. “I guess you’re looking to have some words with Marco yourself. New car?”

“Well, new to me, but yeah. I had to.”

“So the bus didn’t work out?”

“Not really. It worked for me sometimes, but not all the time. It worked for me sometimes, but not all the time. Also, my mom was worried about me once the days get shorter. And colder and wetter.” She patted her car door. “This is just more reliable.” She patted her car door. “This is just more reliable.”

“Come over for a few minutes after you park and tell me all about it,” says Linda.

A few minutes later, Molly walks up to Linda, who is snipping dried flowers from her planting strip garden.

Linda looks up and says, “That’s too bad. I really thought you might figure it out.”

“Me too. But it’s not just working. There’s all the other errands to run and weekend trips and all that. I actually even tried riding a bike. I thought I might get an electric bike, but in the end it wasn’t a good idea.”

“Oh? Why’s that?”

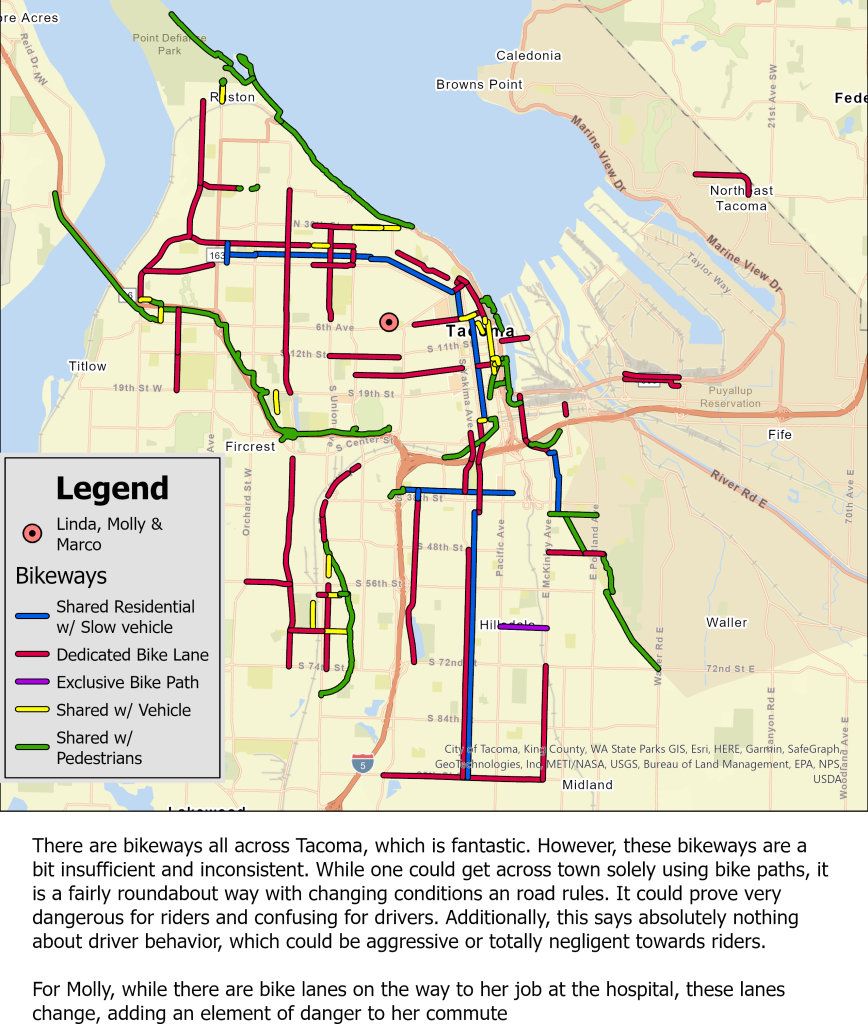

“Well, for one, riding up 6th is a little risky. There’s one stretch of road with a bike lane starting at MLK. It ends three or four blocks from where 6th meets Division and Sprague, and that’s a really tricky intersection to navigate if you’re on a bike or on foot, especially at night.

“Did you try Division?” Asks Linda.

“I did, but there isn’t a bike lane on that road at all. And drivers speed up on that stretch. I didn’t feel safe.”

“Honestly, I’m not even sure bike lanes are that helpful to cyclists in and around the hospitals,” says Linda. “I see cars parked in the bike lane at the intersection of 6th and MLK all the time.”

“Yeah, I know lots of people who would bike more if they didn’t feel that the roads pitted them against cars. Including myself.”

“Tell me about it,” says Moly. “I took a friend’s bike downtown last weekend and between the narrow roads and one-way streets — all of them trying to accommodate moving cars, parked cars, pedestrians, and buses—there’s too much competition on these roads. I never stand a chance against a huge pickup who doesn’t see me coming or whose tail-end is sticking out beyond the parking space. And that’s if you’re not dodging potholes. It’s like an obstacle course between the poor condition of the roads and the oversized cars trying to fit into compact car spaces. Not even talking about how poorly maintained a lot of roads are throughout the city, dodging potholes and rough patches left and right.” A sigh. “And that’s if you’re not dodging potholes. It’s like an obstacle course between the poor condition of the roads and the oversized cars trying to fit into compact car spaces. not even talking about how poorly maintained a lot of roads are throughout the city, dodging potholes and rough patches left and right.”

“An obstacle course. I hadn’t thought about it that way,” says Linda. “And here we are in this neighborhood upset that new developments aren’t accommodating more cars. Well, not me, but so many people in this neighborhood. Did I tell you I went to one of the meetings about making the area around University of Puget Sound a historic district?”

Molly shakes her head. Molly shakes her head. ““I went because someone told me that people seek these designations as a way to prevent upzoning in their neighborhoods. And I do think that’s what this is about, given how people at the meeting at the meeting mostly focused on how apartment buildings would bring all sorts of negative things to the neighborhood, including more cars.”

“What about the historic nature of people’s homes and all that? Lot of these are pretty old. Lot of these are pretty old.”

“I didn’t hear too much about that. Really, it was a lot of hand-wringing about having more people around, more cars parked on the street, and stuff like that. Which is really weird, because so many of the people at these meetings store their RVs and campers on the street for months and months on end, even though they aren’t supposed to.”

“It rings of entitlement to me. They don’t want people to park their cars there, but they do want those spaces available to them for their mostly stationary recreational vehicles. Or, in Marco’s case, for his vintage car collection that barely runs.”

“But you’re the problem, Molly, you and your little two-door used car.” Linda winks and smiles at Molly when she says this.

“Yeah, I guess I am.”