Last month, Urbanist reporter Ryan Packer wrote about how the massive SR 99 tunnel project in Seattle is bleeding money due to traffic being far below projections. Tolling was supposed to be a moneymaker to help cover bonds, but instead it’s not even covering operating costs, which suggests a bailout is needed. That $4 billion blunder invites a lot of what ifs.

For me, a big one is: what kind of people-centered mobility improvements could we make if we weren’t suffering from a bad case of car brain? What kind of investments would actually accrue real benefits for our city rather than continue to cost us over time? In an era of droughts, heat waves, and floods caused by climate change, how can we best use public streets to adapt to changing conditions?

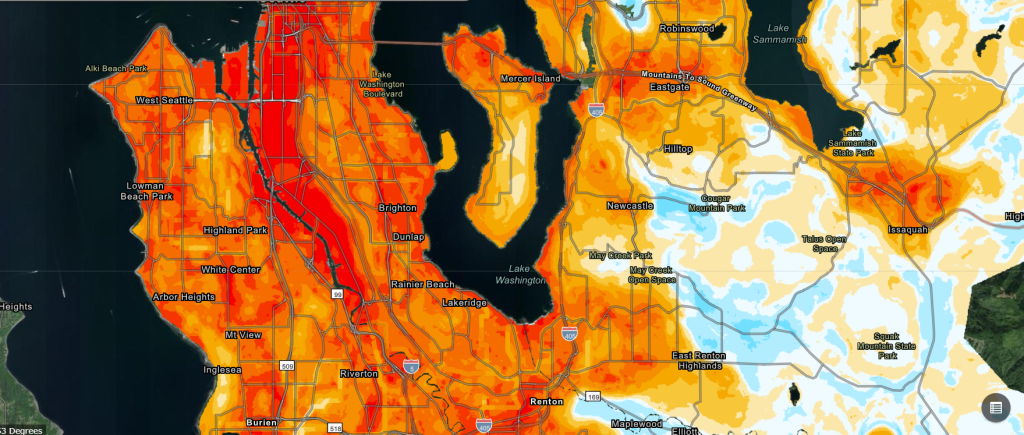

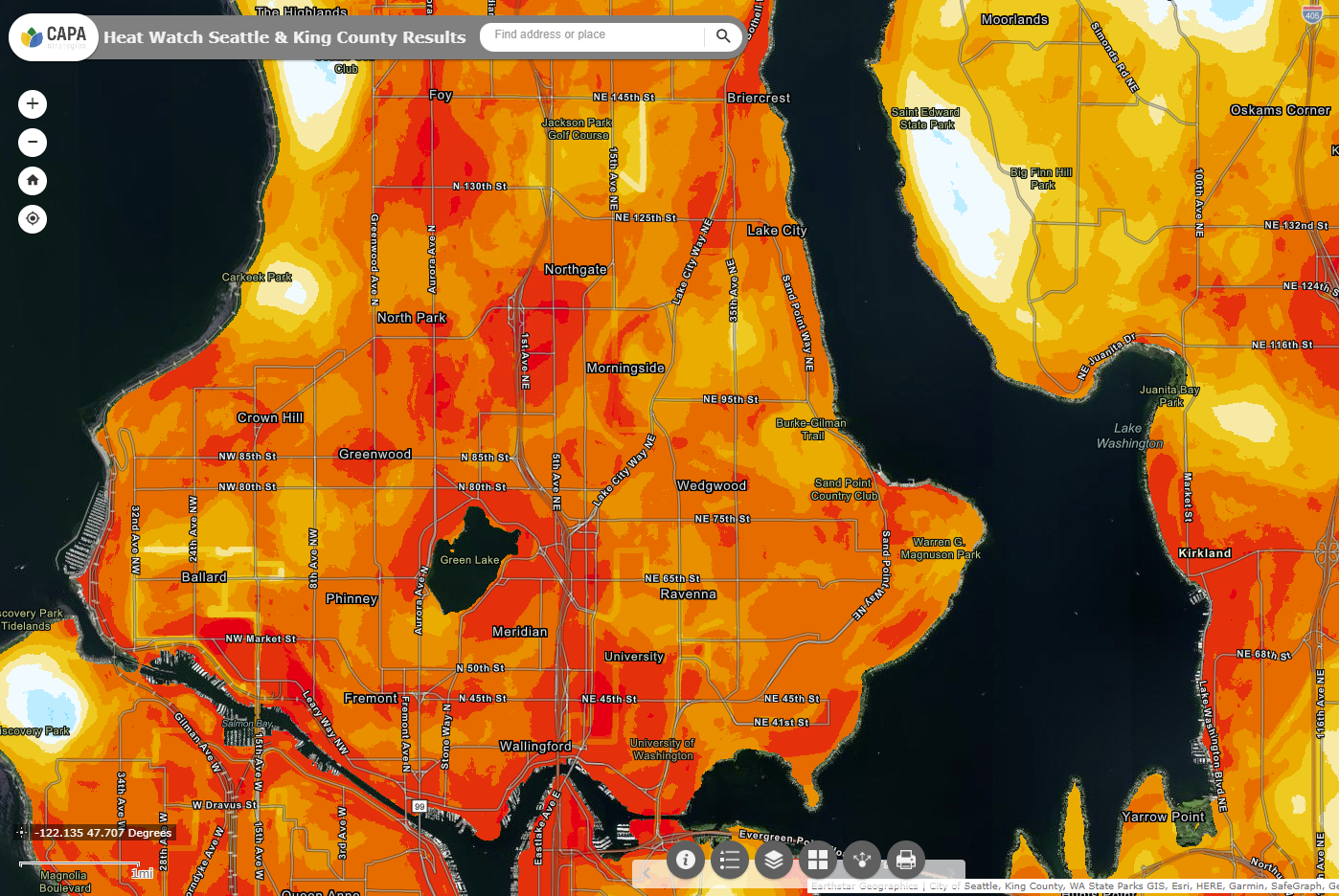

For Seattleites, the recent heat wave brought into stark relief areas of the city lacking adequate tree cover and shade and underscored the resilience of streets that have sufficient canopy. Conversely, it showed how parts of the city with wide expanses of pavement and concrete trap more heat. Ashli Blow demonstrated this point with a video accompanying her street tree article in The Urbanist, which showed how her thermometer went up as she biked from shady tree-covered areas to more pavement-heavy parts of town.

Highways and interstates were some of the biggest heat magnifiers of all, and it’s important to point out that all the vehicles on busy roads contribute heat of their own. On the other hand, large stands of forest like Discovery Park, Carkeek Park, and Washington Park Arboretum barely show up in heat maps and offer relative comfort to people walking and biking during high temperatures.

