The City of Seattle declared this week “Affordable Housing Week” as part of an annual tradition, with the Housing Development Consortium hosting events highlighting affordable housing efforts both planned and underway. Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda sponsored the resolution at city council, and she is also the driving force behind the Jumpstart Seattle progressive payroll tax that is set to become the city’s largest source of funding for affordable housing.

“I’m especially excited about this year’s Affordable Housing Week proclamation because we have a lot of work to do in the horizon, but we’ve also been able to celebrate a tremendous amount of wins in the last few years,” Mosqueda said during the weekly council briefing on Monday, noting Jumpstart revenues would continue to increase in coming years.

The first year of Jumpstart spending plan was used to backfill holes in Mayor Jenny Durkan’s budget, but the long-term spending plan sets aside two-thirds of revenue for affordable housing. As of April when projections were again revised up, Jumpstart is projected to pull in about $277 million this year, and the tax prevailed in its first legal challenge from the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce.

Paired with increasing proceeds from Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program and the Seattle Housing Levy, Jumpstart is poised to continue to boost the City’s affordable housing awards over coming years. This has already fueled a significant uptick in affordable housing production from the City’s nonprofit partners.

“There are over 5,400 new affordable units currently under development, with 4,000 of those opening in this upcoming year,” Mosqueda said. “That’s an incredible investment.”

MHA posts record-setting $76 million haul in 2021

The Seattle Office of Housing revealed that last year MHA raised almost $76 million in fees and produced 95 rent-capped units on-site in its annual housing reports released earlier this month. “Both metrics increased from 2020, when Covid-19 disrupted the market and when the totals were $68 million in fees and 21 on-site units,” noted Daniel Beekman of The Seattle Times, who covered the news earlier this week. From its inception through the end of 2021, MHA has pulled in $171.4 million. Even with the recent surge in production, only about 9% of Seattle’s housing stock is composed of affordable rent-restricted homes.

The Seattle Office of Housing said the 2021 MHA haul will fund more than 900 affordable homes (past projects are laid out in its investment report). The department assumes $80,000 of City support per unit on average, Beekman noted. A typical affordable home may cost about four times that much to build, but affordable housing builders typically braid that City award with state grants, federal support (often led by Low Income Housing Tax Credits), philanthropic support, and loans, which are sometimes offered at below-market rates via local corporate largesse or government programs.

The increase in affordable housing funding is well-timed because building costs are skyrocketing, and the need is also increasing as many working class residents find themselves priced out of the regional housing market. Single family home prices saw unprecedented one-year jumps last year, often in the 20% to 33% range, particularly on the Eastside, although formerly moderately priced cities like Lynnwood, Kent, and Renton also saw huge jumps. The extra funding will help keep up with climbing building costs, but there is also a great need to ramp up production.

“Over the last five years, building costs are up about 24%,” HDC executive director Patience Malaba said at the Affordable Housing Week kickoff event on Monday. She added that interest rates and land costs were up, too.

While calling for more resources for existing providers, the Housing Development Consortium has opposed a recent effort to explore a social housing model with publicly owned land, mixed-income buildings, and greater tenant control of buildings. Last month, HDC came out against Initiative 135, which creates a public development authority to build social housing. The Urbanist dug into that proposal from House Our Neighbors in March.

“We welcome innovation and share many of the same values as the backers of the Initiative. These include the belief that every person deserves a safe, affordable home, and that we need a scale of public investment in affordable housing that lives up to this value,” HDC said in its statement. “However, this Initiative would divert scarce public resources toward the creation of a new bureaucracy and is a distraction from what should be our priority as a City — greatly increasing funding for affordable housing to meet the scale of the need.”

That ballot measure will go to voters in November if the House Our Neighbors campaign is able to collect enough signatures.

