Today the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) unveiled its rezoning concepts for the 2024 Comprehensive Plan Update, which will guide growth for decades to come. OPCD’s thinking revolves around four broad concepts, plus a “no action” alternative, which Washington State mandates as a study baseline.

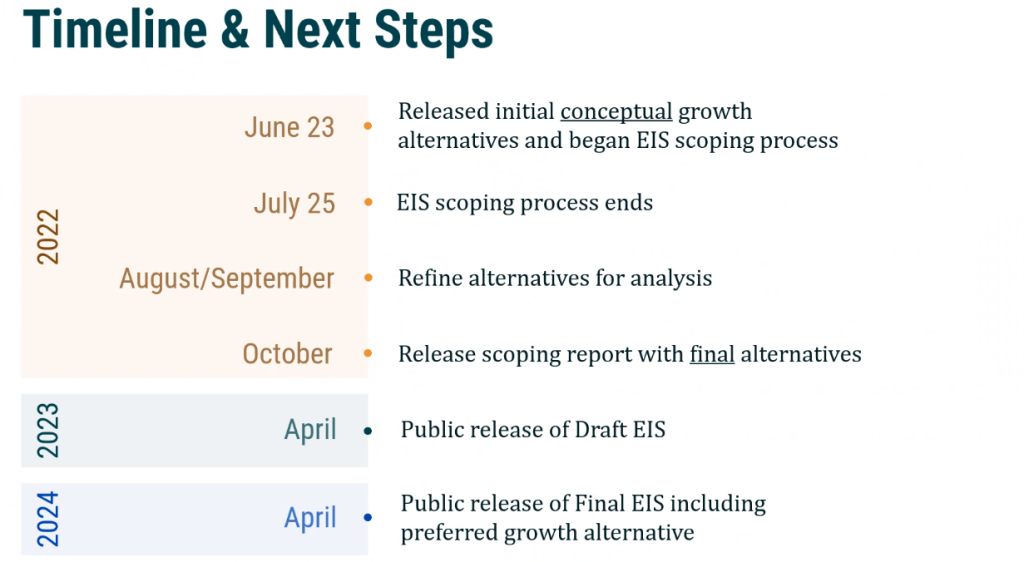

The agency has opened a public comment period that runs through July 25 and is welcoming feedback on the concepts, which are very high level at this point, at its public engagement hub. The public feedback during the scoping phase will inform the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), which is due in April 2023 in OPCD’s timeline. The Final EIS will then be released in April 2024 and voted on by the end of 2024, leading to zoning changes by 2025, as well as the accompanying tweaks to other official city plans, such as the Seattle Transportation Plan.

“We need your input to ensure we are considering the right range of options for where we encourage new housing and jobs in Seattle,” said Rico Quirindongo, acting director of OPCD, in a statement. “Rental housing costs remain a severe burden for thousands of residents and the lack of homeownership opportunities are forcing many people to look outside the city when purchasing a home. We must also reduce displacement pressures on Black, Indigenous, and other people of color who have borne too many of the negative impacts of population and economic growth.”

