A policing drama from the creators of “The Wire” and “Treme” is a devastating look at urban policy.

The police aren’t coming, and we know why. Whether your call is to the door of a school massacre or to your home during a catalytic converter theft, the police don’t owe you protection. The department is not designed to serve your needs. Seattle learned a new term for it this week: Z-disposition protocol. It’s for all the calls that are dropped because the best funded police department in the city’s history doesn’t have the disposition to attend them.

Of course, art best illustrates the problem.

“We Own This City” is a devastating look at Baltimore City’s rogue Gun Trace Task Force from producers David Simon (The Wire) and George Pelicanos (The Deuce) available to watch on HBO. Starring Jon Bernthal and Wunmi Mosaku, the show follows a half dozen police officers as they take wads of money from arrestees, beat and torture suspects, and pick up narcotics to deal themselves. Based on the book by Baltimore Sun reporter Justin Fenton, the show is six episodes of breathtaking corruption and perpetual self-justification. The plain clothes police detail was not just robbing the folks they were supposed to protect but also creating an environment where crimes were able to continue with them at the center.

As a Baltimorean by birth and Orioles fan by the hand of a fiendish God, I found the show difficult to watch. “We Own This City” is amazingly acted, tremendously written, and confirmation of everything people leave the city to avoid. There’s little correct things the show does like the proper pronunciation of the word “ambulance” and blocks of empty rowhomes awash in blue police lights. The number of Under Armor shirts was appropriately overwhelming as was the sound of glass breaking on a sidewalk. The details add to the tearfully concussive gut punch of realizing we never even had a chance.

Divisions everywhere

“We Own This City” is both two years late and ten years early. Decades of difficult advocacy by Black communities built up to even mentioning the hard portions of this show on television. Unfortunately, that moment may have passed. Now, slowing police work will be used against anyone not in a red MAGA hat as a soft on crime wedge issue. The same U.S. Senator that put many Black men in jail is going to be held to task as President for a bump in crime because police are uncomfortable learning the Constitution. And this generation in uniform have little incentive to change.

Besides obstinance, why is that change so hard to make? There are two bits of Baltimore marginalia that the show doesn’t delve into which may help us understand. First, Baltimore’s police department is not a city entity. It’s a state agency, set up in the mid-1800s when the Know-Nothing party took over the city and Maryland’s legislature was aghast. Over a century and a half, the city government wrestled back control of the BPD’s budget and appointments, but that quirk in state law, and the perks of state sovereign immunity and non-local ethics laws, still exists.

