Soon a new change in Washington State law will take effect that could give jurisdictions another set of tools to reduce speeds on their streets and potentially save lives — if local jurisdictions take the state up on using their new authority. The change comes as Washington, along with most of the country, continues to witness the escalation of a traffic safety crisis without one clear cause. However, high rates of vehicle speeds, known to be one of the single biggest factors that determine the severity of injuries sustained from a crash, are not trending in the right direction.

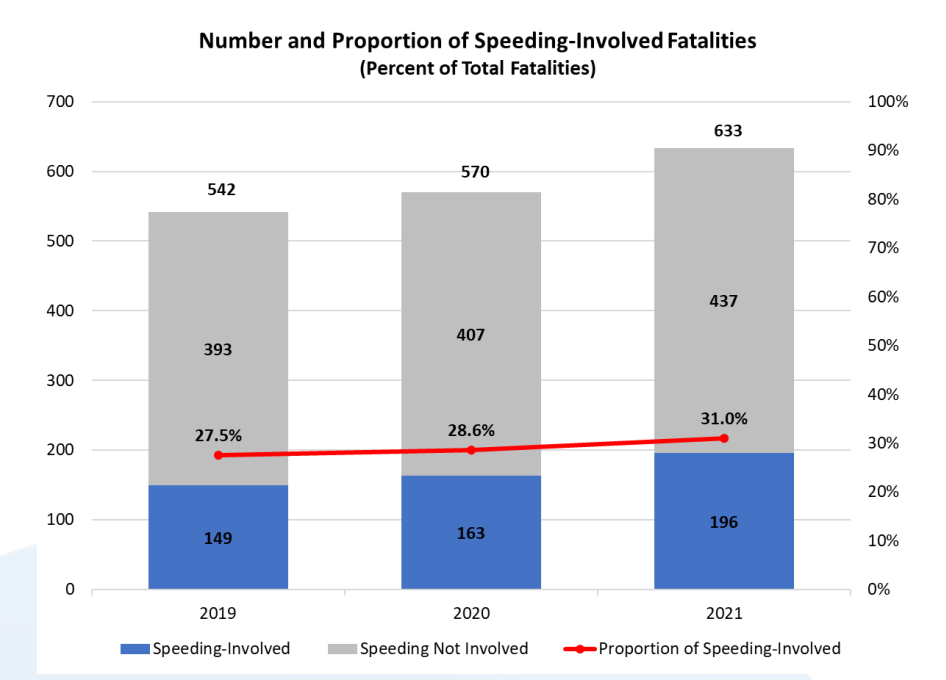

According to the Washington Traffic Safety Commission, in 2021, the state saw a 30% increase from 2019 in the number of traffic fatalities where speeding was determined to be a primary factor in the crash. It’s also important to note that those numbers don’t necessarily reflect all of the streets where the posted speed limit is itself not set at a safe level, which suggests an underreporting of the actual death toll related to unsafe speeds.

Previously, state law dramatically curtailed where cities and towns could add automatic cameras to issue tickets to drivers who exceed posted speed limits. In most cases, the only place where speed cameras could be used was in areas directly adjacent to schools, and the cameras were only able to be in use during the hours immediately surrounding school start and end times. However, when Governor Inslee signed the Move Ahead Washington transportation package this spring, that authority to install speed cameras was dramatically expanded.

More flexibility on installing speed cameras

Starting on July 1 of this year, speed cameras can be installed on any street adjacent to a hospital, park, or along a designated walk-to-school route for any school. For those types of cameras, there isn’t an upper limit on the number of cameras that can be added. In addition, cities can add at least one speed camera, at a location identified as a “priority location” in a road safety plan as submitted to the Washington State Department of Transportation, or at a location where there has been a “significantly higher” rate of collisions than the citywide average over the past three years.

The cameras allowed outside school, hospital, and park zones have to be in locations where localities have determined other traffic calming measures are infeasible or have not been “sufficiently effective.” The number of those cameras allowed is dictated by population, with one additional camera permitted for every 10,000 residents in a city. So, Seattle will be authorized to operate 75 cameras to curtail speeds under that aspect of the law, while Tacoma can operate 23.

The Urbanist contacted the ten largest cities in Washington, where roughly one out of every four Washingtonians live, and asked about any plans to utilize this new authority. So far, no representatives of those cities have confirmed they are moving forward with plans to use the new authority authorized by the Move Ahead Washington package.

Few to no plans for speed camera expansion in cities statewide

While none of the city staff shared plans to expand speed camera as a result of the new authority, some cities already have camera enforcement in place or were already exchanged in expansion before the change in state law was announced.

The City of Kirkland, for example, recently adopted a Vision Zero Action Plan, which spokesperson for the city David Wolbrecht confirmed will include updating and evaluating the city’s policy for setting speed limits. While Wolbrecht said that the city isn’t currently planning any efforts to expand camera enforcement beyond school zones at this time, Kirkland is planning to expand the number of school zone speed cameras by the start of the next school year from three to eight schools, however.