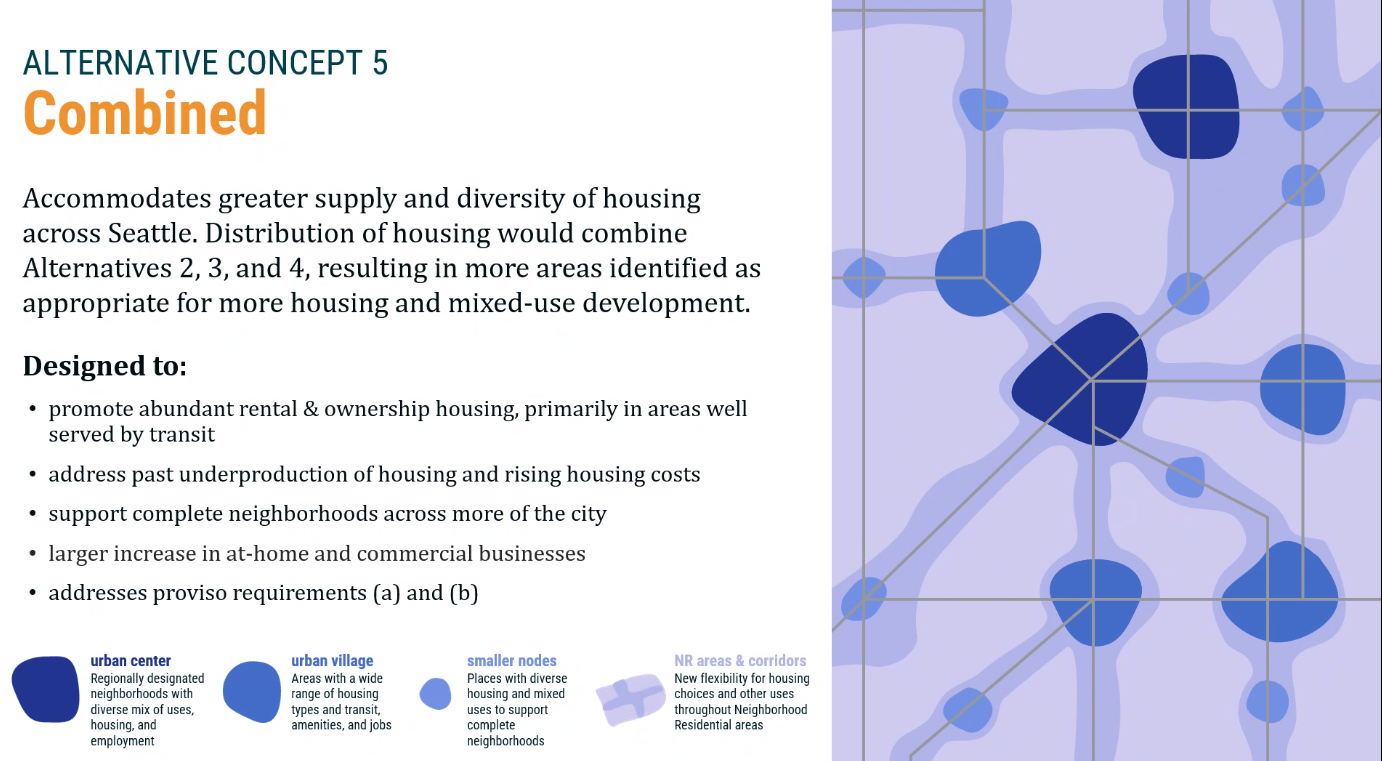

For urbanists, the “Combined” Alternative 5 emerges as a clear favorite as it combines a “missing middle” gentle density approach in Neighborhood Residential zones with more focused zoning changes on transit corridors and in expanded urban village boundaries, allowing for the best of both worlds. Alternative 5 would best encourage housing growth, promote a diversity of housing choices, while also pulling in more affordable housing contributions via the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, which does not currently apply to development in Neighborhood Residential zones, which is predominantly single-family detached homes.

