Kenmore is moving forward with parts of its 2024 Comprehensive Plan update, which will look out to 2044. A suite of proposed policy changes around land use, housing, and capital facilities are expected to be vetted by the city council over the summer and could be adopted this fall. At the same time, the city is entertaining a package of missing middle housing code amendments that could allow for more duplexes and triplexes to be built in the city.

Through 2044, Kenmore is expected to grow by 3,070 housing units and 3,200 jobs. However, a midterm check-in of the 2035 planning horizon showed that Kenmore failed to keep pace with expected growth, achieving only 67% of the targeted new housing units (1,120 housing units) and -73% of new jobs (-1,050 jobs) by 2018.

The city’s long-standing restrictive zoning regulations that favor single-family detached housing and virtually nothing else are a very likely contributor to this; limited housing stock has pushed the city’s average home cost above $1 million. Of Kenmore’s total acreage, about 80% of the city is composed of single-family and public/open space land uses whereas multifamily (about 5%), commercial (about 3%), and industrial (about 1.5%) land uses make up very small shares.

Kenmore has made some progress in reforming its zoning regulations in recent years. The city modestly liberalized zoning regulations in 2020 to encourage more accessory dwelling units (particularly detached accessory dwelling units) in the city’s vast single-family areas.

In terms of updated comprehensive plan policies, Kenmore is proposing some interesting ideas in the following areas:

- Increasing commercial opportunities by directing the city to consider and support:

- Small-scale, neighborhood commercial uses that meet the daily needs of residents and are located within a walking or biking distance of homes;

- Small-scale, pedestrian-oriented commercial uses adjacent to trails that specifically serve the needs of trail users; and

- Home-based businesses as a way to keep jobs closer to home.

- Adding special study areas for intensive urban development opportunities, including:

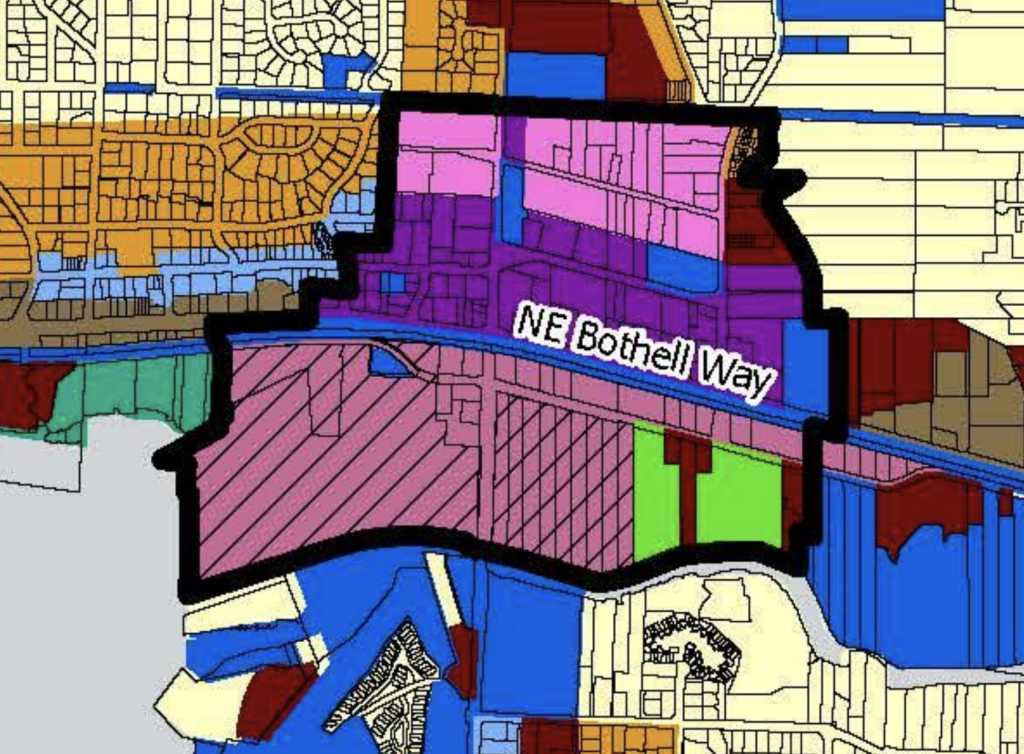

- Lakepointe (a large site on Lake Washington and adjacent to the Sammamish River) as a mixed-use, pedestrian-oriented district with some affordable housing. Policy priorities include design standards, sustainable development strategies, minimal surface parking, public access to waterways and open space, bike connections to Downtown Kenmore and Burke-Gilman Trail, and transit connections.

