Ridehailing appears to be on shakier foundation than transit coming out of the pandemic.

As commuting patterns slowly return to normal, ridehailing appears to have continued its pattern of swiping riders from transit in many parts of the country. However, in the Seattle region, ridehailing has been slow to recover and is rebounding even slower than transit, based on a recent glimpse into the data in the Seattle Times.

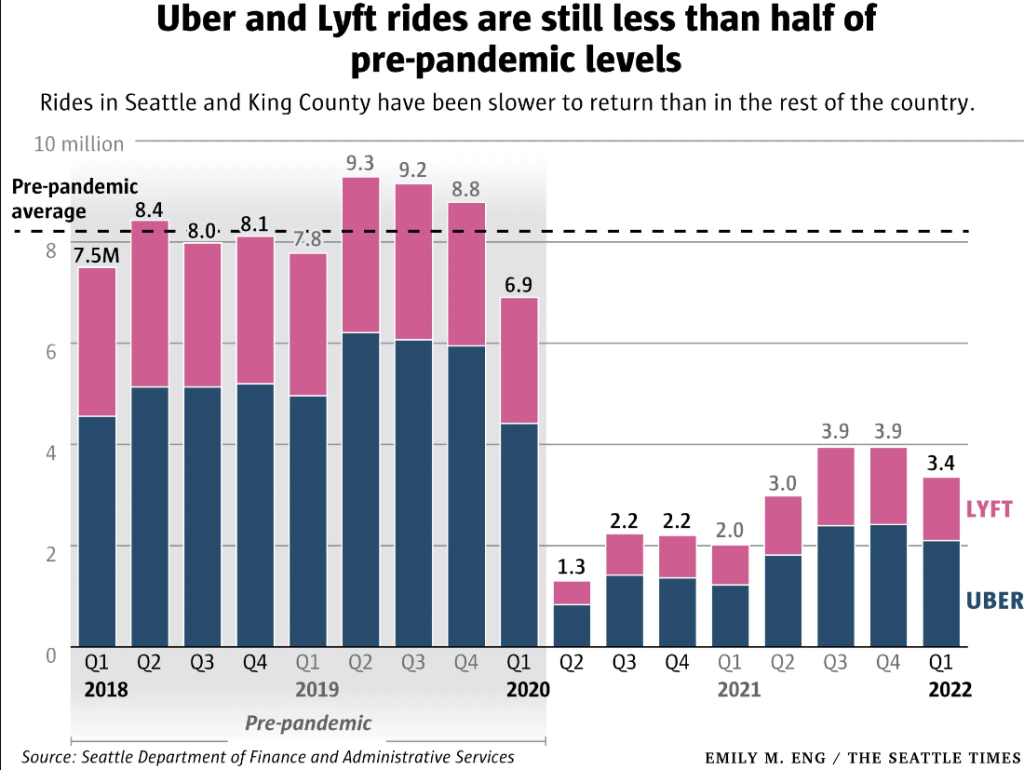

“In the first quarter of 2022, drivers for Uber and Lyft provided around 3.3 million rides in King County, according to data provided by the Seattle Department of Finance and Administrative Services through a public records request. That’s just 36% of the companies’ combined 2019 peak of 9.3 million rides,” David Kroman wrote. The companies claim to be at about 70% of normal ridership in most other metropolitan regions.

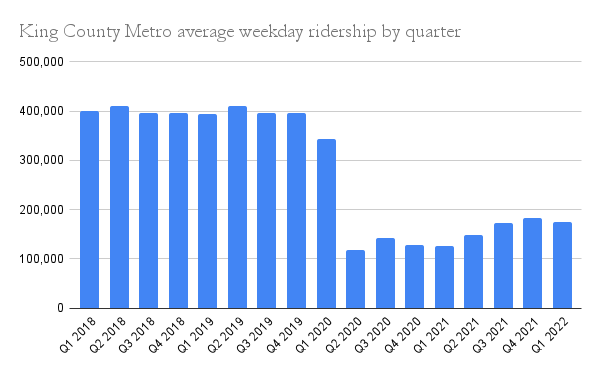

That quarterly figure converts to about 36,000 ridehailing fares per day. By comparison, King County Metro reports its bus ridership has continued to rebound from its pandemic doldrums and hit a new pandemic-era high of 217,000 boardings on June 1st. In 2019, Metro hovered around 400,000 average weekday boardings. In April, Metro ridership clocked in at 49% of its 2019 level.