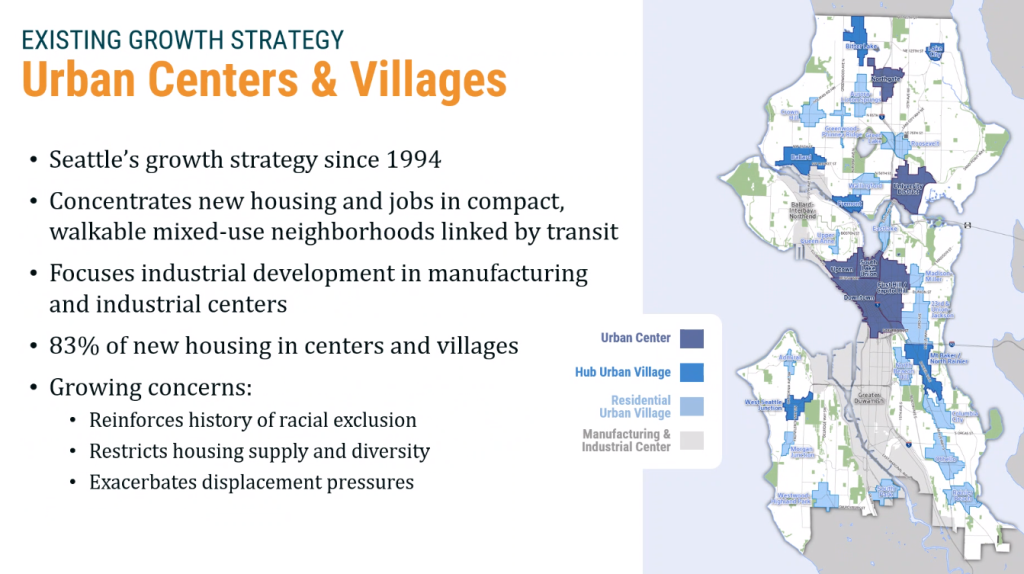

Of the alternatives, 5 would be most effective in getting Seattle out of the rut it’s been in following implementation of the “Urban Village Strategy” in 1994, a strategy which has been changed only nominally since and has contributed to mounting displacement pressure and skyrocketing housing costs. The strategy has led to 83% of new housing growth occurring in these urban centers and urban villages which compose about 10 square miles of a 84-square-mile city. Neighborhood Residential (or single-family) zoning composes about 30 square miles, in comparison, and some single-family neighborhoods have actually shrunk in population, even as the city grew rapidly as a whole.

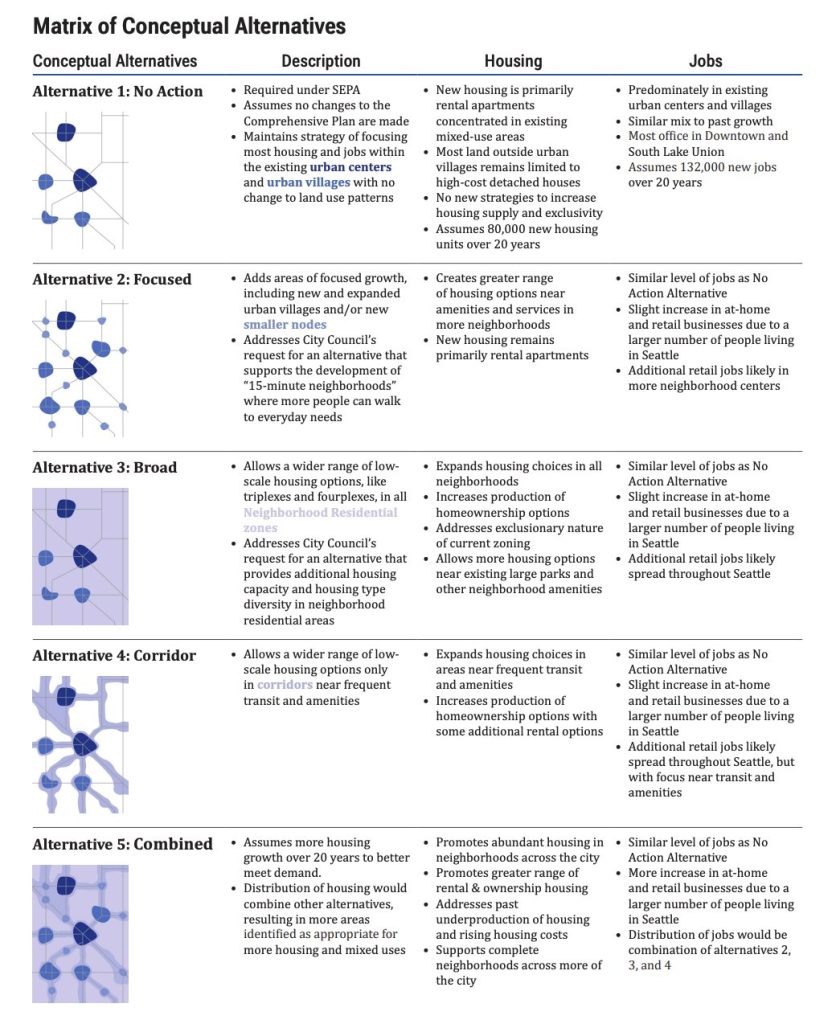

Here’s how OPCD laid out the five conceptual alternatives being studied:

- Alternative 1: No Action – “Maintains strategy of focusing most housing and jobs within the existing urban centers and urban villages with no change to land use patterns,” OPCD notes. “Most land outside urban villages remains limited to high-cost detached houses. Assumes 80,000 new housing units over 20 years.”

