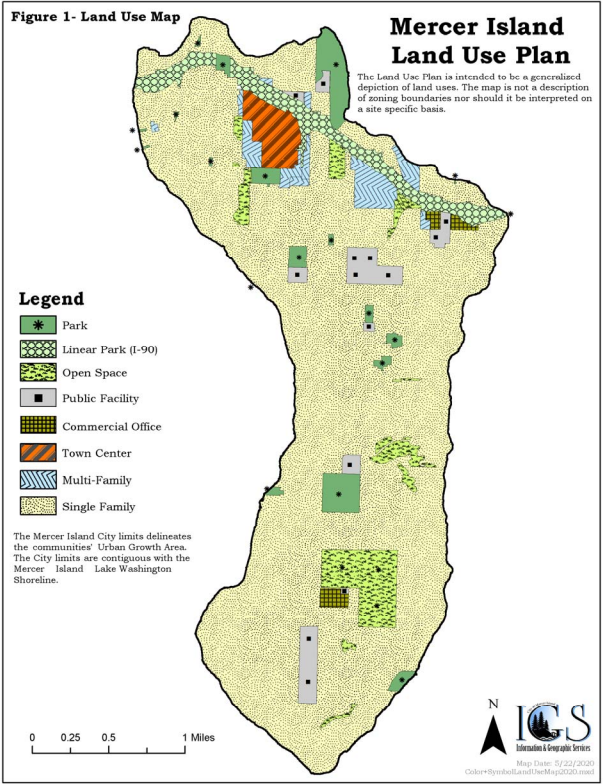

On Tuesday evening, Mercer Island’s City Council is poised to renew a moratorium that prevents the redevelopment of parcels in the southeast corner of the city’s Town Center, one of the only areas on the 12.9 square mile island where relatively dense, mixed-use housing is allowed. The ordinance, originally passed as a six-month emergency moratorium in June 2020, has since been extended three times to last nearly two years — and will likely endure for a few months more.

The moratorium’s intent was to give the city’s Planning Commission, staff, and Council time to evaluate requirements for commercial space throughout the Town Center, a method seen as a way to address the loss of retail square footage in the city. However, an actual retail demand analysis was not to be completed until ten months after the moratorium’s declaration. In February of 2022 — over a year and a half after the original ordinance was approved — planning commissioners submitted a brief to Council asking for a clearly expressed problem statement to justify the whole endeavor.

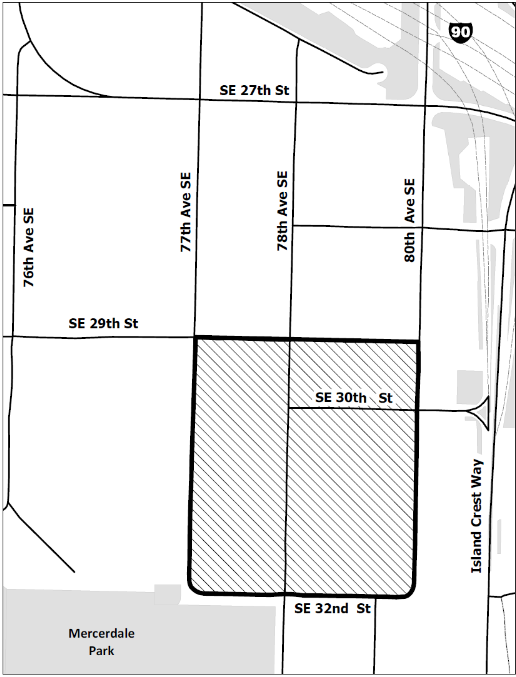

All the while, 16 acres of real estate that’s mere minutes from a soon-to-open light rail station has been restricted from redevelopment, out of dramatic fear that inconsistent development could result in “visual blight, economic hardship, and poor infrastructure design that pose harm to public health, safety, property, and welfare.”

The opening of the Northgate Link extension in 2021 coincided with a major wave of housing growth nears the stations, but a similar wave doesn’t seem to coming for many of the ten East Link stations. The Urbanist tallied more than 6,000 homes recently completed or in development in the University District, more than 4,000 homes in Northgate, and 3,300 homes and counting in Roosevelt. Restrictive zoning appears to the main culprit, as housing demand is skyhigh on the Eastside. “Mercer Island has nothing more visionary than a small area of three- to five-story buildings planned near its station,” The Urbanist‘s Stephen Fesler concluded in his look at East Link’s limited transit-oriented development progress thus far. In contrast, many other cities are zoning for at least seven-story buildings near rapid transit stations, if not highrises too.

Even some suburbs that aren’t getting light rail are doing far more than Mercer Island with choice sites like the one under the moratorium. For example, Woodinville is planning to add 1,200 homes and 400,000 square feet of commercial space in a 19-acre Molbak’s site and replacing the Molbak’s garden store in the process. Meanwhile, Mercer Island seems to have little regard for delivering housing adjacent to a light rail station, let alone the rest of the island, and is hung up on micro-managing retail land use regulations.

In 2015, Mercer Island was under an island-wide residential development moratorium that barred subdividing lots, which tend to quite large. The minimum lot size in the city’s residential neighborhoods is 8,400 square feet, and many are larger.

How We Got Here

Per Mercer Island’s land use code, developments in the city’s Town Center that are north of SE 29th Street are required to provide streetfront retail to some degree. Similarly-zoned parcels south of SE 29th Street are allowed to, but not required to, provide such commercial space. These regulations have largely contributed to the city’s current urban form, which is largely comprised of mixed use retail and residential buildings in the north end of the Town Center and more traditional (i.e. more parking-oriented) retail in the southern end.

