Few things perfectly encapsulate the problems of planning like a city’s land use code. Unlike the building code, which dictates the life safety requirements to make sure a building doesn’t burn down or collapse, the land use code simply sets your building’s height, location, and how much of it can be built.

100 years ago, the land use code was as thick as a children’s book. It was simple enough that out-of-town developers like John Wallingford, L.H. Griffith & E. Blewitt, James Moore, and many others moved to the city to build anything from kit craftsmen bungalows to mid-rise apartments without thick packets seeking the city’s approval. This allowed for speedy housing delivery to match the city’s robust job and population growth.

But today, Seattle’s official land use code is 1,400 pages long. To read it cover to cover is the same as reading the Holy Bible from Genesis to Revelations, while tacking on another 200 pages just to call it even. Charles Darwin explained how all life on Earth came to be in just 502 pages, yet we can’t even describe a desired building in Seattle’s land use code with a book three times as thick. It has become a lesson in urban micromanagement, a lesson that ends with housing shortages, soaring costs, segregation, and unequal development practices that often pick on the poor and disadvantaged.

Seattle’s land use code makes ugly buildings

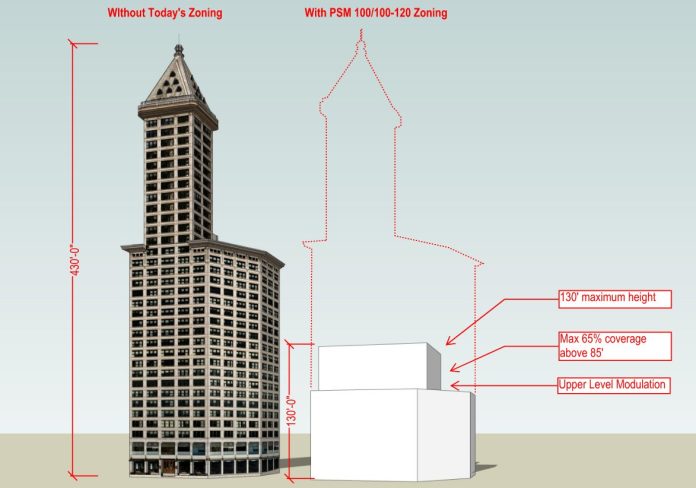

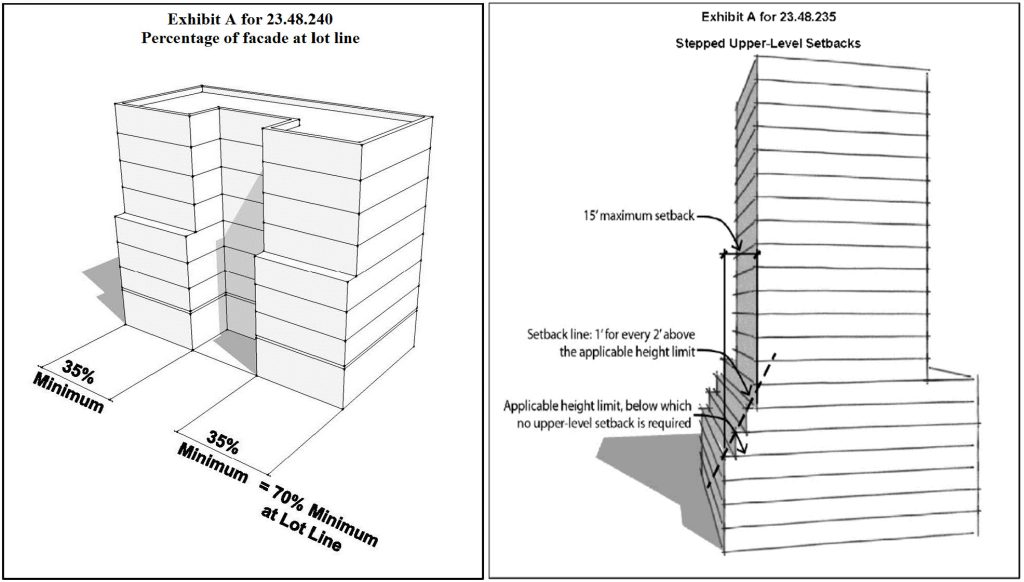

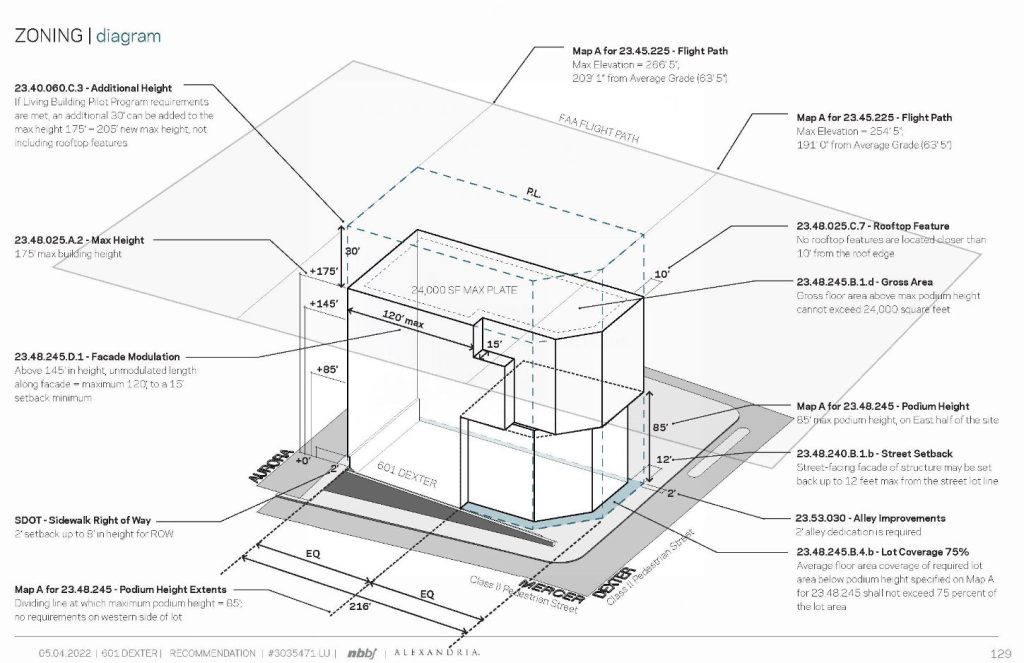

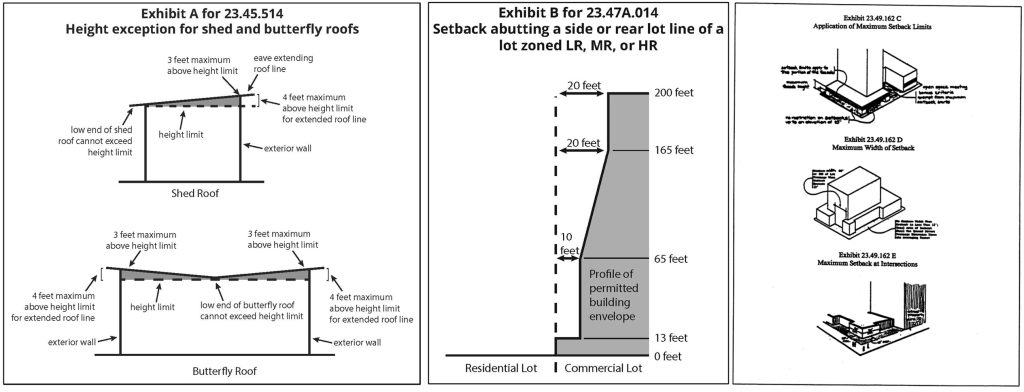

Design is subjective and, in my estimation, pointless to argue about in a housing crisis, but for those architectural critics out there, the land use code is what makes buildings look weird and wonky. Too many requirements for setbacks, modulations, and floor area limitations dictate what all our structures look like.

The zoning code is so micromanaged it blankets every lot like a straight jacket outlining what a building can be. In the thousands of pages and years of revisions, planners have calculated how much area matches the height of a zone and then added ticky-tacky setbacks and modulation requirements to get developers to “commit” to more expensive buildings. A commitment that trickles down to higher rents and home prices.

If this is what we want our buildings to look like, then great, the planners have mastered it. But something tells me this is a bluff. Planners set the stage for the wonkiest shape possible and force applicants to ask for code changes. This comes with an adversarial tone from the city’s Design Review Boards, who ask for development tradeoffs or are skeptical of the request which just puts all our vital multifamily housing and the Mandatory Housing Affordability funding contributions they come with on trial.

