In 2021, King County Executive Dow Constantine declared gun violence a public health emergency, allowing for the County to increase its investment in public health strategies to curb shootings. Since then, groups like the King County Regional Peacekeepers Collective have scaled up their efforts, even receiving attention from the White House for their holistic, regional approach to the problem. But while staff have reported signs that progress may lay ahead, in a recent presentation for the Seattle City Council, they also acknowledged that the increase in shootings in King County that began in 2021 shows no sign of abating.

Meanwhile, the types of gun violence incidents have become more diverse, raising the question of how to create and invest in new programs and services.

The gun violence that erupted across Seattle last Sunday, June 10th, provides an example of the complexity of challenge faced by public health workers, law enforcement, and local officials. According to the Seattle Police Department (SPD) Blotter, early in the morning, approximately 30 shots were fired and a 14 year-old was injured in Lake City. Two AR-15 rifles with 50 rounds of ammunition were discovered at the scene of the shooting. By the end of the day, SPD would respond to a shooting in Ballard in which no one was reported injured, a shooting in Rainier Beach in which a woman sustained gunshot wounds to her leg and torso, and finally over 50 shots fired both in and near a concert by rappers D.B. Boutabag and Capolow at Washington Hall in the Central District.

While no shooting victims were reported at the final incident, a surprisingly positive outcome given the number of concert-goers at the venue, two attendees were injured during the crowd’s rush to flee the building. Only the night before in the Chinatown-International District, a would-be customer, upset that a pizza shop had closed for the evening, fired 10 shots into the restaurant from a handgun, damaging the business’s windows, but fortunately not injuring any employees or customers before leaving the scene.

Widespread in their geography, type, and the damage they inflicted, the incidents represent the far-reaching impact of gun violence in King County today.

As is often the case, in the majority of the incidents described above, very few or no suspected perpetrators were appended by law enforcement. Public health researchers believe that the low rate at which gun violence crimes, especially nonlethal incidents, are resolved produces a source of stress and fear for many victims and the people close to them.

As result, people may be provoked to purchase or begin carrying firearms themselves, or as a worst-case scenario, instigate reprisal attacks against suspected perpetrators, thus continuing the cycle of violence.

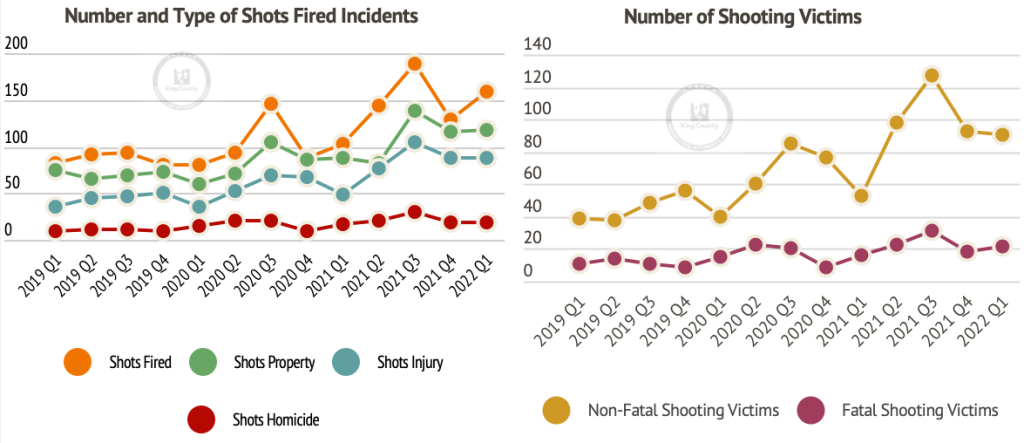

In King County, the numbers have not yet been tallied for 2022, but a preliminary review points towards a continuation of the troubling gun violence trends established in 2021, a year in which the number of shots fired and shooting victims increased by 54% and 70%, respectively, over the four-year average of 2017-2020. Looking closer at victims, the number of nonfatal shooting victims increased by 75%, while fatal shooting victims were also up by 54% in 2021.