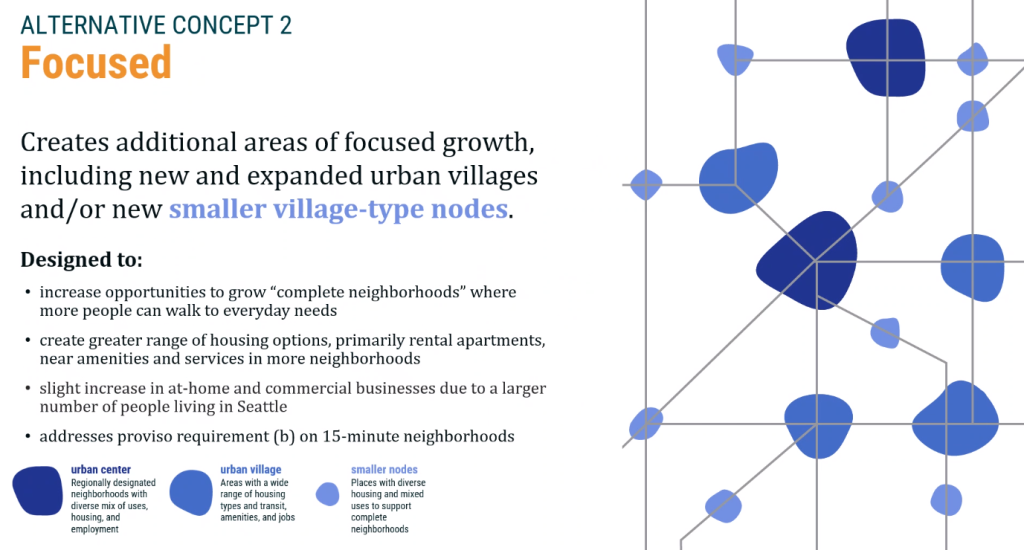

- Alternative 2: Focused – “Adds areas of focused growth, including new and expanded urban villages and/or new smaller nodes,” OPCD writes. “Most land outside urban villages remains limited to high-cost detached houses.”