- Glacier Northwest (a large site near the Sammamish River and off NE 175th Street) as a mixed-use, pedestrian-oriented district with some affordable housing. Policy priorities are largely the same as Lakepointe.

- Housing policies that the city is pushing for include calls for more renters’ rights, affordable housing, and residential densities in certain cases. The policies call for:

- Implementation of tenant protections that increase housing stability, such as rent increase notices and just cause eviction requirements;

- In the Downtown area, inclusion of requirements for affordable housing in higher density residential and mixed-use developments;

- As part of rezones that increase development capacity, consideration of affordability requirements;

- Allowing more diverse housing, specifically duplexes and triplexes (missing middle housing) in low-density residential areas within a quarter-mile of major transit corridors;

- Concentration of transit-oriented development opportunities at the Kenmore Park-and-Ride site on SR 522 with high densities and affordable housing requirements; and

- Consideration of changes to regulatory requirements to encourage low- and medium-income housing, such as reduced parking mandates, building code innovations, expansion of the Multi-Family Tax Exemption (MFTE) program, and actions that reduce development costs.

Additionally, Kenmore is planning to pursue designation of the city center as “Countywide Growth Center,” which would raise its prominence in King County and the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC). An adopted framework by the PSRC, allows for counties to recognize Countywide Growth Centers if an area meets certain eligibility criteria, such as achieving minimum existing density of housing and job requirements, planning for higher densities, and supporting them with multi-modal transportation options. The Countywide Growth Center is intended to cover much of Kenmore’s city center, but it will need the approval from King County and map designation by PSRC.

The proposed comprehensive plan amendments, however, are cautious about growth and explicitly call for “an incremental approach to expanding medium density housing opportunities in the city.” Staff have also retreated from a proposal to extend the Tolt Pipeline Trail about 1,000 feet via Swamp Creek over a handful of community concerns related to limited wetland impacts. Without the extension, people walking, rolling, and biking have to deviate about a mile to reach the trail on narrow, dangerous streets — some without any sidewalks and zero bike lanes.

Kenmore’s proposed missing middle housing changes

So what exactly are in the proposed missing middle housing code amendments? Here’s a list of the changes under consideration.

| Development Standard Change | Proposed Regulation |

| Definition of “multiple-family dwelling” | Clarifies that this includes “duplexes” (two dwelling units in a residential structure) and “triplexes” (three dwelling units in a residential structure) that are not a townhouse but removes “apartments” and “townhouses” |

| Definition of “townhouse” | Clarifies that this is a row of two or more similar attached dwelling units with each unit owned independently |

| R-6 zone | Adds a new section that the R-6 zone allows for single detached dwellings units and in some areas duplexes and triplexes |

| Townhouses when allowed | Revises provisions that townhouses may be allowed through binding site plan when obtaining an conditional use permit |

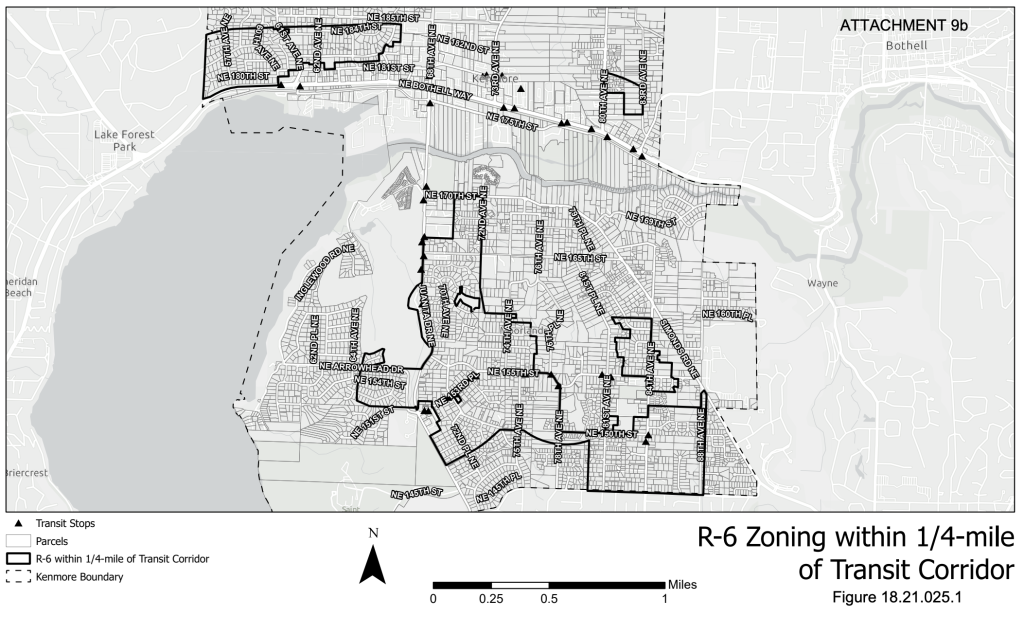

| Duplexes and triplexes when allowed | Adds that duplexes and triplexes are only allowed in R-6 zones when located within a quarter-mile of frequent transit, but only on lots that are fully within such an area (see map below) and meet prescribed lot sizes |

