Bainbridge Island, a 65-square-mile city of about 25,000 residents boasting hourly ferry service to and from Seattle, is an incredibly popular destination for tourists visiting the Puget Sound region. But it can be difficult to navigate the island without a car. The sidewalk network on the island is incomplete, and it only boasts 10 miles of bike facilities compared to its 210 miles of roadways. Only one bike corridor, the incomplete Sound to Olympics trail, has been rated an all-ages-and-abilities facility.

In 2018, the City of Bainbridge Island put forward a seven-year, $15 million levy that would have funded improved bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, but that measure was rejected by voters by around nine points. A primary criticism of the measure was that the City wasn’t committing to funding any specific projects, just several broad categories of projects. Following the defeat, the City recalibrated and spent the next few years coming up with a new plan to increase multimodal infrastructure on the island that it hopes will have more community buy-in.

The result is Bainbridge’s Sustainable Transportation Plan, which the City Council voted to adopt this past March. At the heart of the plan is a list of projects that would connect the commercial centers around the island with high-quality walking and biking infrastructure, “with the goal of being able to send your ten-year-old on a bicycle to ride between these centers and have them feel safe the whole way,” as Chris Wierzbicki, Bainbridge Island’s public works director told the council earlier this year.

One of the largest proponents of added bike and pedestrian infrastructure on the Bainbridge City Council is Councilmember Leslie Schneider, who was appointed to fill a vacant seat in 2018 and reelected in 2019. Schneider, an enthusiastic supporter of the Sustainable Transportation Plan, has articulated a clear link between shifting people to sustainable modes of transportation and meeting the city’s goals around emissions reductions.

“The big win here is, I really feel that the community that has been engaged on this has really circled the wagons on all-ages, all-abilities facilities… and I really feel like there’s a lot of consensus around the fact that we do need them. The counter to that is we recognize that wider roads with a white stripe is not enough protection for trying to get new cyclists interested and engaged in shifting modes,” Schneider said at a discussion of the Sustainable Transportation Plan earlier this year.

According to the City, the “Connecting Centers” proposal would cost $31 million over a six-year period. Some of that money is already on hand, and the council is looking at additional revenue sources to get all of the projects funded. Last month, they voted to make a $30 vehicle license fee that was set to expire permanent, and several councilmembers have expressed a desire to increase the amount to $40 or even $50 and bond against it, providing up-front funding to get the network built on time.

