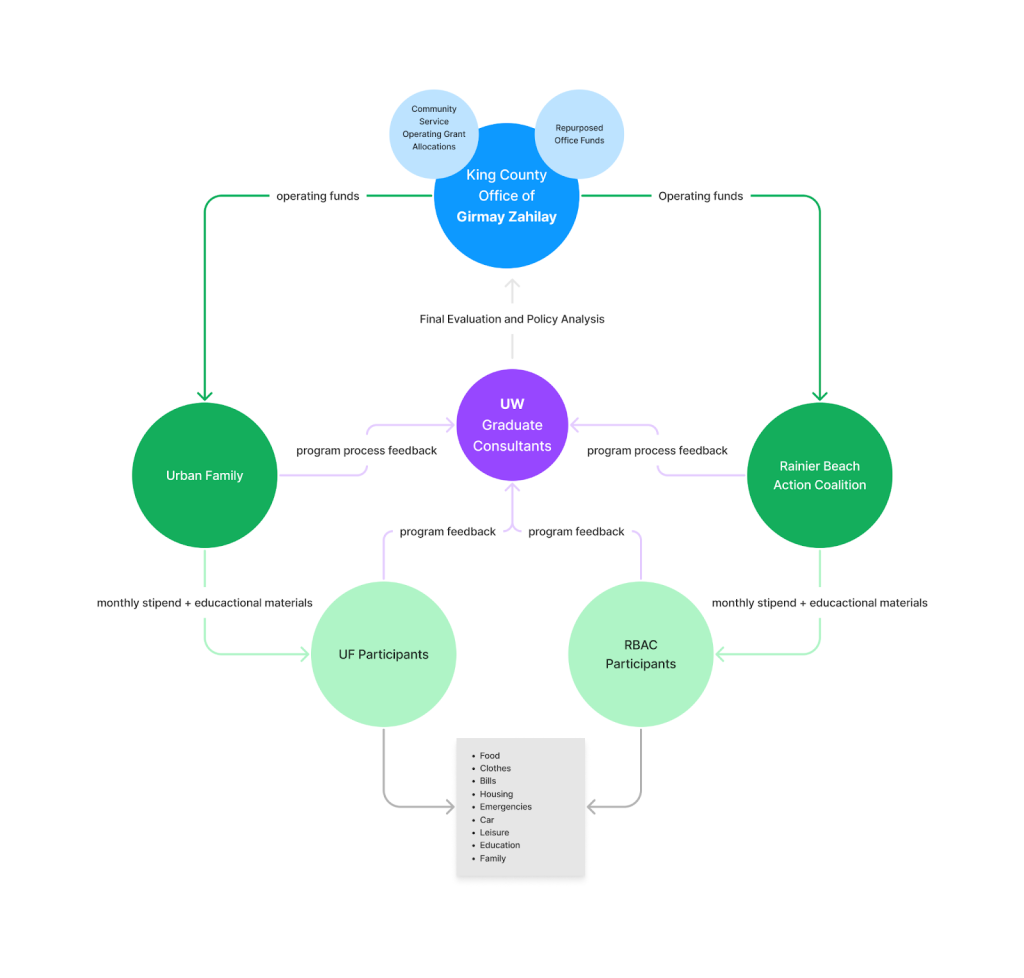

In 2020, King County Councilmember Girmay Zahilay initiated the King County Guaranteed Basic Income Pilot program, which was funded by community service operating grant allocations and repurposed office funds. These funds were administered to the Rainier Beach Action Coalition, and Urban Family, two community-based organizations (CBOs) based in South King County. For the duration of a year, these funds allowed for $1,000 payments to each GBI participant, five from each CBO for a total of ten participants. Over the next year, I was part of a graduate student research team that tracked the pilot program’s progress and wrote a research report analyzing its findings. What we learned along the way showed us the promise of GBI to improve people’s lives.

