Alex Pedersen became the first Seattle City Councilmember to outline his own proposal for the once-a-decade Comprehensive Plan update toward the bottom of his official newsletter distributed this past Friday. While couched in progressive-sounding anti-displacement language, Pedersen’s proposal, which he calls “Alternative L,” in effect would be a very conservative one. Pedersen proposes to allow sixplexes, but only for all-affordable projects directly on frequent transit lines.

The Urbanist reached out to nonprofit housing developers but couldn’t find any who had been consulted on the brand new proposal, and some in the affordable housing industry said the proposal didn’t appear to be workable and would produce very little additional new housing — low income or otherwise — as outlined. Perhaps that was the point.

Pedersen sharply opposed Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) rezones in 2017 and hired one of the homeowner activists (Toby Thaler) who sued the city to block the rezones (repeatedly) as his legislative aide once he was elected as District 4’s councilmember in 2019.

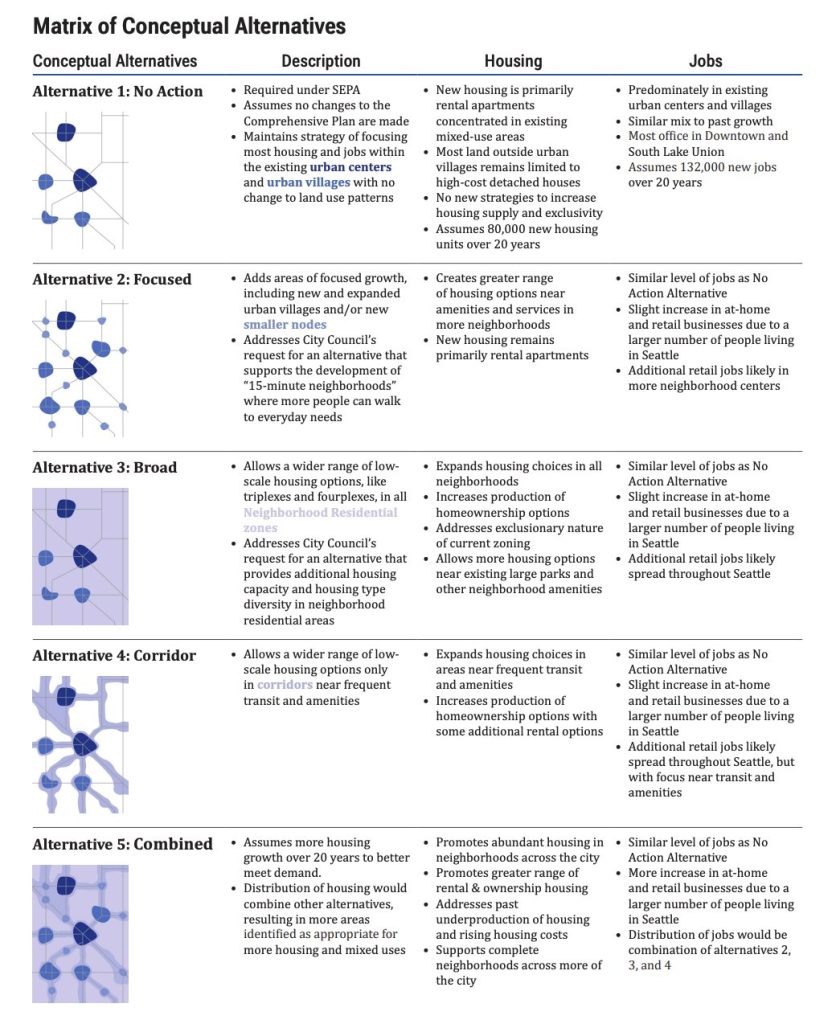

In June, the Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) released four concepts, in addition to a no-change baseline alternative, in preparation for the Major Update to the Seattle Comprehensive Plan due in 2024. The Housing Development Consortium (HDC), which represents nonprofit developers and their partners, came out in favor of an expanded version of Combined Alternative 5 and adding an even bolder Alternative 6 for the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The Urbanist also backed that position. Pedersen’s proposal was released just days after OPCD closed its comment period on those alternatives.