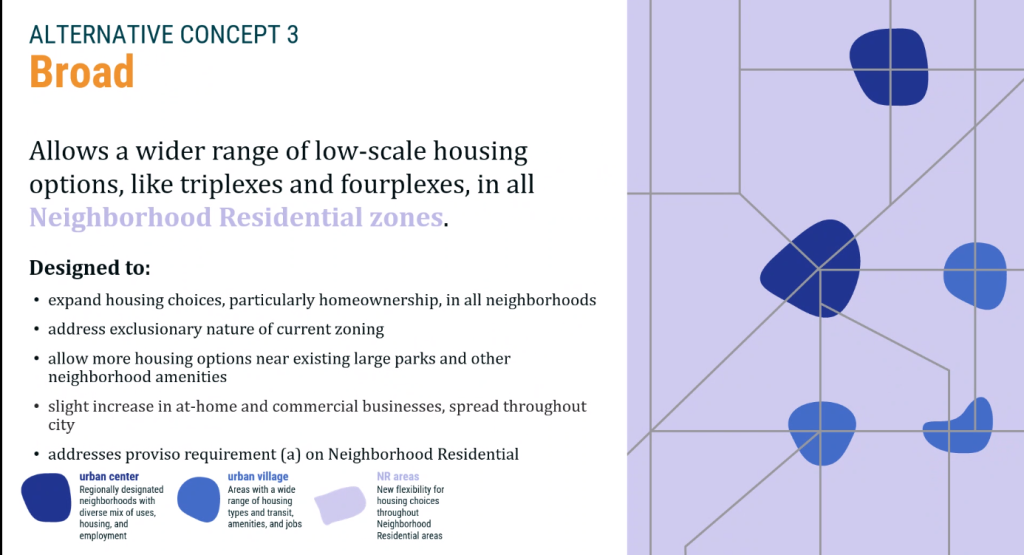

- Alternative 3: Broad – “Allows a wider range of lowscale housing options, like triplexes and fourplexes, in all Neighborhood Residential zones,” OPCD writes. “Expands housing choices in all neighborhoods… Allows more housing options near existing large parks and other neighborhood amenities.”

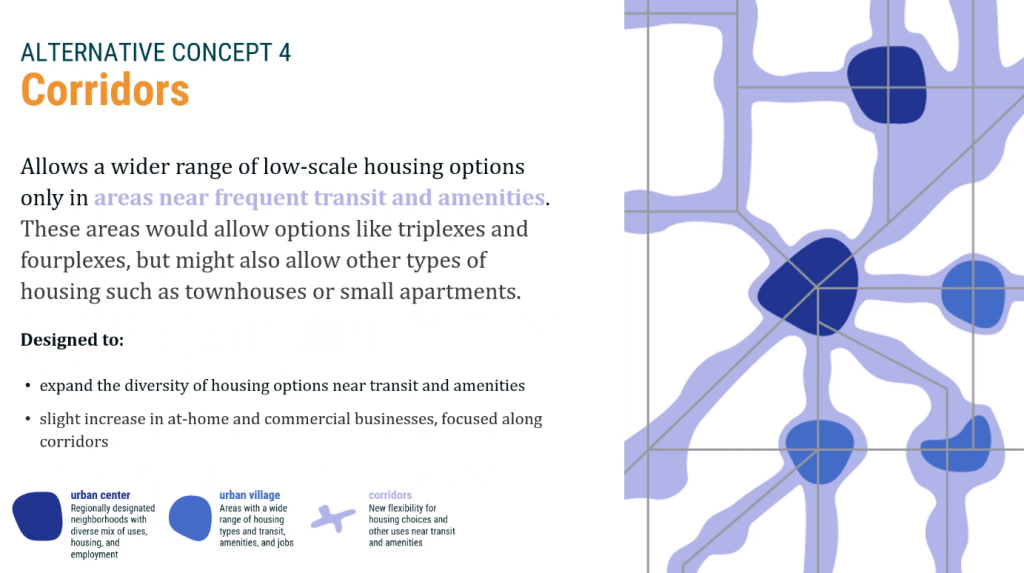

- Alternative 4: Corridor – “Allows a wider range of lowscale housing options only in corridors near frequent transit and amenities,” OPCD writes. In 2019, the City calculated that 70% of Seattle’s population lived within a 10-minute walk of frequent transit thanks to Seattle Transportation Benefit District bus investments, which Seattle voters renewed in a landslide in 2020, albeit at a diminished size.

- Alternative 5: Combined – “Distribution of housing would combine other alternatives, resulting in more areas identified as appropriate for more housing and mixed uses,” OPCD writes. “Promotes abundant housing in neighborhoods across the city. Promotes greater range of rental and ownership housing. Addresses past underproduction of housing and rising housing costs. Supports complete neighborhoods across more of the city.”

Alternative 2 would appear to implement the Seattle Planning Commission’s “hamlet” strategy adding small nodes between the city’s 30 designated Urban Villages and Urban Centers. Both the Planning Commission and City Council leaders such as Teresa Mosqueda and land use chair Dan Strauss have also backed expanding missing middle housing options broadly in Neighborhood Residential zones, formerly known as single-family. That policy preference is encapsulated in Alternative 3.

Mayor Bruce Harrell, meanwhile, has indicated a preference for zoning changes near transit corridors while opposing blanket changes to Neighborhood Residential zones. Alternative 4, then, seems to align with that position, but some urbanists have criticized the impulse to funnel nearly all apartment growth near busy, loud, polluted, crash-prone streets where frequent buses run — think the RapidRide E Line on Aurora Avenue, which is among the deadliest roads in the state, or Route 7 on heavily crash-prone Rainier Avenue.

