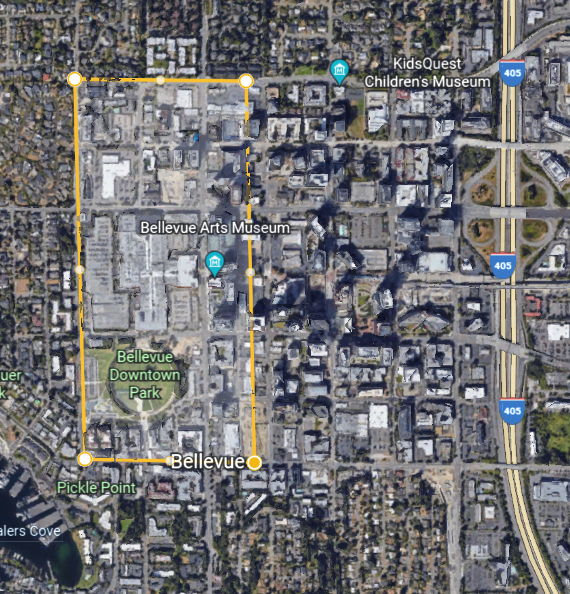

During my research and writing of the Downtown Bellevue development articles, I actively estimated the amount of parking spaces that Bellevue had recently added and could add as part of its development boom. Accustomed to Seattle’s parking ratios, my original estimate was that around 10,000 parking spaces would be added as a result of these new developments. However with a growing understanding of the scope of the growth, the city’s parking regulations, and developer complicity, my estimates rapidly climbed. I was aghast, as my projections grew to 15,000, 20,000, 25,000, and then somewhere under 40,000. After landing on some more final numbers and summing up those figures, it was clear that a total of over 43,300 parking spaces have been constructed recently, are under construction, and in permitting in Bellevue. Over 8,000 parking spaces had already been built since 2018.

The feeling of horror quickly evolved into frustration. If we assume a parking space is 8 feet by 18 feet, then 43,300 parking stalls would take up around a quarter of a square mile. That’s roughly a third of Downtown Bellevue’s land area, which is not even counting the drive lanes in the parking garages. These figures will have devastating impacts on our region’s climate aspirations. Having suppressed myself over the past three Bellevue development articles, I’m ready to channel my exasperation in this piece. Bellevue’s disregard for parking impacts rises beyond climate denial. It’s unadulterated climate arson.

Bellevue’s core climate change goal is to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 80%, compared to a 2011 baseline, in 2050. Relevant to parking, it’s partially trying to accomplish this goal through electric vehicle (EV) adoption, fuel efficiency, and mobility and land use strategies that include transit access and reductions in VMT. Clear red flags emerge for these goals, especially when tens of thousands of new parking stalls could be greenlit in the next few years.