“After careful consideration, I have concluded that the five initial alternatives presented by OPCD are inadequate in the face of our city’s affordable housing and homelessness crises, because no alternative prevents the demolition of existing affordable housing and no alternative requires any production of low-income housing in exchange for giving away increased density benefits to the for-profit real estate development market,” Pedersen wrote. “I, therefore, propose adding to the ‘One Seattle Plan’ EIS an alternative that directly meets the goals of preventing displacement and producing low-income housing.”

While Councilmember Pedersen’s office declined to answer The Urbanist‘s questions, what he revealed in his newsletter suggests his proposal is centered around maintaining the status quo, avoiding effective upzones, and discouraging additional housing outside of existing Urban Villages and Centers, which account for just 10 square miles of Seattle’s 84-square mile total. Meanwhile, Seattle dedicates 30 square miles to low-density “Neighborhood Residential” zoning, which is dominated by single-family homes that increasingly sell for more than one million dollars.

Maintaining restrictive zoning across 75% of residential zones while jamming nearly all housing growth (more than 80%) into 10 square miles has created two Seattles over the past three decades since the Urban Village growth strategy went into effect. While Mayor Bruce Harrell has branded the Comp Plan update “One Seattle,” such lofty egalitarian ambitions do not appear achievable with Pedersen’s approach. Two Seattles would remain: wealthy single-family enclaves and the narrow bands along busy highways and arterials where apartments would be confined to.

Still, Pedersen appears content to brand his alternative as the opposite of what it would actually achieve. The L stands for low-income housing, Pedersen writes, but the 50% of area median income (AMI) requirement for rentals makes the zoning nearly impossible to pencil out for affordable housing developers. The subsidy required is large, and federal subsidies, such as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, are geared toward larger rental projects, which provides little route to get smaller projects off the ground.

The ownership option at 80% of AMI looks slightly more attractive, but it would still require significant subsidy, and it’s not clear there’s a scalable model there or an organization prepared to grab that baton. A representative with the King County chapter of Habitat For Humanity said their organization hadn’t been consulted about Alternative L, and noted affordable ownership funding is limited in Washington State, which would make it difficult to scale up sixplexes across the city — unless Pedersen was also lining up a major new funding source.

“Alternative L: “the Low-Income Housing Alternative”:(1) On existing frequent transit arterial corridors in Neighborhood Residential zones, permit multifamily developments of up to 6-unit stacked flats (per each 5,000 square foot lot) requiring 100% low-income housing [defined as rental units affordable to households below 50% of area median income (AMI) or homeownership units affordable at 80% of AMI] and (2) to prevent displacement, projects demolishing existing, affordable single family rentals or affordable multifamily housing in any zone would need to adhere to existing zoning (i.e. not allowed to profit from density increased after 2022). The “L” stands for low-income housing, because that’s what we need.

Councilmember Alex Pedersen from August 26, 2022 newsletter

Pedersen acknowledged the Alternative L is similar to OPCD’s Alternative 4, but pointed out that his would stifle market-rate development, which he sees as a virtue.

“One may try to argue this new Alternative L could fit into OPCD’s Alternative 4 (see below for OPCD’s initial alternatives),” Pedersen wrote. “I disagree that my proposed Alternative L would fit into Alternative 4, because OPCD’s Alternative 4 does not require any low-income housing, it does not prevent demolitions of affordable housing, and — in a move that could encourage an increase in the use of polluting single occupancy vehicles — it gives free reign to developers ‘near’ frequent transit rather than strategically on transit corridors.”