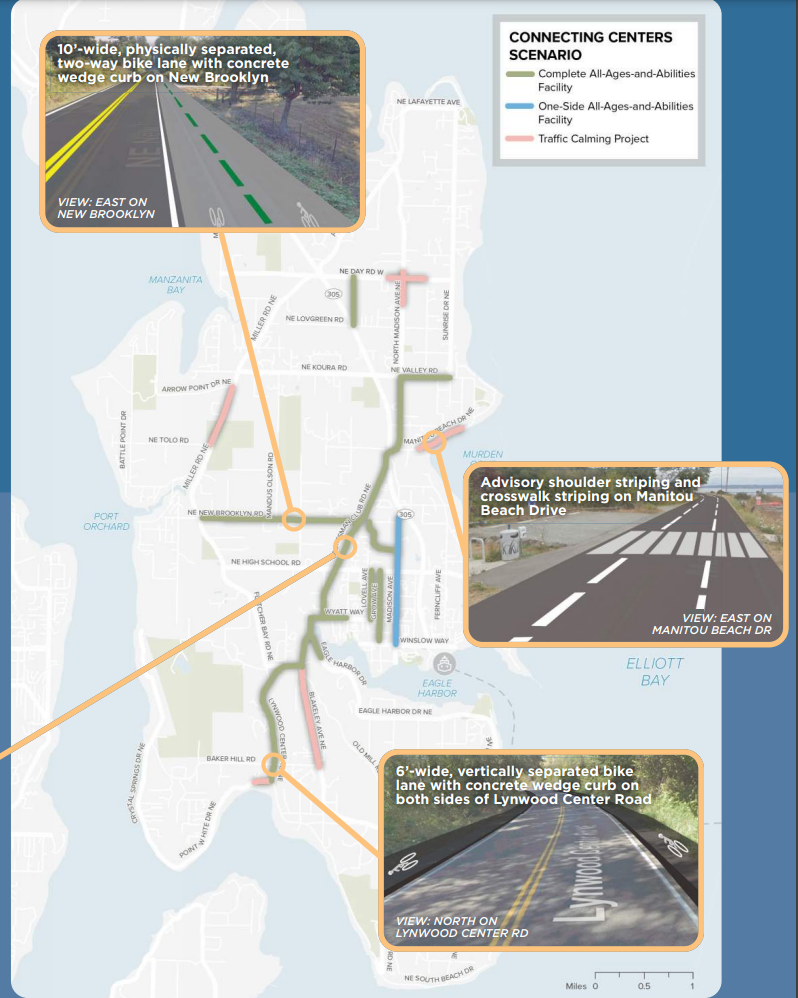

The Connecting Centers network

The Connecting Centers network would combine 10 individual projects to create a “spine of high-quality infrastructure” to the main commercial districts on Bainbridge Island. People on bikes would be able to access Lynwood Center, with its theater and grocery store, to the south and the Rolling Bay, where the Bainbridge Island municipal court is located, to the north of Winslow. Most of these bike corridors would be created by building a raised bike lane alongside the existing roadway or a separate two-way bike lane alongside the road.

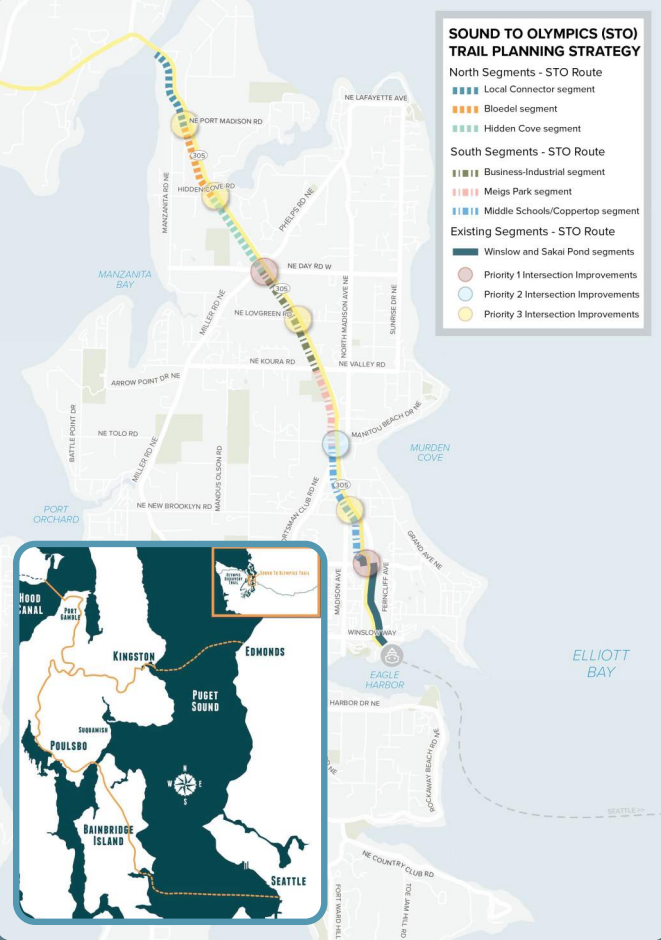

Another key component of Bainbridge’s planned bike network, and the regional network, is the Sound to Olympics trail. Envisioned as a complete trail connecting the Washington State Ferries terminal in Winslow and the Agate Pass bridge to the rest of Kistap County following SR 305. Right now a short segment of the trail exists on the Winslow end, but the rest remains to be built. Bainbridge is planning the next segments of the trail to be competitive for state and federal grant dollars.

This week, Governor Jay Inslee biked the current stretch of the Sound to Olympics Trail as the Leafline Trails Coalition launched their vision map, which seeks to plan to create 400 miles of trails throughout the four-county central Puget Sound to add onto the existing 500 miles of trails, creating a full 900 mile trail network. Opening up access to the rest of the county, the trail looks poised to be prioritized by elected officials around the region as a connection that should be urgently completed.

There’s also a public transit element to the Sustainable Transportation Plan. Envisioned is both a free circulator bus in the Winslow area, but also a free circulator that serves the entire island. Finding a permanent funding source for this could provide challenging, however, since Kitsap Transit seeks to provide service across the entire county and it will likely prioritize more transit-dependent communities for investment ahead of Bainbridge Island.

All of these elements are intended to come together to allow people to experience Bainbridge outside a windshield. “I’m excited to see not only that people on the island are using our infrastructure, but also how many visitors can we convince to not bring their cars on the island,” Councilmember Schneider said before voting to approve the plan.