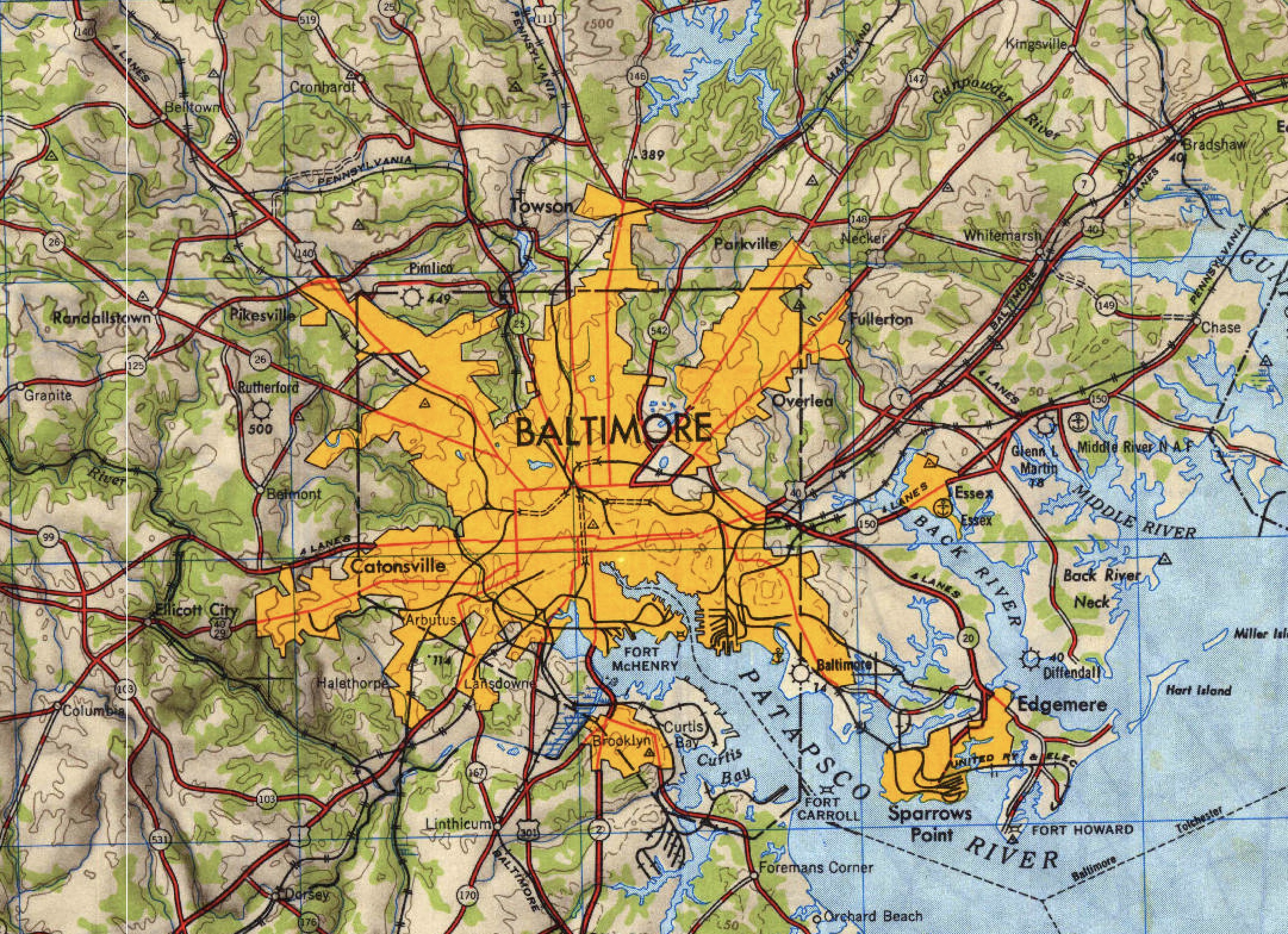

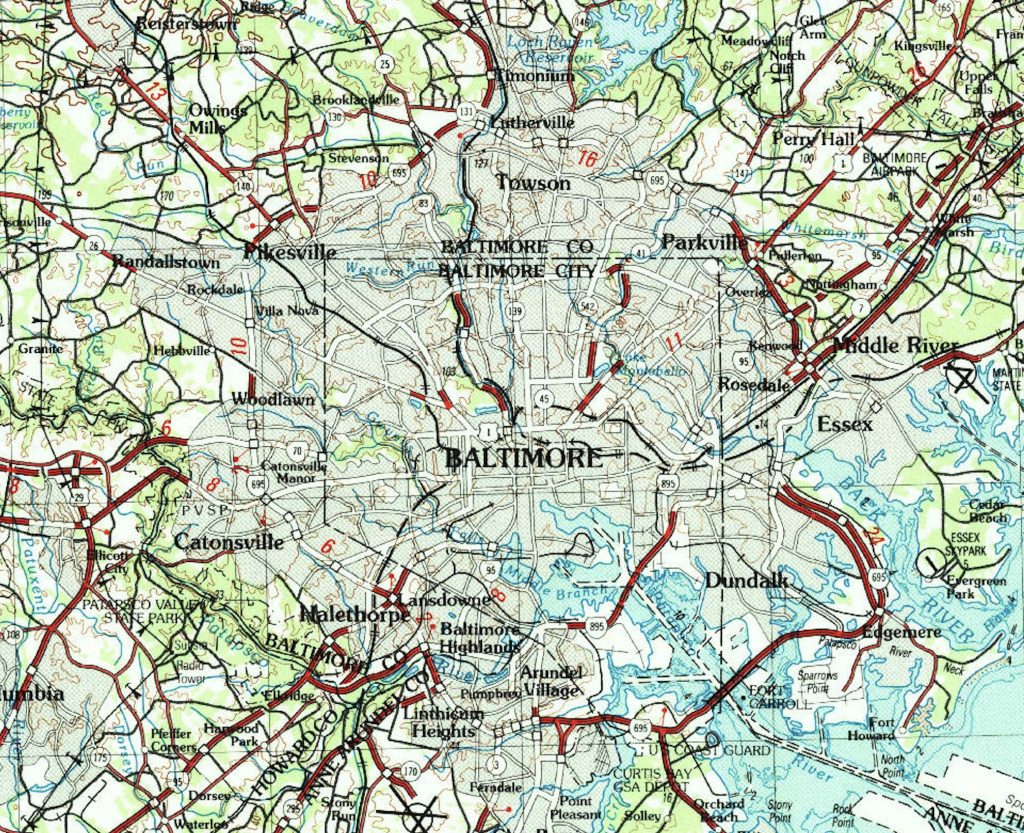

Second, Baltimore City is an 8-mile by 8-mile chunk taken out of the south side of Baltimore County. They are completely separate jurisdictions who only share a name. Different taxes, different schools, different governments. The City has a charter which puts it officially on the same level as any of Maryland’s other 23 counties, but it is the smallest by area, the most developed, the most constrained, and the most over-examined jurisdiction in the state.

The City had annexed land and grew regularly over the first two centuries of its existence. Then in 1948, on a ballot measure put forward by a state senator from Baltimore County, the City sealed its borders. New state annexation rules required a vote of those in the annexation area. At the cusp of interstate highways and booming housing, the City was forever cut off from its growing, wealthy suburbs.

Without that context presented in “We Own This City,” Baltimore City just kind of floats in an ether somewhere around Maryland. The only words from the state level in the show are in the opening credits where Maryland Governor Larry Hogan (R) gets to call the predominantly Democratic City “a poster child for the basic failure to stop lawlessness.”

An unlevel battlefield

Meanwhile, the focus of the show is very much between Baltimore City and the U.S. Department of Justice as federal prosecutors chase down Task Force cops and a federal Consent Decree is negotiated after the killing of Freddie Gray. The show goes to great lengths to express how over policing is deeply tied to the failed War on Drugs. In later episodes, they actually put the words into Brian Grabler’s (Treat Williams) mouth. “Everything changed when they came up with that expression The War on Drugs… With a war comes police militarization, SWAT Teams, tactical squads, Stop and Frisk, strip searches, a complete gutting of the 4th Amendment. It’s like fighting terrorists on foreign soil.”

Foreign soil is an interesting way to put it. The drug war may have been devastating no matter what, but it received an extra receptive audience among counties and cities that are structured to compete with one another. The states set up a system of scarce funds and zero-sum legislative power where there is no incentive for cooperation across municipal lines. For many in the surrounding counties, Baltimore City is foreign soil. The federal war on drugs was fought in states with Balkanized jurisdictions.