As a long-time native of South King County, I was immensely moved by the stories and backgrounds of all the participants who were gracious enough to share their experiences with me and my team. While only an hour at the time, the interviews we conducted not only allowed me to hear of the great ways that the funds and materials positively impacted their financial literacy, mental health, and wellbeing, they also allowed me to form a personal connection with these households and their lived experiences.

GBI is a concept that has been garnering attention in recent years both in the media and public policy circles. In GBI programs, unrestricted financial assistance is provided to participants, which runs counter to the usual government assistance approach which supplies funds for specific items like food or rent. Proponents of GBI point to the fact that many households who rely on those programs are unequipped to handle an unexpected expense or emergency, which can lead to devastating consequences.

On the other hand, studies have shown that people living in poverty who receive unrestricted funds are not only better able to handle these unforeseen hardships, they are also more likely to find employment, have better health outcomes, and experience overall better financial stability. GBI programs seek to build on those findings to provide financial assistance in a way that allows individuals autonomy in their own budgets.

The CBOs were given full authority in their design and implementation of the GBI process, as they have a comprehensive and historic understanding of what their clients and community needs, as well as have built trust with their people. Both organizations serve King County District 2, which stretches from Seattle’s southern boundary to the Laurelhurst Neighborhood’s northern border. Gentrification has driven countless households, disproportionately Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, to the southern area of King the County, historically known as the home of its most diverse population.

Councilmember Zahilay also requested a research study for the pilot with the future intention of creating a larger GBI program in King County. I, along with three other students (Chandler Gayton, Annalise Quach, and Monea Kerr), was selected to conduct a series of reports on the pilot program for our Masters of Public Administration Capstone project administered through the UW Evans School of Public Policy.

Our report, which can be read in full here, followed the GBI program from implementation to conclusion. Along the way we collected information about participants’ experiences, conducted a policy analysis to determine the best course of operation for future GBI programs in King County, and synthesized a final program evaluation using feedback from both GBI participants and staff.

Program model and participant experience

The GBI stipends were distributed differently by each CBO, with RBAC using direct deposit and Urban Family using checks. Aside from stipends, each CBO delivered monthly educational materials and feedback forms to each participating family. The educational materials varied in themes each month, from disaster preparedness, and credit score, to even mental health, wellness, and carbon monoxide poisoning. The purpose of the educational materials was to encourage financial literacy, provide assistance in addition to stipend distribution, and gain insight into any operational improvements that could benefit participants.

Each participant mentioned the following spending trends: using GBI stipends to pay for rent and bills; establishing and adding to savings accounts; and spending on basic necessities like food, clothes, and hygiene products. When asked about purchasing goods, one of the participants highlighted their shopping experience:

“Before we got those funds, the most things we were struggling with was just getting our needs- like bathroom soap, laundry soap, laundry detergent, toothpaste, brushes, like those were really hard for us to get, but now it’s like we’re able to restock every week, buy a whole bunch of them and won’t buy any for 1 month because we’ve bought a bunch of them…That is the greatest blessing, to be honest.”

GBI PARTICIPANT

Many participants were able to change their habits for the better. One participant was able to buy fruits and veggies from the organic section, buy fresh salmon, and incorporate healthier cooking habits into their life. In addition, participants were able to spend more quality time with their loved ones: one participant stated that their family was able to go to a buffet for the first time, go to amusement parks and see the circus, all thanks to the pilot program. This highlights how providing unrestricted cash assistance goes beyond providing money for basic necessities by also giving families access to items of leisure and pleasure that greatly improve their quality of life, as one participant poignantly described.

“I just bought a new Christmas tree that I bought this year. [GBI] makes me happier because I’m allowed to do doing things that I would be stressing about prior.”