Alternative 5, if done well, appears to have the possibility of taking the best from all three of those growth strategies. However, at this scoping stage it’s important to give feedback at how best to scope each alternative so the menu of options is all better. Potential feedback ideas to sharpen the concepts as they advance to fleshed-out alternatives include:

- Alternative 2 should study adding highrise and midrise zoning. Currently, OPCD appears mainly to be thinking about adding lowrise and perhaps some new areas zoned for six-story buildings, such as the nodes in Alternative 2 and 5. Denser zoning types would generate more MHA contributions that expand the city’s affordable housing stock. Zoning from midrise to 18-stories appears ideal for mass timber construction, which could greatly reduce the carbon cost of buildings while providing high quality homes. The burst of highrise development in the University District shows that Seattle can likely attract tower development in additional high demand areas, such as Ballard, Uptown, Mount Baker, and so forth.

- Alternative 3 should study a wider range of missing middle housing types rather than just triplexes and fourplexes. The state legislature contemplated requiring sixplex zoning near frequent transit. This should be the bare minimum to study so as to not restrict policymakers with a lesser option. Rowhouses, stacked flats, or courtyard apartments would also fit in well in Neighborhood Residential zones.

- Alternative 4 should study significant upzones in a broad area around transit corridors, not just a narrow band near the arterial street. A 15-minute walkshed would make sense given Seattle’s 15-minute city aspirations, but the transportation plan must improve walkability and safety in these busy corridors for the plan to really thrive. When it comes to EIS work, it’s easier to subtract than to add once scoping parameters have been set.

- Alternative 5 should seek to quantify the impact to the housing affordability crisis that the extra housing and MHA contributions would have. Many cities do the bare minimum when it comes to comprehensive planning under the Growth Management Act. What would happen if a city embraced growth and more affordable and attainable housing types like missing middle and apartments? Could displacement be curtailed? It would be nice to find out.

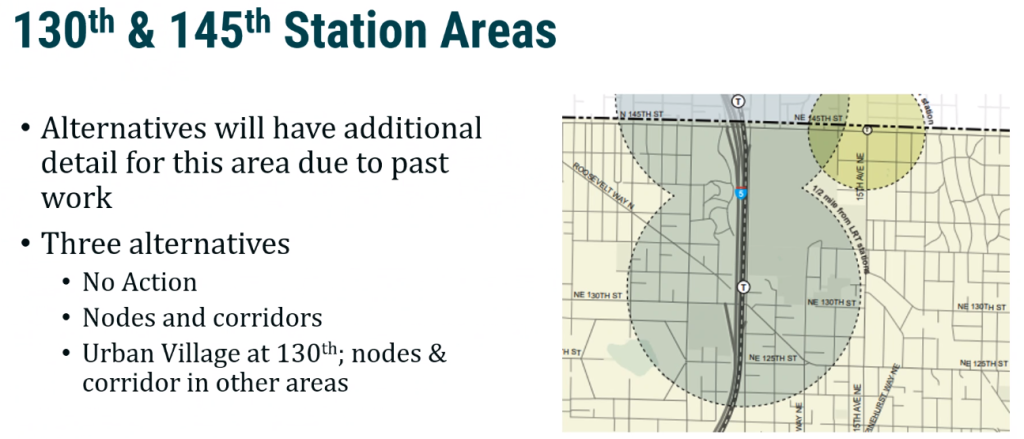

- Maximize housing opportunities near planned light rail stations. By 2026, 130th Street Station is expected to open in North Seattle. The City should establish an urban village around the station rather than squandering this huge investment and major opportunity to establish a 15-minute neighborhood. Likewise Avalon and Junction could use expanded urban villages since they’re expected to get light rail in 2032, as could Ballard, Interbay, and Uptown — expecting light rail in the mid 2030s.

