One saga demonstrates the difficulties developers face in getting infill projects permitted, even after reforms meant to encourage them.

The City of Seattle permitting process for new housing is riddled with impediments that disproportionately challenge the small business owner seeking to acquire permits to build much needed smaller housing projects.

In 2019, the Seattle City Council amended the zoning code to add flexible allowances for the installation of attached or detached accessory dwelling units (ADUs and DADUs). Builders have demonstrated the potential of this code to address middle income housing with infill redevelopment of single-family lots with three-story side-by-side dwelling units.

With the exception of the streamlined system for backyard cottage permits, the permitting process is plagued with unanticipated curveballs, time-consuming procedures, and project-crushing mandates from the various departments including the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI), Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), and Seattle Public Utilities (SPU).

The Seattle permitting process, like that of many jurisdictions, starts with a preliminary meeting prior to a formal permit submittal. In Seattle, this meeting results in the issuance of a PAR (Preliminary Assessment Report). Within the PAR, the objective is stated — to help the applicant create a complete submittal package and reduce the need for corrections once the application is submitted.

The objective is woefully underachieved based upon the numerous PARs I have viewed in my capacity as a civil engineer. Anecdotally, I have also heard from other professional civil engineers who agree that PARs issued by the City of Seattle do not provide project specific information required for an efficient and successful initial design.

Instead, the PARs are filled with procedural and administrative requirements, boilerplate sentences, hyperlinks to checklists, and include little or no substantive design information. Without applicable project specific information disclosed, it is not possible to achieve the goal of helping the permit applicant to create a complete submittal package and reduce the need for corrections.

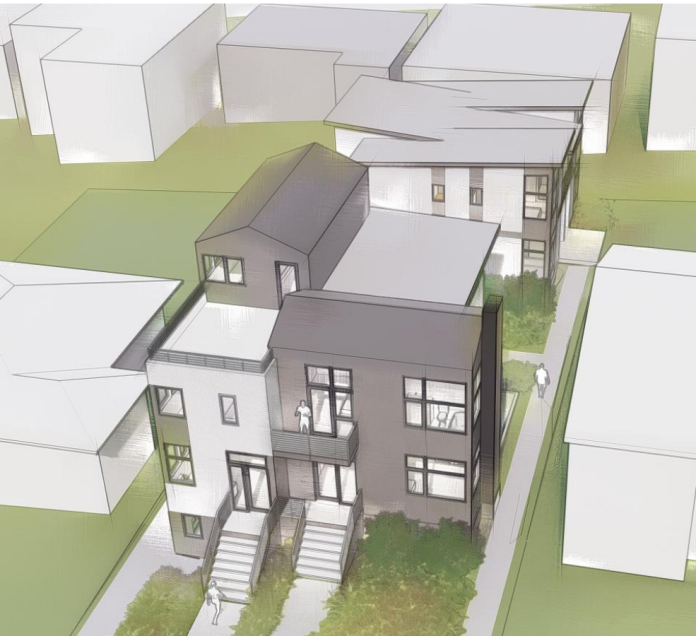

One specific project for which I was the civil engineer of record, was a project to use the ADU/DADU code to construct six new dwelling units. The project was located on 21st Avenue S within the North Rainier Urban Village. The architect provided a design that would result in removal of an older house on a single lot and construction of six new units. The rendering below submitted to the City of Seattle, includes two buildings, each with side-by-side units and the front units each having a basement ADU.

