A new policy included in Move Ahead Washington could vastly improve bike and pedestrian access and safety on state highways.

When the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) repaved the entirety of Seattle’s Lake City Way, also known as State Route 522, between I-5 and city’s northern limit between 2020 and 2021, the department added ADA-compliant curb ramps that were missing along the corridor. And in partnership with the Seattle Department of Transportation, they added spot improvements to some of the pedestrian crossings, including adding a new signal at N 135th Street. But the street’s layout, which includes two wide lanes in each direction and a center turn lane, with a curb lane that is used for both parking and as a bus lane for a portion of the corridor, remains unchanged after an approximately $15 million repaving.

The entirety of Lake City Way in Seattle makes up four miles of a staggering 1,142 miles of state highways that provide no space for people biking, according to WSDOT’s 2021 Active Transportation Plan. Just ten miles of state highways that run through population centers have any space for people to bike on. While there is still no safe place to bike along the Lake City Way corridor, things might have gone differently if WSDOT was starting work on the repaving project now, thanks to a provision that the state legislature included in the Move Ahead Washington transportation package, passed this spring.

“In order to improve the safety, mobility, and accessibility of state highways, it is the intent of the legislature that the department must incorporate the principles of complete streets with facilities that provide street access with all users in mind, including pedestrians, bicyclists, and public transportation users, notwithstanding the provisions of RCW 47.24.020 concerning responsibility beyond the curb of state rights-of-way,” the bill, SB 5974, states.

The legislation goes on to detail how with every state transportation project that started design after July 1 of this year with a cost of over $500,000, WSDOT should identify gaps that exist in pedestrian or bike networks, and work with local jurisdictions to fill them. That section of the law also explicitly directs WSDOT to reduce the speed limit on its state highways “to achieve the desired operating speed in those locations where this speed management approach aligns with local plans or ordinances, particularly in those contexts that present a higher possibility of serious injury or fatal crashes occurring…in keeping with a safe system approach and with the intention of ultimately eliminating serious and fatal crashes.”

“The Complete Streets direction in SB 5974 is transformative in its approach because it is a mandate that applies to nearly all highway transportation projects,” WSDOT spokesperson Emily Glad told The Urbanist. “One of the effects of SB 5974 is that active transportation, such as walking or biking, is now defined by state law as a baseline need that must be considered any time a project affects a state roadway. This means that all projects must now analyze and incorporate improvements regardless of the long-term budget assumptions in that program.”

This summer, the department released a memo to all WSDOT Project Development Engineers statewide providing specific direction on following the new state law. Given the direction from the legislature, “it is the stated policy of the Department to incorporate the principles of Complete Streets with facilities that provide street access with all users in mind, including pedestrians, bicyclists, and public transportation users, on projects to be constructed on state highways,” the memo states.