In so many ways, our transportation infrastructure is climate infrastructure, but right now it’s exacerbating the problems we face related to the climate crisis instead of mitigating and adapting to them. A quarter of Seattle is paved over to move and store cars. All of that asphalt acts both as a heat trap and an impermeable surface directing toxic runoff into waterways and a sewer system ill-equipped to deal with rainstorms that are being souped up by climate change.

Those major rain events mean sewer outflows into Puget Sound which hurt salmon runs, Orcas, and the whole ocean ecosystem. Recent research has confirmed that runoff is toxic to salmon due to tire particles, which troublingly means electric cars will not solve the issue. On the flip side, adding more apartments and denser housing is not increasing road runoff, and it actually can mitigate it thanks to storm retention requirements on new development. Yet, adding more pavement does exacerbate the runoff problem and should be avoided.

If our next transportation levy and comprehensive plan were to prioritize green climate-friendly infrastructure, we’d have to do things quite differently than we do now. Today the way it works is that the City has a few aspirational long-term plans sitting on a shelf, but when it comes to a specific project, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) ultimately listens to what the traffic engineers tell them to do. If a project is projected to negatively impact level-of-service for cars too much, then it’s a no go. That tendency can doom a project as small as a single protected bike lane on a bridge over a freeway, as Seattle recently found out with the case of NE 45th Street.