| Density limits | 22 to 24 dwelling units per acre for duplexes and 26 to 29 dwelling units per acre for triplexes (townhouses are limited to 1 to 9 dwelling units per acre, depending upon zone) |

| Minimum lot size requirements | Side-by-side duplexes: 50 feet wide and 100 feet deep; stacked duplexes: 40 feet wide and 100 feet deep; and triplexes: 50 feet wide and 100 feet deep |

| Height limits | 30 feet (or 2.5 stories), but no more than 24 feet to the eaves for duplexes and triplexes |

| Building dimension limits | Generally, maximum facade widths ranging from 22 feet to 50 feet, depending upon use type and lot width, and maximum facade lengths ranging from 40 feet to 60 feet, depending upon use type and lot depth |

| Design standards | Duplex and triplex buildings oriented toward the street, preference for street-oriented dwelling unit entrances, preference for garage entrances to be located out of view of the street, and limits on surface parking with preferences to screen and hide |

| Parking and driveways | For duplexes and triplexes, 0.75 car parking spaces per dwelling unit required, and driveways must be a minimum of 35 feet in length from street to garage and 20 feet in length to parking areas and 10 to 12 feet wide |

Other developments standards that apply in the R-6 zone will also apply to duplexes and triplexes, such as setbacks (15 feet from the street, 20 feet from rear lot lines, and 15 feet total for sides) and 60% to 70% impervious surface coverage maximums.

During last month’s joint city council and planning commission meeting, Lauri Anderson, a principal planner for the city, outlined the estimated number of new missing middle housing units expected from the draft legislation, which really isn’t anticipated to be that much.

“We did a rough analysis and we did that based on the land within the quarter-mile area that had already been identified as either vacant or redevelopable removing critical areas and their buffers,” she said. “The capacity for duplexes and triplexes was around 300 units each, however, that’s if every single parcel redeveloped — and that’s not what has historically been seen. So if you assume 25% of those parcels developed, then we end up with about 40 duplexes and 32 triplexes.”

Kenmore claims that it has sufficient development capacity for housing and jobs, but that’s heavily predicated on a handful of industrial and commercial properties as well as a string of very pricey single-family waterview properties redeveloping and one-off rezones over the plan period. As noted before, areas zoned for multifamily housing in the city are minuscule and most of them have been built out. Additionally, single-family areas have also been mostly built out, further restricting future development capacity. Nevertheless, the city claims that they have residential capacity of 4,135 homes — a surplus of 1,065 homes — and employment capacity of 3,881 jobs — a surplus of 681 jobs through 2044.

During the June meeting, Kenmore Mayor Nigel Herbig argued that the Kenmore needs to go beyond just a limited expansion of allowing some missing middle housing types as part of the comprehensive plan update.

“The housing crisis in this region is affecting everybody all levels, except at the very top. We both need to building more market-rate housing and subsidized affordable housing,” he said. “Even if a townhome is being sold for $800,000, that’s a heckuva lot cheaper than any of the houses I’ve seen being listed in Kenmore in the last six months. Everything seems to be $1-$1.2-$1.4-$1.5 million and these are just 70s ranch houses going a $1.2 million, it’s insane.”

Herbig also illustrated how low-density zoning can cause environmental harm by driving growth to the edge of the urban growth area (UGA) and also drive up costs.

“I really view housing as almost one of the more important environmental issues we deal with because as we’ve seen over the last 50 years as most cities in the Puget Sound region have protected exclusionary single-family zoning, it has forced a lot of development to further and further out towards the urban growth boundary,” he said. “Not only does that drive up costs, it also forces people to move further away from work, further away from the urban core, which leads to longer commutes, increased traffic… I would argue that a new single-family development out on a greenfield at the edge of the UGA has a larger impact on the regional environment than focusing our development in the urban core or closer to the urban core at least.”

Getting into the weeds of the proposed missing middle code amendments, Herbig raised several interesting points. He said that he supported the proposed lower parking requirements for missing middle housing, but could support even lower parking requirements, felt that missing middle housing building height limits shouldn’t be any more restrictive than single-family homes, and believed that tree requirements should be equitable between missing middle housing and single-family family homes.

Other Kenmore councilmembers raised similar issues to Herbig, which suggests that the city council may be prepared to go further than staff and the planning commission in allowing missing middle housing and updating the comprehensive plan.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.