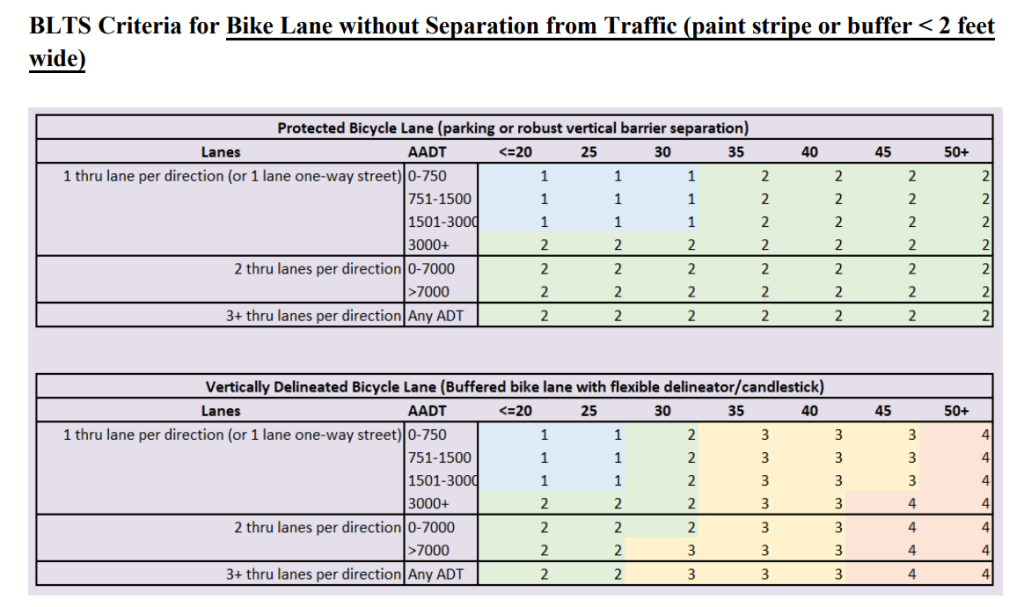

The memo then goes on to detail what the state highway department’s standards for complete streets facilities on state highways are, using a Level of Traffic Stress (LTS) threshold. It gauges how appropriate a facility type would be based on how comfortable someone would be using it: the lower the LTS level, the better. WSDOT’s “design goal” is for a facility to have a LTS of 1 or 2. In terms of bike facilities, WSDOT only deems a mixed-use facility, e.g. no separated bike lane, if a highway has only one lane in each direction, and a speed limit of less than 20 miles per hour, or a speed limit of 25 miles per hour if the street sees fewer than 3,000 vehicles per day.

On the vast majority of state highways, a parking or barrier protected bike lane will be what will meet WSDOT’s standards: per the memo, every roadway configuration would provide either a LTS 1 or 2 with that type of bike lane. A flex-post bike lane would meet the criteria only in certain circumstances, like on two lane highways with lower traffic volumes or with lower speed limits. Lake City Way, which has high traffic volumes and a 35 mile per hour speed limit for most of its length would need to be designed to accommodate a fully protected bike lane under these standards.

But there are going to be exceptions, and those exceptions will determine what the true extent of this policy change will be. WSDOT’s proposed design changes will be developed in conjunction with local jurisdictions, where tradeoffs like the removal of parking or a perceived diminishing of vehicle capacity will become quickly apparent as the agency goes through public engagement. But no longer will a lack of funding from a local city or county become a reason that a bike or pedestrian network gap can’t be filled.

“SB 5974 has established that Complete Streets must be built so that multiple sets of legislative expectations are met when working in a location,” Glad said. “It means WSDOT can improve walking and biking facilities while we’re working in a community — one work zone, multiple benefits in safety and space-efficient transportation as well as preservation of the existing infrastructure. It also means that WSDOT will revisit previous cost estimates on projects that have not yet been designed.”

WSDOT Secretary Roger Millar emphasized that element of the policy change earlier this year in remarks to the Washington Transportation Commission.

“Our preservation program will include investments that close those [bike and pedestrian network] gaps…but that will result in money being spent on those facilities as opposed to stretching the money out to do more pavement and more bridge work,” Millar said. “I think that’s consistent with taking a multimodal approach. Again, a quarter of [Washington residents] don’t drive. We need facilities in a state of good repair as well.”

In other words, the legislature is giving marching orders that the maintenance dollars it has allocated should be also going to make existing projects more whole.

Asked for a specific instance of where the policy is having an effect, Glad pointed to the aging Omak Bridge across the Okanogan River in north-central Washington. Previously the bridge was planned to be refurbished and widened by removing sidewalks, with a separate pedestrian and bike bridge built just to the north. Now, in part due to this guidance, WSDOT is recommending a full replacement of the bridge with a bike and pedestrian facility included, in line with Complete Streets direction. The bridge currently provides the only connection between downtown Omak and the city’s largest park, which makes a safe biking route important. Whether the new multimodal bridge would provide a better biking and walking connection that the alternative of adding a new pedestrian bridge nearby will depend on the design. It’s an early test of how much the new policy will truly improve access.

The Urbanist will be on the look out for additional examples of the new policy at work and the tradeoffs come into play.

So far, this new policy change looks to be one of the more game changing elements of the Move Ahead Washington era. For years, bike and pedestrian advocates have had to push with every new state highway project, from expansion project to repaving, to ensure that every opportunity to add facilities was utilized. Now, the legislature seems to have taken a huge step forward in ensuring that happens automatically.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.