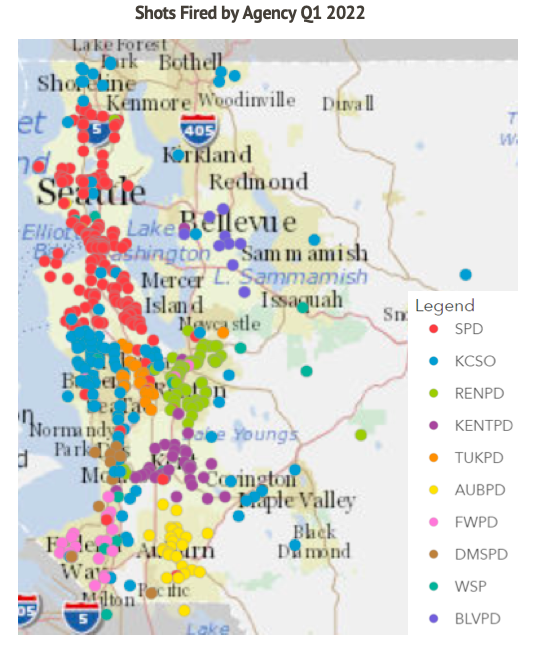

The preliminary tally of the first quarter of 2022 shows 22 people were killed and 91 people were injured in King County, while 384 shots were estimated to have been fired. While these numbers have not reached the heights of the third quarter of 2021, they are still above the average for the past five quarters of data. These shootings do not include suicides, confirmed self-inflicted shootings, or officer involved shootings.

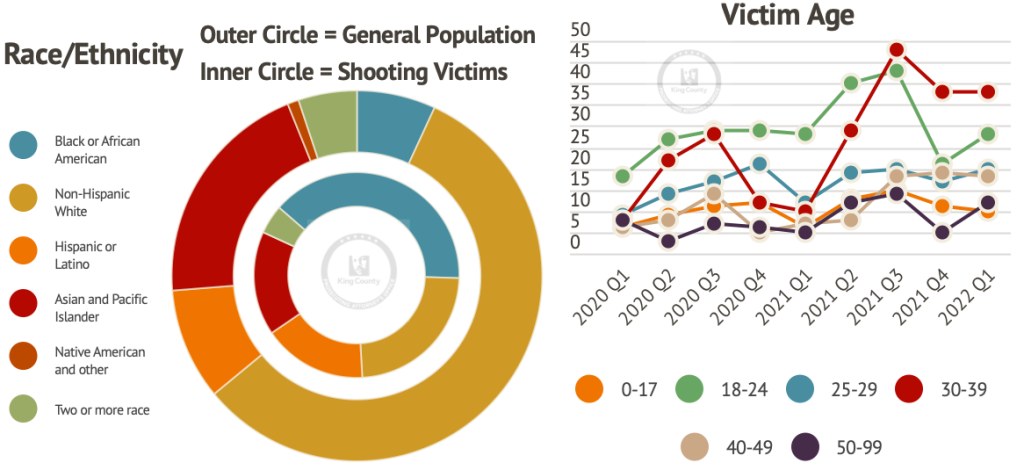

In terms of demographics, data shows that during the first quarter of 2022, 90% of shooting victims were male and 79% identified as people of color, with Black men the group most likely to be impacted.

“Sometimes [data] can be perceived as harming folks so we took an approach to looking at the data in a clearer way, leading with racial equity as we deconstructed the messages we were finding in the data, but with an indisputable sense of clarity that disproportionately Black and brown men are impacted by gun violence both in our region and across the nation,” Lisch said.

In his opening remarks, Dennis Worsham, interim director of King County Public Health echoed the need to be mindful of racial disproportionality in impacts when considering gun violence. “From an equity perspective, it is becoming a leading cause of death for young Black men in our community, and it’s not acceptable. We do need to do the work that needs to happen from a public health approach, but also with community partners, law enforcement, and other electeds,” he said.

According to data from Harborview Medical Center, the regional trauma center, 100-150 young people between the ages of 16-24 years of age are seen in the emergency room in King County for a gun related injury each year. Using this data and comparing it with data from the King County Court Prosecutor’s office, public health workers identified a group of high risk youth as the priority population for gun violence outreach services. Recent trends, however, are complicating that approach.