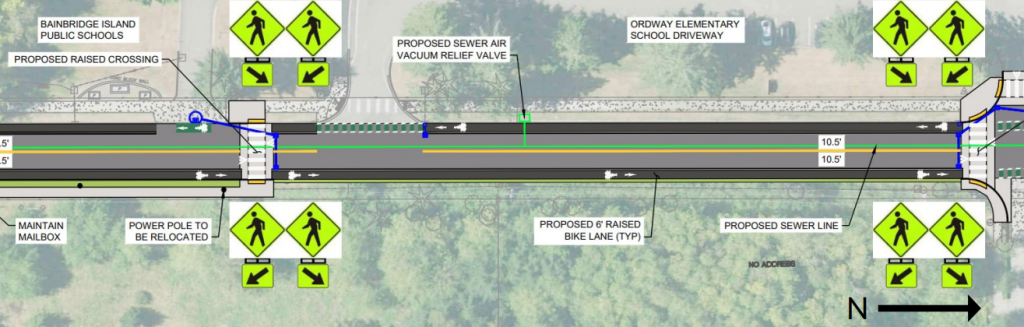

Madison Avenue: Kitsap’s first protected bike lane

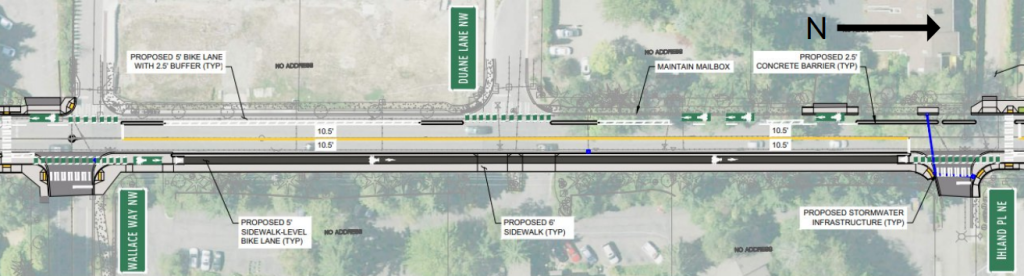

Bainbridge city government is moving ahead with these Connecting Centers projects right now. In May, the City Council voted to move ahead with a project that will overhaul one of the main corridors connecting Winslow with the rest of the island. Madison Avenue, which is home to two schools, the Bainbridge Island public library, and its city hall, would see upgraded sidewalks, and along a central segment, paint bike lanes would be upgraded to raised bike lanes. That separated space for people biking will be the first on-street protected bike lane installed in all of Kitsap County, according to an inventory conducted by the Puget Sound Regional Council.

But the project illustrates the impediments that come from putting plans into action. Apart from the segment in front of the school buildings, the rest of the corridor won’t have full separation for people on bikes: to the south of the schools, only one side will be separated, the other direction will be buffered. Further south, where traffic volumes are even higher as riders approach Winslow, the paint bike lanes aren’t planned to be upgraded at all, just made more visible.

Some councilmembers, including Schneider, expressed disappointment that the facility wasn’t going to be built to full all-ages-and-abilities standards. The primary driver behind the current design is money. Council President Joe Deets asked Wierzbicki before a vote on the project what it would have cost to build the whole project to AAA standards: the answer was an additional $1 million to $1.5 million dollars, which would have to come from other projects.

Wierzbicki described the design moving forward as a “pragmatic compromise” that had to be made, and defended the design with the fact that the roads already have existing bike facilities, but not those at the highest quality standards. It will remain to be, however, see how much pragmatic compromise will have to be made with the rest of the proposed network in the coming years.

Bainbridge Island is one of Kitsap County’s wealthiest communities, and so its ability to leverage resources to create these projects is much greater than other nearby cities or unincorporated areas. Madison Avenue will be the first on-street protected bike lane in the entire county, and the vast majority of existing bike infrastructure will continue to consist of painted or just extra shoulders on the side of frequently hostile streets. Upgrading these facilities is an urgent matter. Earlier this year, John Skubic, a 63-year-old Poulsbo resident, was killed while biking on a street without bike infrastructure by a driver who struck him from behind.

It’s inspiring to see communities with resources like Bainbridge Island take the initiative on decarbonizing transportation by making it more attractive and easier to get around without a car. But ensuring that everyone, including people who have been priced out of areas like Bainbridge, can also have access to safe facilities is also critical. The issue of economic disparity in pedestrian and bike investments is far from unique to Kitsap County, of course. However, this stark example shows how important it is for the state government to continue to fund investments in walking and biking. In the meantime, Bainbridge Island is trying to show how it’s done, undoubtedly with some future stumbles to come.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.