Streamlining for sustainability

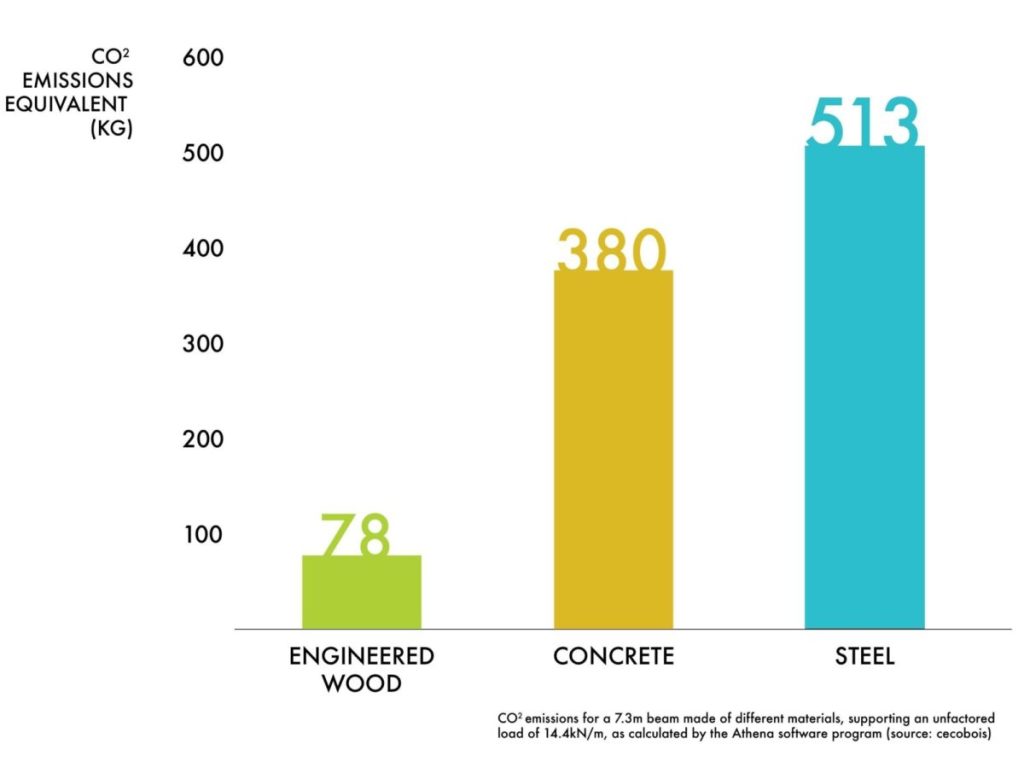

Seattle’s desire for carbon neutrality and sustainability is well documented. Seattle City Light offers 100% clean energy, and with the city mandating bicycle commuter facilities, switching to electric vehicles, and expanding the robust energy code to reduce the impact on new construction, this shows Seattle’s commitment to sustainability. Architects have been pushing for mass timber construction to replace the embodied carbon that comes from building with concrete and steel.

It’s a no brainer since wood sequesters carbon and concrete or steel exhaust it in production. But wood buildings have limitations and Seattle’s land use code makes it next to impossible to choose anything over concrete or steel. Developments seeking timber die on the drawing boards because of Seattle’s land use restrictions.

Timber buildings prefer to be simple and beautiful. With wonky setbacks, modulations, and floor area limitations, a simple box is not possible to build. Every step is another column and another reason to switch to concrete. If the city is serious about its goals, it’s time to get real on what that land use code is doing to add embodied carbon emissions every time something is built.

Passive House construction is a method of building that reduces energy use and makes buildings healthier and occupants happier. But like timber, passive house construction prefers simplicity. The fewer ins and outs, the better. Every step back is another surface, another chance for air or heat leakage. Like timber, many goals for passive house construction die during feasibility or design when the land use code just makes it next to impossible to achieve.

What kind of city makes you commit to embodied carbon? To do away with this we must rethink the whole code from the lens of sustainability. Eleven years ago Brussels updated their code so that all new buildings met passive house standards.