Uber and Lyft struggle to retain drivers or turn a profit

For their lagging numbers in the region, Uber and Lyft have sought to blame Seattle’s 2020 law applying a minimum wage equivalent of about $16 to ridehailing drivers, whom the industry has fought hard to keep classified as independent contractors rather than employees. But blaming the minimum wage law doesn’t pass the sniff test. After all, the companies are reporting a shortage of drivers, which suggests their wages, if anything, are still too low. In fact, the ridehailing workforce has been trending down since 2018, and the higher compensation mandated by the City of Seattle likely helped them retain more drivers than they would have otherwise.

“Many drivers in King County and elsewhere in Washington appear to have stopped working for Uber and Lyft altogether, a nationwide issue for the companies that threatens to fray their coverage,” Kroman wrote. “In 2021, King County issued 12,285 ride-hailing permits to drivers, according to the King County Records and Licensing Services Division. In 2019, that number was roughly 80,000; in 2018, it was nearly 90,000.”

The difficulty in retaining drivers is also linked to fewer fares to go around, making work more sporadic for drivers. Lucrative fares being fewer and farther between means drivers have to work longer periods to make the same amount of money as previously when fares stacked up one after the other, with less extra driving or waiting searching for fares. With unemployment extremely low in King County, many drivers have left the sector for other occupations given the host of job opportunities.

Uber and Lyft have jacked up prices significantly, but most of that is not being passed along to drivers. Instead, the companies are keeping more for themselves in an increasingly desperate attempt to finally turn a profit after a decade of loss-leading growth with little abandon. Those higher prices should also be among the first culprits we look to explain lower demand, rather than blaming drivers for not working for peanuts. It’s also possible people have simply fallen out of the habit of using these services during the pandemic.

Slate‘s Henry Grabar noted Uber’s average prices have nearly doubled over the last four years according to some estimates and still profits have been elusive. The lack of profits and increasing pressure from investors led Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi to issue an ultimatum to employees warning their “bull run” was over and a new approach was needed, alluding to belt-tightening austerity on the horizon.

“Average Uber prices rose 92 percent between 2018 and 2021, according to data from Rakuten; a separate analysis reports an increase of 45 percent between 2019 and 2022,” Grabar wrote. “Both Uber and Lyft have added a surcharge for riders that helps drivers account for high gas prices. And all that was before last week’s ultimatum.”

As we’ve pointed out before at The Urbanist, the ridehailing business model appears flawed on a fundamental level for a number of reasons. Operating a car is really costly — even offloading a great deal of the costs on the privately contracted driver and society writ large. A spike in gas prices eats into a driver’s profit margin, as does rising vehicle costs. Uber has always assumed increasing scale would lead to profits, but it just hasn’t happened even as the company has grown enormous, driven most traditional taxi companies out of business, joined the Fortune 500, and achieved a $42.8 billion market capitalization.

Uber and Lyft have struggled even with U.S. authorities taking a largely hands off approach to regulating them, let alone taxing them on par with the traditional taxi services that proceeded them. Some jurisdictions have even promoted ridehailing companies in place of their own transit services. Venture capital and other investors continued flushing billions of dollars into ridehailing companies over the past decade despite the lack of profits and diminishing light at the end of tunnel.