More parking = more cars

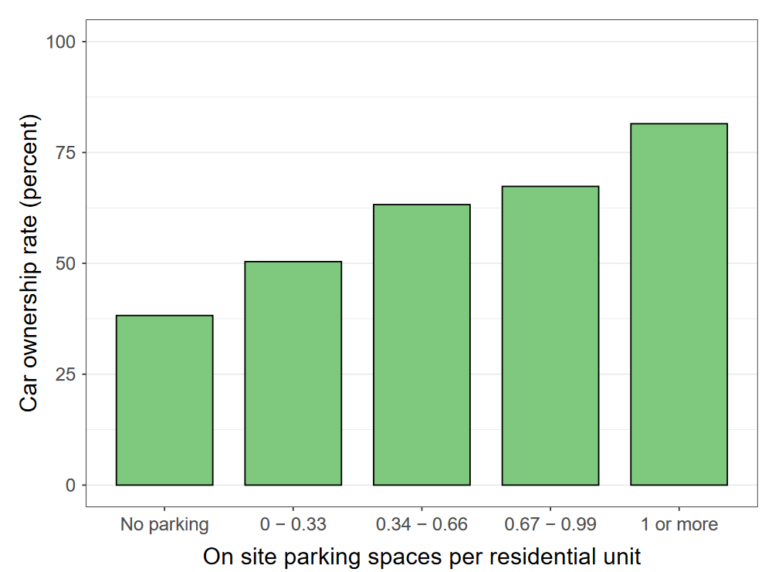

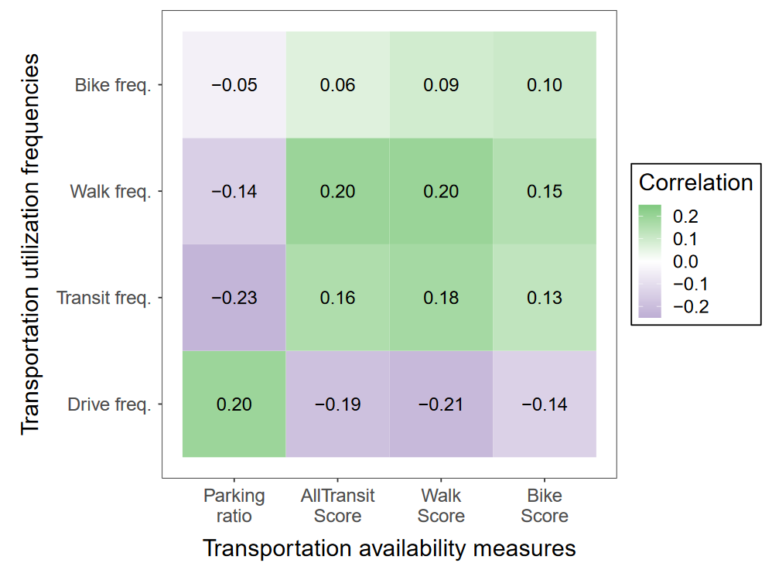

In a 2021 study, Adam Millard, Jeremy West, Nazanin Rezaei, and Garima Desai were able to establish a link between the availability of parking with vehicle ownership and transportation mode decision making. They found that higher rates of available parking per unit increased car ownership. A higher parking ratio was also positively correlated with driving frequency and negatively correlated with biking, transit use, and walking.

Graphics from the study visualizing the relationship between parking ratios, car ownership, and transportation utilization. (Courtesy of Adam Millard, Jeremy West, Nazanin Rezaei, and Garima Desai)

In terms of what has been built in Downtown Bellevue since 2018, the vast majority of residential projects support parking ratios greater than one stall per unit. This ratio decreases in projects currently in permitting, but the majority are still proposing greater than .66 stalls per unit. Thus, Bellevue is setting up its Downtown to be even more car burdened.

Cars are the problem

A dependence on electric vehicles is the folly of climate strategies that focus on greenhouse gas emission reduction in many localities. By focusing on the electrification of vehicles, Bellevue’s strategy fails to take into account the embodied carbon that electric car production involves. Embodied carbon often refers to emissions generated by resource extraction, manufacturing, transportation, and other processes involved in the supply chain. While figures will vary, it is generally understood that the manufacturing electric cars is more carbon intensive than their combustion engine counterparts because the energy intensive production process for lithium-ion batteries.

Focusing on fuel combustion allows for Bellevue to ignore this embodied carbon. Undoubtedly, lifetime carbon costs of EVs are lower than their gas-guzzling counterparts. However, such a benefit becomes trivial when tens of thousands of new parking stalls increase car ownership and harm greener options like walking and biking.

Additionally, even if electric cars aren’t producing GHG emissions they will still have their impact on Bellevue’s ecosystem and built environment. As Brandon Zuo reported for The Urbanist, tires currently contain a preservative known as 6PPD that produces a substance toxic to salmon and other wildlife when it reacts with ozone. Zuo also cites a study that found that EVs and gas-power vehicles emit similar amounts of fine particulates, which are also harmful to people. Once again, greater car use and parking also exacerbate this issue.