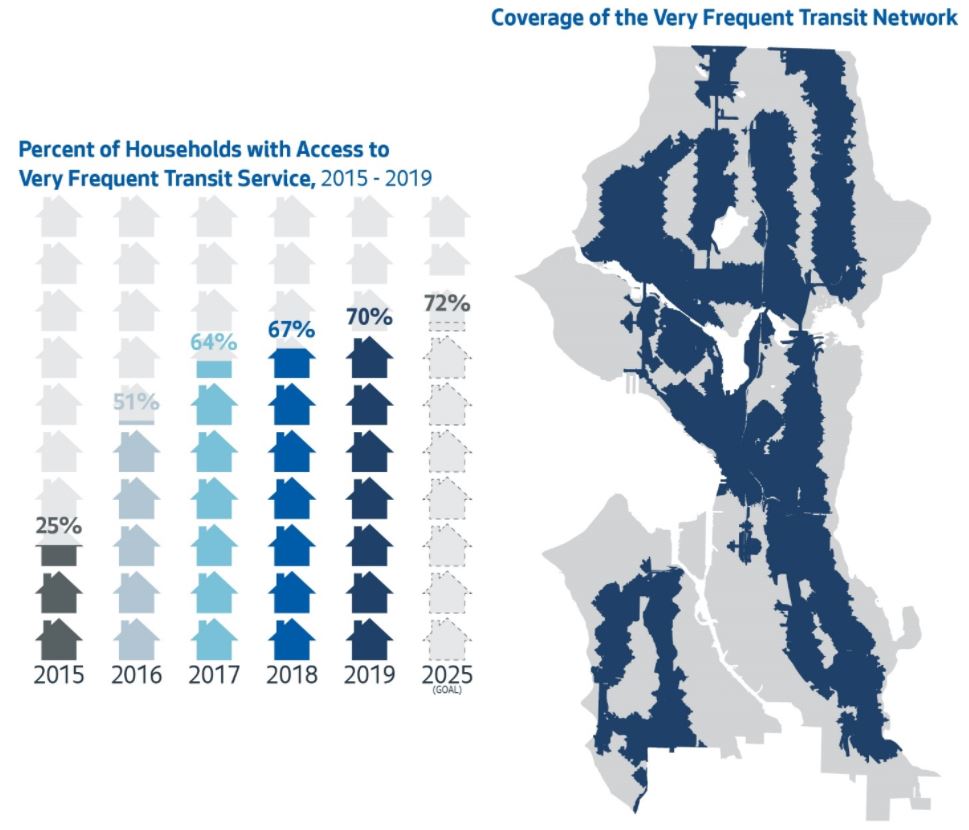

Oddly, he argued adding dense in-fill housing within an easy walk of frequent transit in Seattle would lead to an “increase in the use of polluting single occupancy vehicles,” which betrays that he does not take a regional view to climate pollution. If Seattle blocks growth, that means more growth in sprawling suburbs, where car use will be far more prevalent, and people are still likely to drive their polluting vehicles into Seattle, for that matter. People do not simply evaporate when Seattle pulls up the metaphorical drawbridge. Most often they move to places where their carbon footprints and environmental impacts are higher.

The other issue is that Pedersen implies tenants are clamoring to live directly on “transit arterials,” which include highways like Aurora Avenue or Rainier Avenue — often the deadliest, more crash-prone roads in the city.

“The private market would surely attempt to maximize profits from changes in City policy by demolishing existing affordable housing and then developing small units and/or townhomes that are less accessible to people with impaired mobility, including seniors who want to age in place and families needing larger units along transit corridors,” Pedersen wrote.

In fact, tenants and housing advocates have been calling for more apartments that are on quiet, shady, calm streets with clean air where their kids can play and families can bike without fearing for their lives. This can’t be achieved if only the blocks immediately on the transit corridor are upzoned. Plus, given the locations of Urban Villages, many of these blocks are already zoned for apartments, anyway. As transportation committee chair, Pedersen has supported proposals to run less bus service in the city, including when he voted against an increase in Seattle’s supplemental sales tax to fund Metro service. If he had his way, even less of the city would be available for affordable housing.