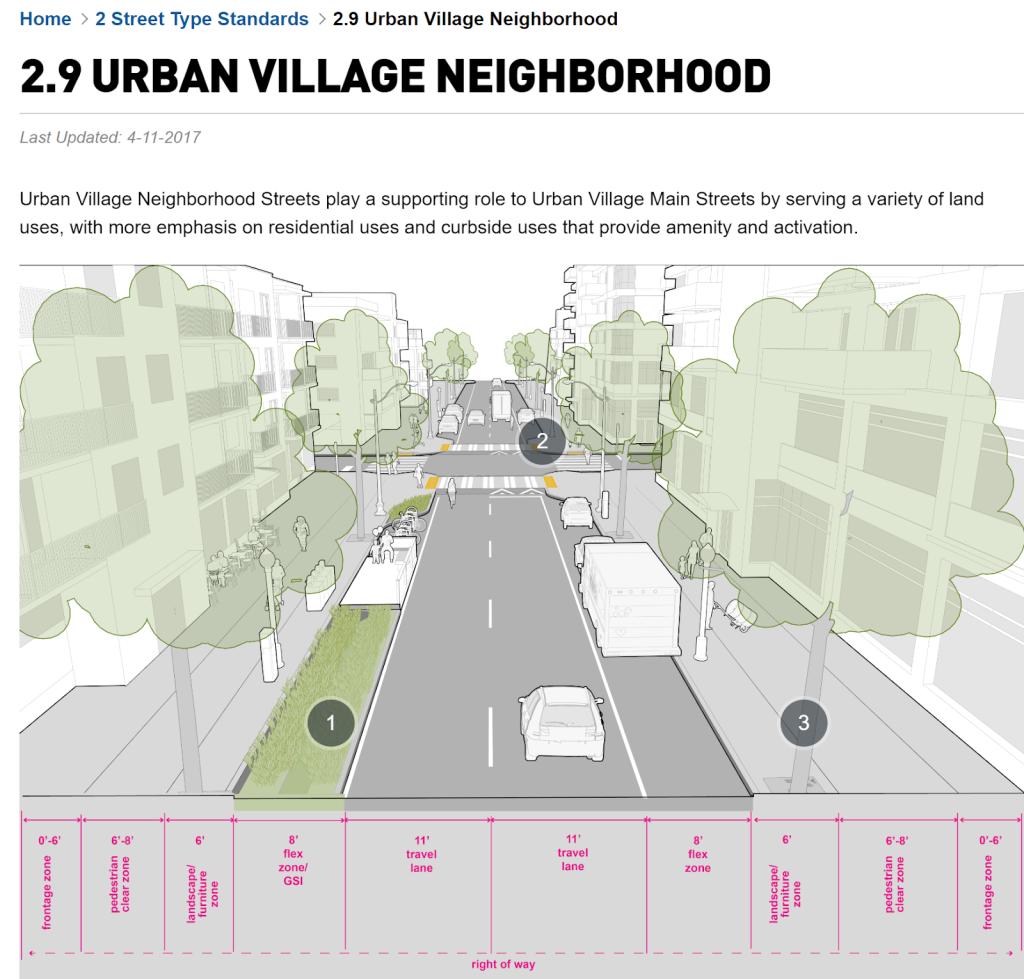

Before the actual building permit application is accepted by SDCI, the applicant must navigate the SDOT permitting labyrinth to determine the street frontage improvement requirements. This starts with a permit application for the Street Improvement Plan (SIP). The civil engineer, which was me, was tasked with providing a design of the curb, gutter, and sidewalk street frontage improvements. However, the PAR did not include the street type nor the required width of the planter strip or sidewalk.

Additionally, SDOT’s Seattle Streets Illustrated Design Manual would lead one to believe that the design standards are already determined for specific types of streets. However, this is not the case. I have completed several designs in Seattle and was curious as to why it was such a rollercoaster to get through a simple street frontage design process. I received my answer during a July 2021 virtual meeting with an SDOT employee who informed me that all applications for frontage improvements of curb, gutter, sidewalk and planter strip are reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

Why the City has published a Complete Streets/Seattle Streets Illustrated Design Manual and wastes the time of civil engineers as well as other design professionals, to somehow think there are pre-approved geometries for different street types, has not been explained to me.

Because the required design information is not provided within the PAR, and the City’s procedure is to react to permit submittals on a case-by-case basis and I, as the civil engineer, am placed in the uncomfortable position of making an educated guess for the width of both the sidewalk and planter strip in order to prepare the initial design plan for the SIP. For this project, my professional engineering conclusion was to use the Urban Village Neighborhood template for a residential street frontage design, and my initial design depicted a six-foot planter strip next to a six-foot sidewalk.

An application for the SIP was submitted in early 2020 with the design geometry I proposed. Then began the uncharted territory of comments from SDOT permit review staff and the subsequent absurdity of the undecidedness from SDOT that was revealed as the case-by-case review process played out. Initial comments required that the planter strip width be changed from six feet to an excessive 13 feet. Then upon submitting the 13-foot design, it was returned with a comment to change the planter strip to 11.5 feet. Then upon submitting the 11.5-foot design, SDOT staff responded with a comment to change it to 10.5 feet. This process used by SDOT took an arduous eight months to complete.

Having extracted the design information from SDOT via the cumbersome and time-consuming process, the frontage design geometry was approved. It seemed the project had overcome the hurdles within the SDOT permitting process and there was a sense of relief that the challenges of the SDOT process were behind us. However, this perceived jubilation was short-lived.