Speeding up housing

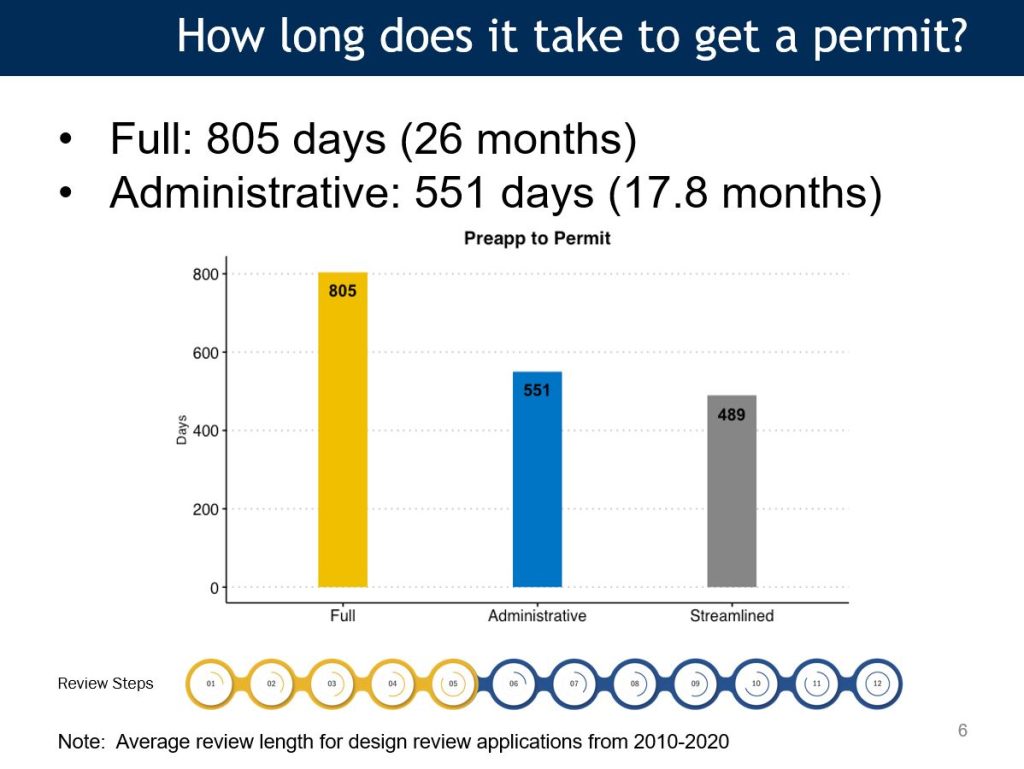

Another problem with thickening the land use code into an encyclopedia is long review cycles. Even the simplest building proposals seeking no variances must document their compliance in a thick set of plans before they can pursue a construction permit. Planning departments are stacked to the brim with mountains of other problems ranging from displacement protections, zoning changes, transportation plans, and other building permit applications.

Spending time reviewing a building from the lens of self-imposed land use micromanagement seems like a misallocation of time. And, since every building is now an affordable housing project through the city’s Mandatory Housing Affordability program, we don’t have time to waste. Holding up homes and millions of dollars to build affordable homes seems like a step backwards for what this city needs and what City Hall is striving for.

Oh, did I mention that timber buildings also go up faster than concrete and steel ones?

The new code we need

The solutions we need today are more in line with the solutions we had in the past. From the day the Empire State Building’s land was acquired until the doors first opened only took 600 days. This included fifteen redesigns, permitting and construction timelines. Today, it takes over 800 days in Seattle just to get to construction and have shovels hit the ground. 500 days of that is stuck in land use review. This should not come as a surprise considering there are hundreds of pages to thumb through just to make sure a building complies. This problem is self-inflicted.

The city’s planning department should be taking hundreds of pages out of the land use code every year. Start with the lowest hanging fruit, things like parking requirements, loading berths, and other wonky silliness. Then move to bigger things like setbacks, modulations, transparency requirements, and streamline the whole thing down.

We want beautiful buildings, right? Then legalize them again. Eliminate all the silly nonsense about setbacks, modulations, ground floor standards, and upper floor limits. Then just define what a building height shall be and how much area you can build. Simple boxes are beautiful once they’re detailed and articulated. It also turns out they’re the best thing for sustainability too. Let’s encourage the buildings that deliver homes and sustainability. Let’s cut the red tape of process and become a more equitable, sustainable and beautiful city. We don’t need public input veto points (processes which are dominated by White homeowners) for every little thing. We need cities that meet our environmental and housing goals and that don’t trip ourselves up in the process.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.