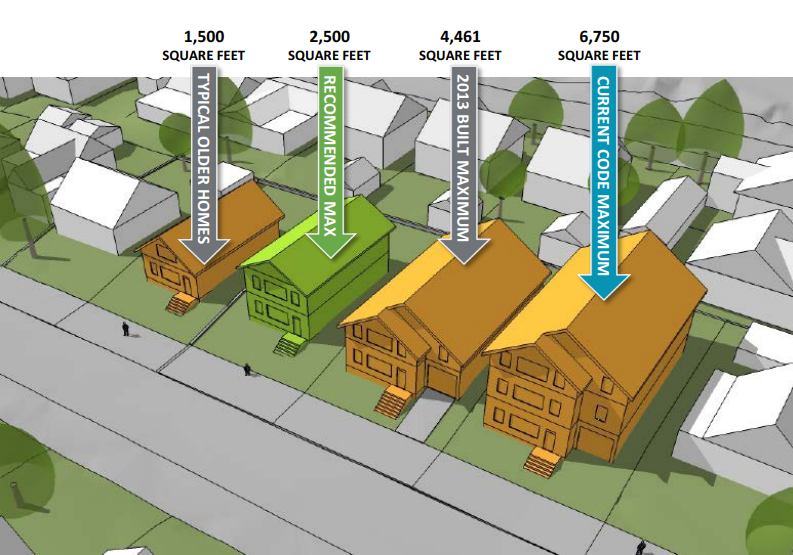

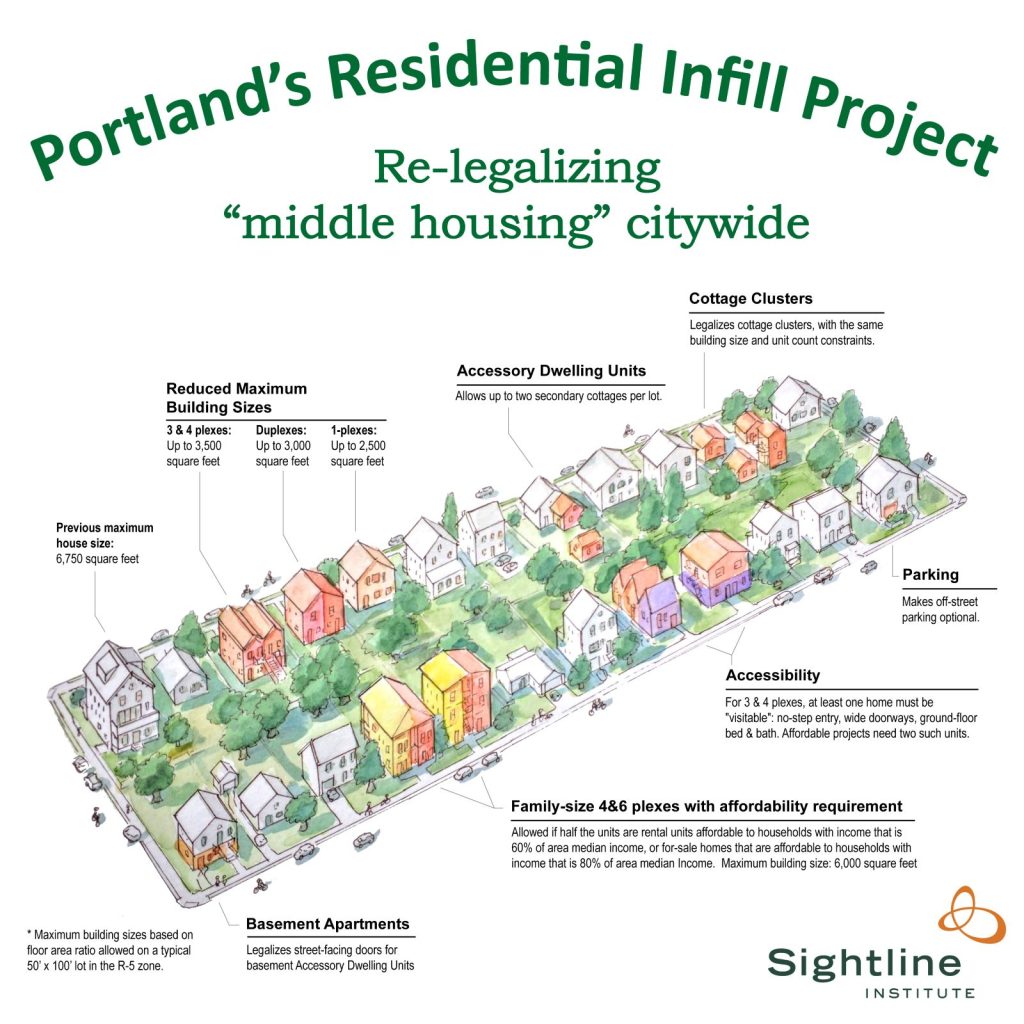

Questions from The Urbanist sought to clarify if Pedersen’s proposal would prevent single-family home teardowns for construction of million-dollar mansions — a prevalent trend in Seattle. Portland dealt with this problem by capping the size of new homes as the city implemented its in-fill project allowing fourplexes citywide and sixplexes if half the homes are affordable. Alas, we did not hear back from Pedersen over the last five days.

Pedersen’s argument gives the impression that Neighborhood Residential zones are prevalent sources of subsidized low-income housing and naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) that is privately owned. He also claims massive amounts of NOAH units are being demolished across the city. There is no evidence that’s true — The Urbanist requested it.

“After the upzones of the University District by a previous City Council, we have seen demolitions of naturally occurring affordable housing at a higher rate than promised and we have seen nearly all developers opting out of building affordable housing in that neighborhood where many struggle to pay rent,” Pedersen wrote. ‘A similar pattern appears to be unfolding in many of the communities upzoned recently in conjunction with ‘Mandatory Housing Affordability’ (MHA) policies. Instead of providing affordable housing onsite, these developers have written a check to pay an ‘in-lieu’ fee that the City uses to fund different projects approximately three years later somewhere else, which is not ideal.”

This statement invokes bad math from the Seattle Displacement Coalition from the MHA fights in 2017 that misleadingly claimed market-rate apartments in the U District were still affordable and would remain so if the City didn’t do the upzone in the neighborhood. Luckily, the city did do that rezone and now the U District is leading the city in MHA contributions.

Moreover, Pedersen conveniently overlooks OPCD’s calculation that in-lieu fees actually produce more affordable housing than on-site performance does. He also sidesteps the issue that expanding zoning for apartments or other denser housing and then actually encouraging that development would result in far more MHA contributions. Single-family construction and renovation do not contribute MHA payments. Only upzoning in the narrowest circumstances like he proposes would lead to more free-riding single-family development that doesn’t contribute to the city’s affordable housing trust fund.