Bellevue’s role

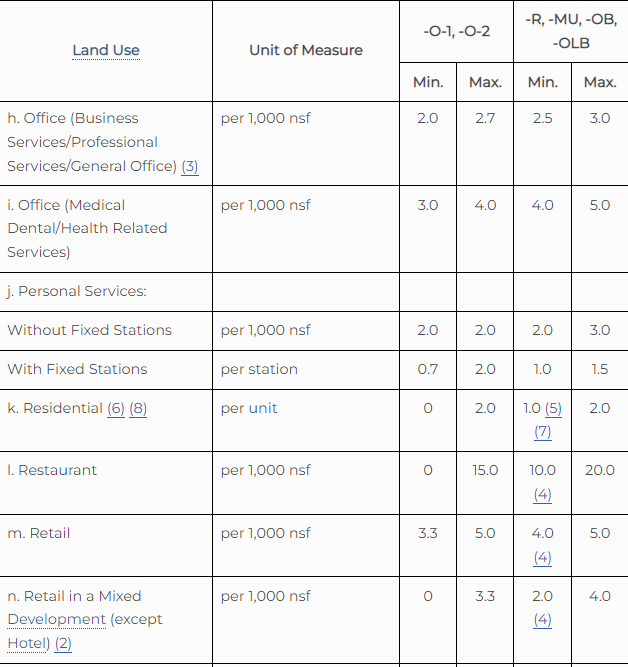

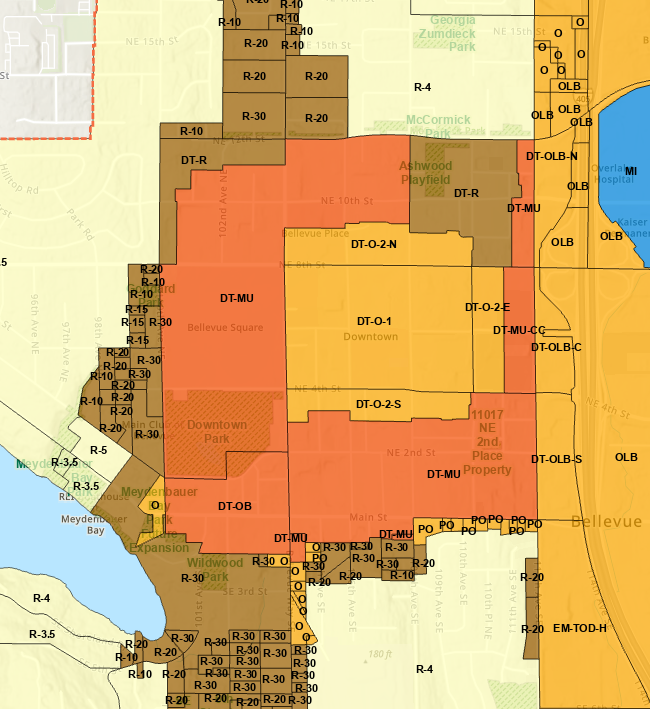

I have yet to mention the primary contributor to Bellevue’s parking problem, office towers. To explain this phenomenon, it’s best to look at the parking regulations in Downtown Bellevue. For parking, the downtown zones are split into two categories, the central office/O zones and everything else, which includes additional office, mixed-used, and residential zones. The most central office zones do have slightly lower parking ratio requirements than other office zones, and residential development included in these zones is also more modest, but in general the parking ratios are high in Downtown Bellevue.