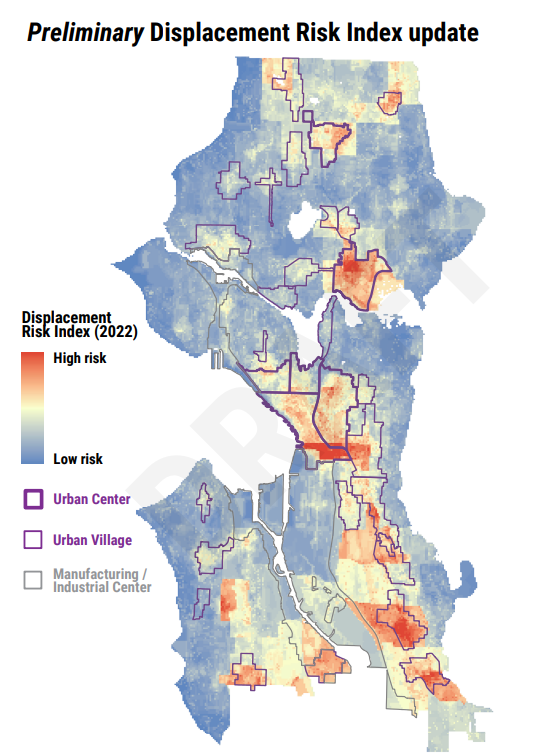

OPCD said overall it is aiming to focus housing growth where displacement risk is low and opportunity is high, but it doesn’t want to freeze areas where displacement risk is high in amber, either, and will look to expand housing choices there in a more measured way. Areas with high displacement risk do tend toward the South Side, but not exclusively. North Seattle neighborhoods like the University District, Northgate, Lake City, and Bitter Lake also show up in OPCD’s updated displacement risk index, along with places like the Rainier Valley, South Park, Westwood-Highland Park, White Center, and the Central District.

In its materials, OPCD noted the parameters under which it is conducting work on the Comprehensive Plan update. Some of those come from direction from the Seattle City Council, who view the update as an opportunity to study the following growth strategies:

- Allowing new types of housing in Neighborhood Residential areas citywide;

- Supporting development of “15-minute” neighborhoods where people can walk or bike to everyday needs; and

- Using other strategies to address displacement.

In addition to these goals, the City is trying to achieve other city and regional goals, with OPCD listing the following:

- Meeting regional requirements to plan for at least 170,000 jobs and 220,000 additional residents for the 2019-2044 time period;

- Increasing housing supply, diversity, and affordability;

- Addressing past and ongoing harms from housing discrimination and exclusionary zoning;

- Leveraging investments in transit, especially new light rail stations;

- Mitigating and addressing the impacts of climate change; and

- Aligning investments with the expected growth pattern.

Seattle’s last major Comprehensive Plan update in 2015 aimed to accommodate 120,000 new residents over 20 years. In 2015, The Urbanist editorial board pushed the city to go bigger by expanding and adding more urban villages, but the City stuck with the more modest changes it had planned. Seattle ended up adding about 130,000 residents between 2010 and 2020 alone, according to census figures, which suggests the previous growth target was set too low. Seattle’s median single-family home prices jumped from $535,000 in March 2015 to exceeding $1 million in 2022. Price jumps on the Eastside have been even steeper, and South King and Snohomish County suburbs are rapidly catching up, too.

Targeting 220,000 residents over a 25-year period is a little better, but still could be aiming too low, particularly if avoiding the jobs-housing mismatch that is driving the region’s runaway housing price growth is a goal — and it should be.

If you’re wondering what the heck an EIS even is and why you should care, Ray Dubicki has a great explainer and OPCD has done a short video laying out the basics:

Today’s reveal of the proposed alternatives makes it feel like this marathon toward a new growth strategy for Seattle has finally kicked off in earnest. The sooner Seattle can produce more homes for everyone — and especially for residents being pushed out or denied access to the city due to the lack of affordable options and family-sized housing — the better.

Submit public comment: Once again, the deadline for public comments on what to study in the environmental review is July 25. More information about the process and how to comment is available on the OPCD Public Engagement Hub.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.