But for a system that accounts for a quarter of Seattle’s land area, streets should have a higher purpose than simply moving more cars more quickly. If we approached these assets with an open mind, we’d see that greening our roads could be a triple win. Green streets decrease the urban heat island effect, capture more runoff before it hits Puget Sound and kill salmon, and create safer and more pleasant places to move people. Seattle has a goal of reaching 30% tree canopy cover by 2040. Although much of the recent debate has focused on stricter regulations on new apartment developments, public street right-of-ways and single family zones, which have looser requirements for removing and adding trees, hold the key to meeting — and exceeding — that goal.

Going beyond core goals like expanding the safe bike network, adding bus lanes, and making sure bridges don’t collapse, this article will sketch out what a Seattle transportation levy might focus on to carry out a green transformation expanding the city’s tree canopy on publicly owned land.

Adding green boulevards

Let’s start with the big splashy projects Seattle might consider to adapt to climate change. Short of converting golf courses to park use and filling in fairways with trees (and maybe some eco-friendly housing too), carving out new megaparks like Discovery is tricky. However, there are bold greening projects the city could pursue that would have a big impact. Basically, Seattle hasn’t added a properly tree-lined boulevard since the Olmsted park expansion era of the early 20th century. Frankly, that is an indictment of car-centered city planning that has occurred since then.

Every Council District in the city should get at least one new green boulevard that downsizes a currently overly paved one. Below I’ve proposed some potential candidate corridors across the city but certainly more possibilities exist (tweet or email us with your own). A few of these, like Aurora Avenue just last week, The Urbanist has written about before. Some of these corridors can also fill in gaps in the bike network, adding to their benefit. There’s also a good deal of overlap with the frequent bus network so some of the corridors would need to devise a way to provide transit priority as well.

- CD1 candidates: Airport Way S in Georgetown, Fauntleroy Way SW, and 14th Avenue S in South Park

- CD2 candidates: Beacon Avenue S, Wilson Avenue S, and Rainier Avenue S

- CD3 candidates: 12th Avenue, Martin Luther King Jr. Way, Boren Avenue, Yesler Way, and 23rd/24th Avenue

- CD4 candidates: Woodland Park Avenue N, Brooklyn Avenue NE, and Roosevelt Way

- CD5 candidates: Aurora Avenue N, Lake City Way NE, 5th Avenue NE, and N 130th Street

- CD6 candidates: Aurora Avenue N, 15th Avenue NW, and 24th Avenue NW

- CD7 candidates: Alaskan Way and I-5 freeway lid park

Some of the biggest gaps in canopy cover and park and open space access are in diverse working class neighborhoods like the Rainier Valley, White Center, Bitter Lake, and Lake City. Places like these have borne the brunt of racist transportation planning over the years, with their communities targeted for highway expansion (and all the pollution and traffic violence that comes with that) but often skipped over for people-centered investments, like parks, sidewalks, and bike lanes.

My home district, CD4, is lucky to be among the richest in green Olmsted boulevards. One of those, Ravenna Boulevard, provides a good template for what is possible with a design that emphasizes tree canopy and pedestrian comfort. Ravenna ties together Cowen Park and Green Lake Park, providing a continuous shaded, leafy connection from end to end. Because the rows of trees grow in a wide median rather than a small planter box in a sidewalk, they’ve grown quite large over the years and have branched out to provide solid canopy above the entire public right-of-way, which also included flexpost-protected bike lanes along the median. It’s also well-connected to trails in the park system.

Again thanks to Olmsted planning, Green Lake is ringed by a linear park with a pedestrian loop around the lake, which has also been improved upon with recent addition of an outer loop of protected bike lanes that will soon be completed when the final stretch of protected bike lanes is added to close the gap along Aurora Avenue. To the south, Green Lake abuts shady Woodland Park, which means people walking, rolling, or biking can stay out of traffic and the sun for a long stretch. At the south end of Woodland Park, however, conditions get dicey as the canopy cover and safe all-ages-and-abilities biking facilities abruptly end. This makes an ideal spot to add a new facility via our boulevard overhaul, however.