Need for zoning reform

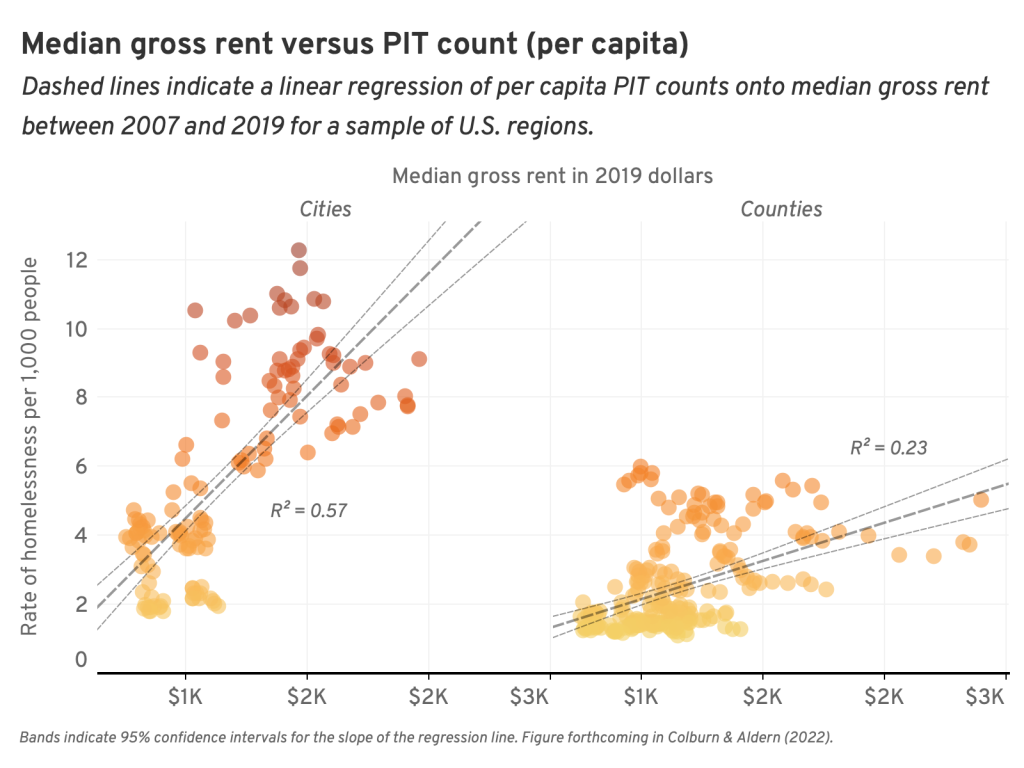

While social housing was earning some pushback, panelists at the HDC kickoff event agreed zoning changes were needed to allow more multifamily housing across Seattle. Panelists Mosqueda, Malaba, King County Councilmember Girmay Zahilay, and Gregg Coburn, who is author of Homelessness is a Housing Problem, all agreed on that point.

“We need to address this extremely restrictive zoning policies that we have at the local level,” Zahilay said. “Seventy-five percent of the residential land in Seattle, for example, is zoned for detached single family homes. I recently took a trip to Germany… and there are so many places that are shocked that we have zoning the way we do. You can nice-looking, quaint, quiet neighborhood that have duplexes and triplexes. That’s not a hard thing to do. And yet we still have these burdens on the ability to build dense, walkable neighborhoods. We have a big role in addressing these issues.”

“It starts with zoning,” Mosqueda agreed. “We must rezone our city and make sure we have a truly inclusive Seattle.”

The panel also stressed the racial equity implications of housing policies past and present and the negative impact of the workers not being able to afford to live in the cities where they work or have built communities.

“Right now we are third highest mega-commuter city in the entire country, meaning people are spending an hour or two hours in their cars just to get to work,” Mosqueda said. “This is not good for the health of our communities; it’s not good for the health of our planet, and it’s not good for the health of our economy, either.”

To address the housing crisis with a racial equity focus, Mosqueda called more affordable housing, both rental and homeownership options at all income levels, and “to truly densifying how folks can live across our city.” Seattle also added a community preference policy and an affirmative marketing program to help increase disadvantaged group’s access to the affordable homes the City is funding, such as Black residents who have been displaced out of the Central District.

That zoning fight is set to take place when Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan is updated in 2024, and Mosqueda encouraged people to participate in that process as planning and outreach picks up in 2023. In the meantime, she encouraged advocates to push for housing funding. Coburn called for a large-scale “Marshall Plan” for housing and warned against nibbling around the edges since housing is such a massive problem interconnected with other crises. His book argues the solving homelessness crisis first and foremost stems from the housing shortage despite efforts to brand homeless people as addicts, criminals, and/or lazy pariahs undeserving of help and in need of stern hand and punitive measures.

Malaba concluded the panel with a reminder that the Seattle Housing Levy is up for renewal in 2023, and hinted at a push to increase its size. The 2016 levy is raising $290 million over seven years. Seattle has voted yes on every housing levy since the first was put to voters in 1981.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.