Earlier hopes that autonomous robot cars would suddenly turn the business into a profitable one have been dashed as the much-ballyhooed technology has been slow to materialize. In 2020, Uber sold off its self-driving research venture, which they had sunk $1 billion into, and Uber’s head of self-driving was sentenced to 18 months in prison after pleading guilty in 2019 to stealing trade secrets from competitor Waymo. Even with those secrets and considerable investment, Uber didn’t appear particularly close to rolling out self-driving cars at scale. Operating in dense urban environments could be one of the technology’s biggest hurdles to overcome since self-driving cars continue to struggle to detect pedestrians. Dense urban environments is where Uber and Lyft do much of their business.

Telecommuting upending travel patterns

Much of Seattle’s tech and white collar workforce continues to enjoy the option to telecommute, which had been implemented as an emergency measure to combat spread of the coronavirus but has proven popular with many workers. While some employers have tried to get workers back into the office, many have implemented hybrid work arrangements, which means a good chunk of workers are only in the office a day or two per week. The upshot of this is travel demand to Downtown Seattle is much lower than it was pre-pandemic even though 323,000 jobs are based there — at least on paper, according to figures from the Downtown Seattle Association.

Some policymakers and pundits have been worried the pandemic has taken a permanent bite out of transit demand and suggested ridership will never return to 2019 highs. That seems a premature conclusion to make, but certainly the transit industry must grapple with a lower ridership reality for the time being.

One positive that could come out of ridehailing’s slow rebound in Seattle is transit getting a bigger chance to win those riders back. The data shows the ridehailing clearly competes with transit, with the busiest ridehailing markets overlapping with major transit routes. Traditionally, ridehailing used aggressive below-cost pricing to lure customers, but this time around the ridehailing giants cannot afford the same level of rider subsidy.

“One well-known consequence of the rider subsidy is the decline in public transit,” Slate‘s Henry Grabar wrote. “One study estimates the arrival of Uber and Lyft in a city decreases rail ridership by 1.29 percent and bus ridership by 1.7 percent each year. In San Francisco, where Uber was founded, the authors estimate Uber has decreased bus ridership by 12.7 percent. A second study concluded a 5.4 percent decline in bus ridership in midsize cities. A third study clocked the decline at 8.9 percent. A related Uber phenomenon has been a sizable increase in downtown traffic congestion.”

Overall, regional car traffic volumes are at about 95% of pre-pandemic levels, Kroman reported, and traffic congestion is starting to roar back. The increase in telecommuting has smoothed some of the edges from peak congestion periods, but overall traffic is nearing pre-pandemic levels. That has meant some familiar delays for bus riders after a brief pandemic reprieve from traffic snarls.

Returning to normalcy is top of mind at this stage in the pandemic, but normalcy could use some improving upon. Things like faster and more reliable transit come to mind. More dedicated bus lanes and signal priority to get buses through clogged intersections could help achieve it, but the pandemic has also slowed down roll out of RapidRide upgrades to Metro’s bus network — not to mention set back Sound Transit’s light rail and bus rapid transit expansions by a few years. Local leaders should act swiftly to speed up transit upgrades and get projects back on course.

While transit should be the focus for policymakers, ridehailing has an important role to play despite its foibles — particularly if cities are to be successful in creating more car-lite neighborhoods and decreasing dependence on parking. Grabar pointed to ridehailing’s positives in his piece.

“While the transportation-network companies probably increased vehicle ownership, they also gave cities cover to reduce expensive parking mandates, and developers responded with smaller garages or no parking at all,” Grabar noted. “The builders of Cul de Sac, Phoenix’s first parking-free development, credit the rise of ‘ride sharing’ for making their project possible. It has also changed the model for restaurants and bars, which don’t require as much parking as they used to. That’s good for land use and very good for drunken driving rates, which have fallen significantly as Uber uptake has increased.”

It appears ridehailing makes more sense as an occasional luxury rather than an everyday workhorse service competing with transit for daily commuters, given its rapidly rising cost and the congestion impacts it brings. Seattle and Tacoma were leading the nation in forming car-free households prior to the pandemic. A level of ridehailing service that supports that pattern would be a welcome benefit to cities. However, whether ridehailing giants will settle into a symbiotic relationship with cities or thrash about looking for total domination of markets and disruption for disruption’s sake remains an open question.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.