The SDOT review and SDCI review do not occur simultaneously. In fact, the SDOT frontage geometry must be approved before submittal of the architectural building permit plan can be submitted to SDCI. Having attained the SDOT approval, the project proponent was able to submit the architectural building permit plan set.

Thereafter, project-crushing information was released from Seattle Public Utilities (SPU). In December 2020, a full year after the PAR was released, SPU revealed that the water main fronting the property and within 21st Avenue S was not suitable for connection of any new water meters. Without domestic water service, the project was clearly impossible.

According to standard procedures, water review should have happened in early 2020. However, the project was the victim of a glitch as the City transitioned to a new permit software which failed to inform SPU and trigger their review process. The City become aware of this glitch and sought to manually triggered water reviews, but some projects slipped between the cracks. The fact it was not manually marked was explained by a SDCI permit tech in an e-mail from December 16, 2022: “When the City transitioned to the new permit software, the water review had to be manually triggered. The system has since been updated so that the water review is automatic.” Thus, the update was after this project had suffered from the fact it was not manually marked, and a water availability certificate was not issued in a timely manner.

Permit fees were paid in good faith, design services were acquired from the surveyor, architect, structural engineer, and myself the civil engineer. However, all the hours of effort, and the use of monetary resources, were completed in vain, and the small business construction company owner who was the project proponent, had no choice but to abandon the project and cut his losses. (Editor’s note: Instead of being converted to six modestly-sized homes, the single-family home was renovated and sold for $1,130,000 in 2021 according to property records. Since single-family home renovations aren’t required to add sidewalks or planting strips, none were added on a street that lacks them.)

By virtue of the combined actions and procedures of the permitting departments of SDOT, SPU, and SDCI, a state of duress had been created. There is no accountability between departments and it leaves the applicant to try to harmonize a design when the permit systems of Seattle are fragmented and split among different departments with no cohesive master permit system in place.

The project proponents were recoiling from the fact that no new water meters could be connected to the existing water line, when SPU suddenly had a solution to the problem they had created. If the project proponent agreed to pay for the design and construction costs for installation of a new water valve in an undisclosed location, then connection to the water service would be allowed after all. This was a bait, switch, and attempt to hook a small construction business owner into paying for a systemwide upgrade to install a new valve.

This was no normal eight-inch water valve. A unique valve would have to be fabricated for the specific application and a specialized contractor needed for installation, which apparently is due to a non-standard 24-inch water main underneath 21st Avenue S.

Numerous other factors including the fact the SPU had not made a specific determination of exactly where the valve was to be located, and that the project proponent would pay for analysis required and determination thereof. No detailed information or costs would be provided until after the project proponent signed the SPU contract.

The unproportioned burden of systemwide upgrades should not be placed on small projects when there is no direct nexus between the project and the system upgrade. Connection to the water line was determined to be allowed after all. The installation of a valve has nothing to do with a connection for new water meters.

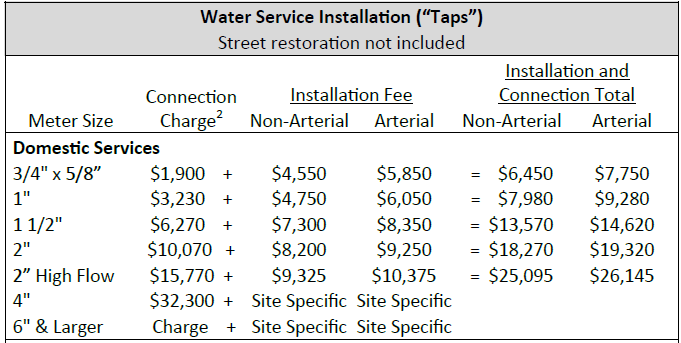

Design and installation of system wide upgrades such as an installation of a valve, are to be borne by the entity who manages the water system, in this case SPU. Mitigation fees are charged for water connection of new meters and this is the system already in place. Each individual project pays for the impact that project has on the system via fees charged for new water meter service installation. These fees charged are to be pooled into a monetary resource to address overall system upgrades.

For one-inch water meters, which are commonly installed for a new housing unit, the fee is $7,980. For large apartment complexes, the fees can be in the hundreds of thousands.

In my professional opinion, the actions of SPU are defined as extraction, and are not supported by the rule-of-law and the concept of direct nexus and proportionality. Since SPU is a separate permitting department, with no checks-and-balances built in for accountability, they were able to withhold information from the PAR, allow permit fees to be paid, allow the applicant to be strung along, creates a state of duress, and then offer a solution that is actually a form of extraction.