“The priority population served has dropped lower [age] 12, and it can’t be associated with a specific age,” Lisch said. “It also rises to [ages] 30-39, but no service are provided at this time for this population’s needs.” For the last three quarters, the number of shooting victims aged 30-39 has exceeded those in the 18-24 year-old group.

Lisch explained that most gun violence programs are targeted to youth and young adults, and because of restrictions related to funding, they cannot necessarily provide services to people who fall outside of that age range. Additionally, Lisch explained that the types of incidents have become more varied in recent years with shootings at homeless encampments, domestic violence disputes, and suicides making up a rising share of gun violence in King County.

“Organizations that provide services to young people don’t really address this, so there’s truly an opportunity to scale up and grow,” Lisch said.

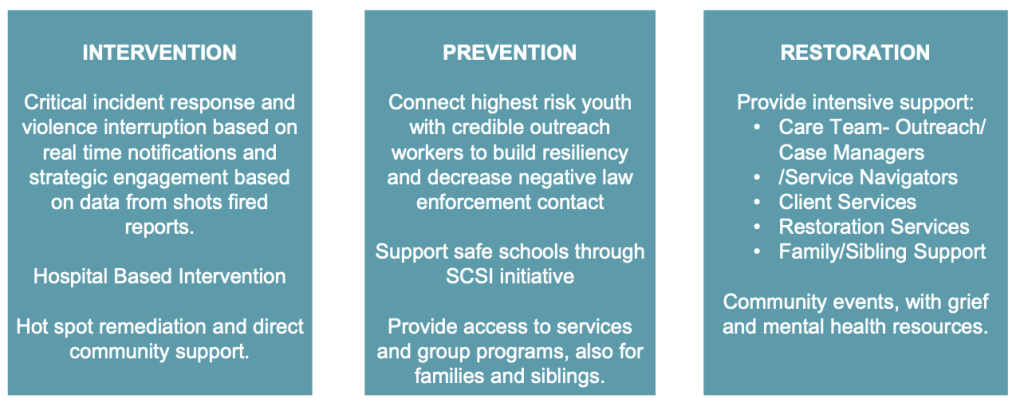

What could this growth look like? For starters, it would mean building on the public health strategies that King County and its partner organizations are already engaging in. The current framework used by King County is divided into three major categories: intervention, prevention, and restoration.

In terms of intervention, hospital-based interventions, or meeting with shooting victims while still in the emergency room, appears to be proving effective. While Lisch acknowledged that they had not gathered the hard data yet on the success of hospital-based interventions, she estimates that 75% of victims who are met bedside end up engaging with services — a percentage that drops steeply when the services are offered at a later date.

Hot spot interventions are another strategy that is being undertaken, although Lisch clarified that it falls more under the banner of a law enforcement than a public health strategy. While hot spot efforts are often associated with scaling up policing in small geographic areas that are associated with higher levels of criminal activity, they may also include environmental changes to an area, such as improving lighting or removing debris, that are intended to make people feel safer.

Councilmember Lisa Herbold (District 1 – West Seattle), who had organized the meeting with King County Public Health, expressed interest in this strategy. “As elected there is not a lot we can do beyond investing in programs, and I want to learn more about the assessment of physical conditions are how we can support the changes needed,” Herbold said.

As a whole, Worsham explained that King County’s preference is to engage in preventative efforts. “From a public health approach we are looking at both down and upstream factors. Ideally the question is not how do we interrupt the violence now, but how do we get at more upstream factors so we don’t even have to interrupt it,” he said.

In the meantime, however, King County Public Health is also looking at how to improve its intervention and restoration services. “Our vision is to build a new kind of public health worker — a first responder like others,” Lisch said. In her description, such a first responder would be able to be a the scene of a shooting quickly, similar to an EMT, and offer trauma-informed and culturally appropriate support to victims.

To continue to scale up these efforts, more funding will be needed. President Biden’s recent executive actions related to reducing gun violence may provide possible sources of grant funding in addition to contributions from the city, county, state level. Last year, the King County Regional Peace Keepers Collective received approximately $2 million from the City of Seattle and $7 million from King County.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.