Example: Woodland Park Boulevard

The city’s bike master plan identifies Woodland Park Avenue as a future greenway, but, as far as I can tell, no progress has been made toward achieving that goal. Currently, as a relic of its streetcar days, it’s an overly wide street that resultingly often lacks tree canopy. Some sections are pockmarked with potholes and several intersections have dangerous uncontrolled crossings with speeding cross traffic, particularly at Bridge Way, N 46th Street, and Green Lake Way N. Controlled intersections would need to be added to advance this plan, and in the case of the Bridge Way intersection, I’ve already proposed a simple solution of a four-way stop with sidewalk bumpouts, which likely could work for many similar intersections in the city.

The width of the street allows enough room to put a median down the middle lined with large trees — and if we want to take a page from Mexico City, we could put a pedestrian path down the middle too, which would accentuate the connection to the park system. Turning Woodland Park Avenue into a greenway with safe walking and biking facilities would finally connect the Burke-Gilman Trail to Green Lake and beyond. It closes a gap in the network, while also serving a fast-growing neighborhood that hasn’t seen major upgrades to its transportation infrastructure one would expect when more than 2,000 apartments are added. (And full disclosure, it’s also the street I live on so I’m personally invested.)

With trees down the middle, the tree canopy would be much fuller, storm runoff would be much less, and people walking, rolling, and biking would find a much more pleasant and traffic-calmed space. A similar intervention would likely work for other wide streets like Aurora Avenue, with freight and transit lanes continuing to ensure the street (and other major arterials like it) still meets these two core needs.

Augment street tree program to ensure broader canopy

Many Seattle streets are not wide enough to fit a line of trees down the middle, at least if we plan on maintaining two lanes of car traffic. Some streets like University Way NE (better known as The Ave) make sense for a full pedestrianization which could come with added trees. But as far as Seattle transportation levy projects on the ballot in 2024, prospects may be dim for less vetted pedestrianization transformations. That said, The Urbanist has endorsed Seattle Neighborhood Greenways crowd-sourced list of 130 miles of pedestrianized open streets, which shows lots of candidates are out there.

Streets where full pedestrianization isn’t yet possible can still get major tree cover upgrades by adding curb bump outs, roundabouts, or diverters with large tree wells in them. For this this strategy to excel, though, the City will need to get more aggressive with the trees it plants, selecting larger varieties, and providing them enough soil to thrive.

Arborists sometimes refer to 3 foot by 3 foot planting boxes as tree coffins given how tough it is for a tree to thrive with so little soil, especially when road pollution is also stunting their development. Recently planted trees along Green Lake Way N (near the Lower Woodland soccer fields) include a few saplings that are struggling to hang in there, appearing skinny and scorched by the sun. Perhaps they’ll bounce back, but even if they do that variety also looks unlikely to grow nearly as large as the trees that the Olmsted design included in Green Lake Park just to the north.

We should be thinking bigger and finding places to plant the giant trees that used to dominate Seattle’s landscape before White settlement. Trees that used to dominate coastal forests before Seattle was carved out of those forests include Douglas firs, Western hemlocks, Sitka spruce and Western red cedars, the latter of which was revered by the tribes of Northwest, with Salish names referring to it as “mother” and “long-life-giver.” But it’s also not always practical to work trees that grow this large into roadways, considering what roots can do to sidewalks and pavement. Sometimes faster growing trees may make sense as well to ensure we can get our canopy expanded ahead of a warming climate.

To stay ahead of climate change we should planting aggressively everywhere we can and including trees that grow large and cast a lot of shade for people walking, rolling, biking or lounging underneath. While it’s inevitable squabbles over repurposed parking and lost general purpose driving lanes will crop up, I suspect most Seattleites would welcome a greener Emerald City.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.