The state treasurer’s office brought some bad news to the Washington Transportation Commission this week regarding the revenue forecast for the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) SR 99 tunnel underneath downtown Seattle. Given current trends, the financial models predict that the SR 99 tunnel won’t be able to financially sustain itself in the near term, and that trend isn’t expected to reverse itself over the long term. “We’re seeing a permanent reduction in revenues that ranges from 16% on out to over 30% [from year to year],” Jason Richter, the state’s Deputy Treasurer for Debt Management, told the commission that sets the state’s toll rates.

Richter didn’t sugar coat the outlook for the toll facility remaining in the black. “I think it’s important to note that there’s been a permanent shift in the projected use of this corridor, which is going to have a pretty substantial negative impact on our revenues over the projection period” which extends to 2052, he said. “We’ve just got a sea of red…we’ve got insufficient revenues in every year during the projection period essentially, and a lot of them are pretty substantial.” He provided the commission a balance sheet that by 2052 showed a cumulative negative balance of $236 million dollars.

“There’s going to need to be some additional toll increases, but I’m suspicious that that’s not going to be sufficient to cover the entirety of this issue, given that the shortfall in a lot of years is equal to roughly a third of the revenue coming in,” he said. “There’s likely going to be a need for some legislative assistance on this…all of the potential actions will be needed to remedy this particular problem.” Raising toll rates to make up for declining revenues is a standard practice, but it can’t work if those toll increases drive people away, and the SR 99 is a route that’s pretty easy to avoid for a lot of people.

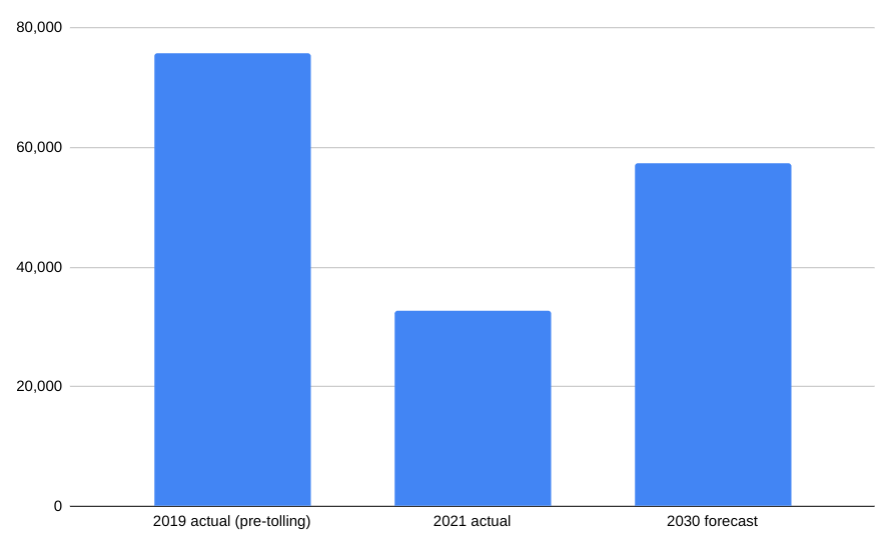

Overall traffic volumes in the SR 99 tunnel are not looking good compared to the forecasts that WSDOT prepared over a decade ago as part of the environmental review for the Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement program. That documentation projected that with tolling in place, by 2030 over 57,000 vehicles per day would use the facility, a substantial decline compared to the number that would use it if it weren’t tolled.

That 2030 forecast is lower than the actual volumes the highway saw in 2019, before tolling was implemented and prior to the impact of the pandemic on traffic volumes. But now traffic volumes are well below 40,000 per day: numbers from last year show slightly more than 32,000 vehicles per day, and WSDOT’s volume dashboard shows that volumes on the corridor have been consistently 30-40% below their pre-pandemic levels even as other state highways are essentially back to pre-pandemic traffic volumes.

But that 2030 forecast comes with a big caveat: it assumed much higher tolls than are currently in place. Southbound PM peak tolls of $5.00 in 2015 dollars, or $6.25 today, were used to project those volumes. With a Good To Go pass, the highest tolls get today is $2.70. Raising tolls would likely push additional users out of the tunnel, not helping the revenue spiral.

Between 2019 and 2022, the legislature loaned the SR 99 toll program several million dollars to keep the program stable following the dip in traffic volumes during the pandemic. But payments on the debt issued to pay for the tunnel and costs to operate and maintain the tunnel are gobbling up a larger and larger share of the projected revenues generated from tolling. In 2020, with the substantial decline in usage of the tunnel, the program did not have enough revenue to cover costs; that’s projected to also be true in 2022. And those loans from the legislature will ultimately be repaid, of which Richter said “there’s not a solid plan in place for when that’s to be.”

This year, the legislature contemplated spending nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars removing all tolls from the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, where toll revenues had been assumed to pay for an abnormally high share of the overall project when it was built. Ultimately, a much less dramatic fix was passed that is intended to lower toll rates quite modestly. But the entire episode illustrates just how volatile WSDOT’s tolled corridors, most of which are used by the state as revenue generators and not demand management tools, are. The Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which has few alternatives, has essentially fully recovered from its pandemic volume lull and that associated revenue hit. Things don’t look anywhere near as rosy for SR 99.

In addition to the latest forecast, the long-term traffic volume trends in the SR 99 tunnel could be even less stable than they appear now. Within a year, the new Elliott Way roadway will open, providing a new direct route between the 15th Ave W corridor through Ballard and the waterfront, creating an attractive alternative for a lot of drivers who may currently be using the tunnel. Of course, the 99 tunnel always becomes more attractive when alternate routes become congested, which may happen over time.

Contacted about the new dire revenue forecast, WSDOT spokesperson Christopher Foster didn’t provide much additional information. “The traffic and revenue information shared at [Wednesday’s] Washington State Transportation Commission (WSTC) meeting is based on current traffic and revenue forecasts. These forecasts are updated on a quarterly basis and are subject to further changes. We’ll continue to work with our partners at the Washington State Transportation Commission and the Office of the State Treasurer (OST) to evaluate the pandemic’s effect on traffic in the SR 99 tunnel, and strategies for meeting financial needs for the facility,” he said.

Setting the SR 99 toll program up to pay back the bonds that were issued to pay for the tunnel itself may not be that uncommon of a practice for transportation departments, but it is the exactly sort of thing that tunnel skeptics were raising alarms about back when the future of the Alaskan Way Viaduct was being debated. In 2009, Mayoral candidate Mike McGinn raised concerns about Seattle residents being on the hook for any cost overruns from the project, concerns he brought into the Mayor’s office when elected even as he ultimately proved unable to stop the project. Now, shortfalls in the tolling program could ultimately end up making all Washington residents pay, if the tunnel needs a bailout.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.