GBI PARTICIPANT

Evaluation and policy analysis

Each participant was pleased with their CBO’s engagement and work and shared that they read and watched the educational materials provided by the CBOs every month. Additionally, all participants reported returning to some content regularly, most notably the budgeting information from the first month. At the end of the pilot, numerous participants were greatly interested in the possibility of furthering it, or receiving assistance after the pilot’s conclusion, specifically mentioning that the GBI program duration was not long enough to help them out of their financial positions.

Our team’s policy analysis of the GBI program was meant to examine key elements of the pilot, and determine strengths and areas of improvement, so that potential future iterations of the GBI program can reap greater benefits.

Overall, we learned that specificity is key to the success of a GBI program’s success. Our recommendation is that in a larger or extended GBI program in King County, elements such as the funding source, stipend amount, the target population (youth/young adults, homeless, foster care, veterans, etc), and more must be tailored to the specific aims of the program’s unique goals such as providing transitional services, building generational wealth for underserved populations, decrease poverty, etc.

However, each of these elements has important trade-offs that must be kept into consideration, such as sustainability, public support, and how public dollars can be used for programs, or flexibility. Various combinations of stipend amount and duration used by other GBI programs have also illustrated the possibilities for different program-specific goals.

Final Evaluation

Each participant was grateful for the opportunity to have been selected for the program. However, the majority of respondents hoped for a longer-duration pilot. The educational materials provided helped participants with easing into the conclusion. GBI funds provided no adverse effects on other government assistance that participants received (SNAP, TANF, Housing Choice Vouchers). Participants consistently shared that the guidance and leadership the CBOs provided made the process easier, specifically mentioning trust and familiarity, and many of them would prefer a continued relationship with their CBO for future GBI installments:

“There’s a personal relationship that the county wouldn’t be able to replicate. It feels authentic and helpful. If it were operated through the county, it would be awkward and invasive to discuss personal finances. [CBO] has been transparent about the intentions of the program from the beginning.”

GBI PARTICIPANT

At the conclusion of the program, each participant reported decreased levels of stress, having a better understanding of budgeting, and becoming more financially literate. One of the GBI participants iterated how strong a source of relief the funds were for their family:

“The funds took that extra comfort- something that’s been struggling on your chest, the funds were able to just lift that up” The funds helped us a lot – it was a huge blessing, I would just thank the Lord every time it dropped.”

GBI PARTICIPANT

In my work as a researcher, I found myself cheering and celebrating their financial and personal achievements along with them, as well as empathizing and sharing grief during personal emergencies or when systematic structures fail them. While I am glad that my team and I have completed such an astounding accomplishment, especially during the time of a global pandemic, it is rather bittersweet knowing that the completion of this project means the end of our regular update meetings.

Other team members were similarly impressed by how well the pilot went and touched by how it impacted participants’ lives. “Working as staff to CM Zahilay in addition to being on the capstone, the process seemed very quick. I was amazed that the CBOs were able to implement and run an entire GBI program with no direction other than, ‘give the dollars to those who need them most.’ Both RBAC and Urban Family did this in less than three months. It confirmed what many already know: that the community knows what’s best for their community,” said Chandler Gayton, a fellow graduate consultant. “Seeing and witnessing the joy/happiness/appreciation that came from recipients is something I will never forget and I am eternally grateful for the part we were able to play during the entire process.”

Seeing the ways in which these families were affected by a year-long program pilot, we cannot help but wonder about the impact that this program could have if expanded for a longer term, or if granted to all King County residents. Also, while my team and I acknowledge the financial constraints of expanding a GBI program to a larger section of King County, we hope that these experiences and evaluations show insight into the impact of this program on the participants, as well as their families and community in South King County.

Devoni Rose Whitehead (Guest Contributor)

Devoni Whitehead (she/siya) earned her MPA from the UW Evans School of Public Policy and Governance where she specialized in Social Policy. Devoni is committed to not only elevating the voices of her local BIPOC community, but also to deconstructing oppressive systems that continue to marginalize, isolate, and disenfranchise them in the first place. She currently works as a Research Associate for Community & Economic Development at Big Water Consulting.