As part of a suite of recommendations from a July 2021 meeting, City Council recommended that these streetfront retail requirements be extended to SE 30th Street and southern portions of 78th Avenue SE. More controversially, Council recommended the creation of a “No Net Loss” provision to certain parcels that had been redeveloped since 2005. This would mean that, if redeveloped again, these parcels would be required to maintain the same level of commercial retail space that they had previously provided. Properties that had not yet redeveloped would instead be required to provide a minimum commercial floor area ratio (FAR) of 0.2623, a figure calculated through a complicated seven-step process based upon the city’s existing and projected retail space. These recommendations were forwarded onto the Planning Commission for consideration, with the intent for the provisions to return to Council in time for approval before the moratorium would need to be renewed again in December.

However, the Planning Commission did not present a unified front on its recommendations. Commissioners like Mike Murphy, who drafted a brief on October 18th, took issue with the new minimum FAR requirement, claiming that the provision had no precedent in other jurisdictions. Murphy’s brief also cited concerns around a lack of parking provisions and potential legal challenges that could result from the imposition of a “no net loss” clause.

In her own counter-memo on November 3rd, Commissioner Carolyn Boatsman advocated for passing the Council’s suggestions with minor amendments, as “the draft ordinance… would make measurable and significant progress towards the limited goal” of “protecting and expanding Mercer Island’s retail sector.” Per her memo, Boatsman believed that the commission was getting too into the weeds and was trying to regulate for things that market forces would determine. However, the commission ultimately voted to decline to recommend the Council’s proposed ordinance 5-1, with Boatsman providing the sole dissenting vote. This meant that Council was pressured to take another stab at the ordinance and that the moratorium would need to be extended again.

After amendments from Council in December to allow any parcel to comply with either the minimum FAR or no net loss requirement, the ordinance found its way back to commissioners earlier this year. However, a significant number of residents and property owners came to testify for the first time in the whole process against the proposal, claiming that the proposed ordinance would make redevelopment more difficult and asking that more outreach be conducted. A recommendation against Council’s proposed ordinance was unanimous this time, with commissioners asking Council for the aforementioned problem statement as well as clearer outreach to the community.

At a March meeting however, Council directed staff to continue work on the ordinance with only minor amendments from their previous proposal, but they did not direct the ordinance be sent back to the Planning Commission for further review. The final proposal is expected to come back to Council later this year before their summer recess, at which time the body would rescind the moratorium.

This brings us to the upcoming Tuesday meeting, where Council is likely to extend the moratorium for an additional six months. After 12 City Council meetings, five Planning Commission meetings, two public hearings, and two years of staff’s time, the end might finally be in sight to the endeavor to bring more retail to Mercer Island.

A Solution in Search of a Problem

The April 2021 commercial demand analysis commissioned by the city does show a loss of 11% of the city’s retail space from 2010 until 2021. However, an updated version of that same study predicts that Mercer Island’s meager growth targets of 2,720 new residents by 2044 will produce just over 34,000 square feet of additional retail space demand — placing the total amount of retail square footage below what was present in 2010. This now years-long process, which had garnered very little oral testimony from property owners or members of the public until earlier this year, therefore seems to be an extensive use of time and resources for very little payoff.

To be fair, the small projections in both retail and population increases do continue a long legacy of limited growth for the city. In the last decade, Mercer Island has added just 375 new multifamily units across two developments. With the overwhelming majority of the island zoned for big lot single-family homes, the Town Center represents city leaders’ key target for new growth — but Mercer Island is simply not doing enough to take advantage of the opportunity that upcoming light rail represents.

Instead of facilitating significant work to increase density and affordable housing on an island whose median home price has topped $2.3 million dollars, leaders have frequently expressed their desire to limit growth in the city. During the height of the State legislative session, Mayor Salim Nice wrote a letter to the 41st Legislative District delegation asking them to oppose House Bill 1782, which would have allowed for more missing middle housing types in single-family areas. Rep. Tana Senn, who resides in a rapidly appreciating Mercer Island single family home and represents the 41st, helped water down the bill and authored the amendment shrinking the baseline requirement for sixplex zoning near frequent transit to fourplex zoning.

At a City Council meeting earlier this month, Mayor Nice seemingly cited the potential for increased total emissions as an argument against the city accepting further growth. Nice suggested that Mercer Island had already accepted more than its fair share of growth, stating that the island’s population was already above where it was “supposed to have been” in 2035 in one set of growth projections.

Whether intentional or not, the immense opportunity cost of devoting significant staff time and resources towards the preservation of retail space instead of advancing housing work serves to entrench the limited growth that has contributed to the city’s expensive status quo. Instead of prioritizing the needs of a “disappearing” retail sector, city leaders would be well-served to prioritize growing Mercer Island’s population so that this sector could be supported by market forces.

Unfortunately, that will have to be a lesson for next time, as there’s no way to get back the past two years that could have been spent taking more meaningful housing action near light rail. But, as many have come to realize, the second best time to pass widespread housing reforms is now.

Chris Randels is the founder and director of Complete Streets Bellevue, an advocacy organization looking to make it easier for people to get around Bellevue without a car. Chris lived in the Lake Hills neighborhood for nearly a decade and cares about reducing emissions and improving safety in the Eastside's largest city.