The City of Tacoma is also in the process of adopting a Vision Zero Action Plan. Spokesperson Stacy Ellifritt said that one recommendation currently in that plan is to examine the expansion of automatic camera enforcement.

“It is also worth noting that Tacoma is taking the need to address equity considerations very seriously,” Ellifritt said in an emailed statement. “We plan to be strategic, deliberate, and data-driven when we deploy additional automated enforcement cameras. The Vision Zero Action Plan will include a map that overlays identified safety concerns with Tacoma’s Equity Index. This will be one starting point for potential camera locations. To address equity concerns related to tickets disproportionally impacting low-income individuals, Tacoma currently allows the $124 ticket to be paid in monthly installments of $25 with no additional fees. As Tacoma continues to develop the program, we will learn more if this option addresses equity concerns or if additional work is needed in this area.”

The City of Renton didn’t respond to an inquiry on expanding cameras. That city has a fairly active red light and school zone camera program, with KING 5 reporting in 2019 that one intersection in Renton saw the most red light camera violations in the entire state, with 28,822 citations issued the prior year. While the City of Kent is looking at expanding its use of red light cameras, it hasn’t signaled that it may pursue any different types of traffic camera, and did not respond to questions.

The City of Everett only recently made moves to utilize the authority available under existing law, voting to approve six red light cameras and one school zone camera, nearly 15 years after a council vote to create the program in the first place, but it hasn’t indicated it will be moving to do more in the future.

The City of Spokane confirmed that it’s planning to add three additional school zone speed cameras this year, referencing plans that were already in motion independent of any changes to state law, but it has no immediate plans to add different types of cameras. The neighboring City of Spokane Valley said they aren’t exploring camera enforcement and do not currently utilize them.

The City of Vancouver also did not respond about expanded camera enforcement. Vancouver also doesn’t use any automatic cameras, after a failed attempt to add red light cameras over a decade ago. In 2018, a Vancouver police department spokesperson told The Columbian that “[g]iven our current plan, and our philosophy on community policing, red-light cameras are not something that we believe provides the best option for traffic enforcement,” something that doesn’t bode well for speed cameras either.

Seattle may be an outlier on speed camera enforcement

With so many cities not exactly quick to appear eager to use this new authority, it increasingly looks like Seattle may be the first city to take advantage of the change in state law.

“We are aware of the expanded authority to place speed cameras in additional locations around the city,” said Mariam Ali, spokesperson for Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), in a written response. “We will be working sometime in the near future on exploring the potential locations of where we would like to place these additional speed cameras. Once we have those conversations and determine where we will like to place those additional speed cameras, we will let the public know.”

Seattle is currently conducting a pilot program on transit lane and intersection blocking cameras, which is currently set to expire in 2025, and it is also adding new school zone speed cameras this year. Furthermore, several elected officials have specifically called for new speed cameras to improve safety.

After the Seattle City Council held a discussion on traffic safety in its transportation committee this week, committee chair Alex Pedersen (District 4) came out in support of adding more speed cameras. “While we have lowered speed limits, expanded access to mass transit, and increased crosswalks, we must also respond to the drop in police enforcement by increasing use of speed cameras and fines based on ability to pay,” Pedersen wrote in a press release.

Seattle Councilmember Tammy Morales (District 2), who has been the most outspoken councilmember on the issue of traffic safety in recent months, was less prescriptive, but also raised the possibility of installing more speed cameras. Morales’s district in the southeast quadrant of the city has seen an incredibly oversized share of traffic fatalities: in 2021 over half of the traffic deaths on the streets occurred there.

“I know you are working with community members who want to focus on non-punitive measures,” Morales said to SDOT staff during the committee meeting. “But I will also tell you that those students at Rainier Beach High School, that’s the first thing they said: ‘Double the fine, put more traffic cameras in,’ because they’re fearful of being hit by a car trying to get to school.”

Cities can set their own rates for speeding fines, but under state law half of all revenues generated after overhead by the new camera authorizations have to be deposited in the state’s Cooper Jones Active Transportation Safety account. It’s the Washington Traffic Safety Commission that will determine how to spend those funds, and it’s been doing the same for the Seattle-specific camera pilot.

Since that agency generally can’t directly fund physical infrastructure, so far it has signaled interest in providing resources that allow cities and towns to apply for grants that would fund infrastructure improvements. However, it’s not clear what would get funded if the amount generated by these cameras were to dramatically increase with cities across the state using the new authority.

So far, though, that doesn’t look to be a concern any time soon. While permitting cities to expand speed cameras was one of the biggest changes related to traffic safety undertaken by the Washington State Legislature in 2022, it’s clearly going to take a little more of a nudge to get most cities around the state to actually take advantage of that authority. In the meantime, traffic deaths and serious injuries continue to climb.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.