The insidious solution offered by SPU was too much burden to be placed on a small six-dwelling unit project — there is no economy of scale to carry the costs. In reality, per the rules used by SPU, the project was infeasible from the day of issuance of the PAR, though the project proponent was unaware, since substantive information was withheld. A full year of efforts by the design team and the small business contractor was for naught.

These combined actions by the permitting departments takes its toll, creates a state of duress and results in knocking-out small business contractors from doing business in Seattle. The small business contractors using private sector funding sources, are essential to the redevelopment of underutilized single-family lots to create much needed additional middle-income housing.

I don’t think the City of Seattle charter says they are incorporated to put small businesses out of business. However, the permitting practices of the City not only crush housing projects, they can crush the small construction business owner who is speculating that successful permit issuance can be achieved in a reasonable time and without burdensome requirements.

The small business contractors are needed to fuel the construction of middle-income infill housing in Seattle. Instead, they are being pushed out of Seattle by unjustified mandates and time-consuming procedures and policies inherent to the City of Seattle permitting processes.

Editor’s note: The Urbanist reached out to Seattle Public Utilities seeking their response, and public information officer Sabrina Register said “We reviewed our records for this project and determined we followed our standard processes for working with and communicating with the project representatives.” She added, “SPU always provides a complete cost estimate before asking a developer to sign a contract.” Provided this response, Breske replied: “It is unfortunate that the SPU standard process is to withhold significant project-crushing information from the Preliminary Assessment Report… Furthermore, in response to the SPU response that developer costs are determined before any contract is executed, below is the information that was provided within a 12-11-2020 e-mail from an SPU staff member:

- Our Water Line of Business has noted the preliminary approximate location within the intersection of 21st Avenue S & S Bayview Street. The exact location would be determined during plan review within the contract process.

- Typically, in these instances, due to the complexities of the site having a 24” inch main, SPU would be completing the design. At this stage I cannot concretely state whether SPU would for sure be doing that in this instance. This would be determined as well during review with your assigned project coordinator.

- We’re unable to find a recent example that would align with your project needs at this time. It’s difficult without have a drawing from our Water Line of Business which typically doesn’t occur until the contracting process.

The SPU response provided to The Urbanist is listed in full below:

“Seattle Public Utilities (SPU) partners with developers to efficiently connect them to Seattle’s water, wastewater and drainage utilities in a manner that preserves the integrity and reliability of the existing systems. SPU understands that Seattle needs more residential development and that utility connections are an important component of making that happen. We reviewed our records for this project and determined we followed our standard processes for working with and communicating with the project representatives.

New segments of water main and conversions of feeder mains to distribution mains through the addition of one or more valves are the two most common system improvements required by SPU. This process is part of a citywide “growth pays for growth” model which is outlined in Seattle Municipal Code and SPU policy.

SPU received a Water Availability Certificate (WAC) application for this address on 11/20/2020. Because the existing main the developer requested to connect to was built in 1915 and no longer meets SPU requirements for tapping, we responded to the WAC application by requiring a valve as a system improvement to convert a feeder main to a distribution main. A new segment of water main would have been the standard requirement, but SPU exercised the flexibility available in policy to offer the valve installation as a cheaper alternative to the developer.

Developer costs are determined before any contract is executed. SPU always provides a complete cost estimate before asking a developer to sign a contract.

SPU appreciates feedback from developers and evaluates ways to continuously improve communications with them.

We remain happy to discuss these issues directly with the developer or their legal representatives. The requirement for a system improvement was outlined in the Preliminary Assessment Report.”

Sabrina Register, PIO for Seattle Public Utilities

Finally we’ll close on Breske’s rebuttal:

“This lack of acknowledgement of the rules-of-law within the permitting department of SPU is a major contributing factor to absurd and project-crushing conditions placed on projects as a condition of permit issuance,” Breske said. “How can a permitting departments not engage and harmonize into its decision-making process the rules of law relative to what is allowed as a permitting condition? It is past due time for permitting departments to also be trained to understand and execute the rules of law applicable to permitting and stop the systems of extractions to require more than that which is legally allowed.”

Donna Breske (Guest Contributor)

Donna Breske is a licensed Professional Engineer in the State of Washington. She owns Donna Breske & Associates and with her staff provides land use consulting and civil engineering design for numerous infill projects within multiple jurisdictions in the Puget Sound Area. She has a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering from the University of Washington and an MBA from Seattle University. She is married to her husband Fred with whom they share two adult children. She grew up in Seattle and is passionate about eliminating absurd impediments from permitting departments and ensuring consistent and predictable outcomes.