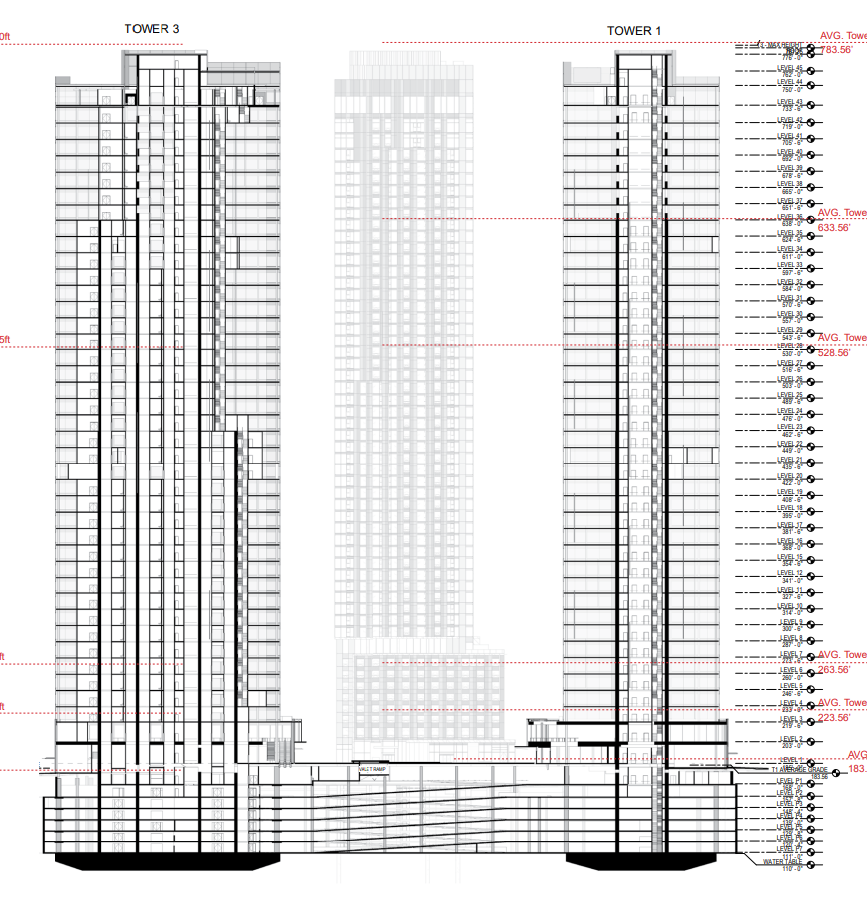

With 16+ million square feet of office space proposed, the lowest minimum office ratio produces 32,000+ parking spaces. One to one, 13,000 residential units produce 13,000 parking spaces. These ratios are so great that many developers are seeking deviations to reduce the required parking in their projects. The Cloudvue project is seeking to produce 2,487 stalls, which is actually lower than their minimum required parking at 2,774 stalls. The maximum parking ratio would allow them to construct over 4,000 stalls.

Even with the years of knowing that light rail coming to Downtown, the City of Bellevue is still allowing these absurd parking ratios. It seems determined to support and worsen sprawl with proposed office space overwhelming proposed residential units, forcing, and even incentivizing, workers to commute by car by offering plentiful parking while also strangling housing options near where they work with restrictive zoning.

The City’s climate goals seem engineered to ignore the problems that its parking policy is creating. As a result, I’m almost glad that the city has failed to upzone South Bellevue light rail station. At least they’re not yet replicating this disaster there.

Bellevue could make a concerted effort to improve their travesty of a climate plan, and the first step would be to drastically reduce its parking maximums in new developments. Considering how lacking Bellevue’s pedestrian, bike, and transit infrastructure is, there is much room for improvement.

Wider sidewalks, traffic calming, friendly signaling, more bike lanes, more frequent bus routes, a more complete transit network, a streetcar, anything would go a long way to tackling the city’s car obsession. Studying, encouraging, incentivizing, and mandating parking garage conversion so these structures can be used more productively might be able to resolve the existence of parking garages that will be around for many decades to come. Turn those parking spots into data centers or storage space, anything Bellevue — just do something to live up to your climate aspirations.

Shaun Kuo is a junior editor at The Urbanist and a recent graduate from the UW Tacoma Master of Arts in Community Planning. He is a urban planner at the Puget Sound Regional Council and a Seattle native that has lived in Wallingford, Northgate, and Lake Forest Park. He enjoys exploring the city by bus and foot.