By the way, The Urbanist also asked if he supports rent control as an anti-displacement tool. Still waiting.

Finally, Pedersen closes with a frequent canard by anti-tenant homeowner activists: that enough zoned capacity exists so why bother adding more? “One can argue that today’s allowable development capacity from the existing ‘2035 Comp Plan’ adopted in 2016 can already accommodate the growth envisioned by the forthcoming 20-year Comp Plan dubbed the ‘One Seattle Plan’: a total of 112,000 new units is only 5,600 additional units per year. During the six-year period from 2016 through 2021 (which includes two years of the pandemic), 47,514 new units were produced, which is an average of nearly 8,000 new units per year,” he wrote.

This appears to misinterpret growth targets set by King County based on guidance from the Puget Sound Regional Council. Just because Seattle has averaged nearly 8,000 new units over the past six years does not mean it will continue to manage that rate of production — at least without providing additional land for such development and ensuring that the design review and permitting process is running smoothly and not crushing projects with unexpected delays and fees. A do-nothing approach would also not comply with the Growth Management Act, which sets minimum targets for affordable housing. It appears unlikely Alternative L would comply either despite Pedersen’s bluster.

What Alternative L appears to be is a red herring intended to derail conversations Seattle needs to have about equitably providing and distributing housing across the city and taking our affordability crisis and climate catastrophe seriously. Hopefully, Pedersen’s colleagues don’t take the bait and stay the course.

Author’s note: This article has been updated to note that King County officially set the growth targets, not the Puget Sound Regional Council, which does the study that sets growth expectations.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.