The division between Baltimore City and the surrounding counties is only hinted at in “We Own This City.” A shakedown in Carroll County occurs in an obviously large house on a larger lawn. Some detectives from neighboring (and very wealthy) Howard County make side comments about the guys downtown buying their own police equipment. However, there’s little recognition of the political, racial, and cultural effects of crossing an invisible line from one jurisdiction to another.

Those lines create the invisible barrier between the dangerous city and the safe suburbs. They mark a barrier between a city where the residents are 60% Black and homes are worth $150,000, and counties that don’t go under 60% White with homes starting at $250,000. The lines represent breaks between school districts and taxing districts whose fortunes go in opposite directions. They are divisions of responsibility, where once a person escapes across, they’re no longer responsible for those left “inside.”

The result is a functional city fractured into squabbling fiefdoms. Instead of a single city of 3 million people with similar interests, the metro area is spread over six counties each with elected officials who score points by blaming the other jurisdictions. It’s one of the failures of democracy. People excluded from a jurisdiction cannot vote against the fools making terrible policies next door.

Those lines also create self interested lobbying arms at every level of governance. There are 21 police departments in the Baltimore metro area where the total bill runs about $1.25 million per year. Baltimore City Police are only 44% of that budget, and make up less than half of the sworn officers. Only one of those departments has a consent decree, but every one of them has a lobbying day at the Maryland general assembly. Every one of them has political support to request state and federal dollars and the militarized gear that comes with it. Every one of them has the phone number of a sympathetic reporter.

The invisible lines between city and county are the story of the War on Drugs. Without those lines, there wouldn’t have been a field for the War on Drugs to play out across.

“We Own This City” takes a hard look at the scars from the War on Drugs. It witnesses austere City Hall budget meetings and the very personal losses — jobs, children, lives — that disappear while being rounded up on bogus charges. But there’s a broader story that touches into today’s news about why the police aren’t coming and why that’s not a surprise. To understand it fully, it’s vital to see the field of squabbling jurisdictions and hard divisions in self-interest. More importantly, we must recognize that field of broken governance still exists in every American city and is waiting for the next terrible idea to punish another generation.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.