With election season already around the corner, cities that want their residents to vote on November ballot measures are moving to finish necessary planning work by an August filing deadline. Since January, Redmond has been leading engagement on a new public safety levy that would increase total annual funding for its police and fire departments by $10.4 million. The proposal, which would levy a $0.34 property tax increase per $1,000 assessed value ($340 annually on a $1 million home), would fund:

- 17 new firefighter full-time employees (FTEs) to staff Fire Stations #16 and #17, at $2.9 million,

- 12 new police officers, at $1.98 million,

- 5 FTEs for the support and maintenance of a new police body-worn camera program, at $935,000,

- 6 mental health specialists (including one mental health professional and five social workers/case managers) under the police department at $688,000, and

- An additional FTE and expanded services for the fire department’s Mobile Integrated Health program, at $360,000.

The remaining $3.5 million would go towards retaining 18 firefighters and 17 police officers that were funded by a similar levy in 2007. Because of inflation, city officials say the previously approved levy is no longer sufficient to retain these positions and additional funding is needed. The final proposal is the product of a four-month outreach process, which included a statistically-valid public survey, a hybrid community meeting hosted at City Hall, an online feedback portal, and a ten-member volunteer “Sounding Board” composed of Redmond residents.

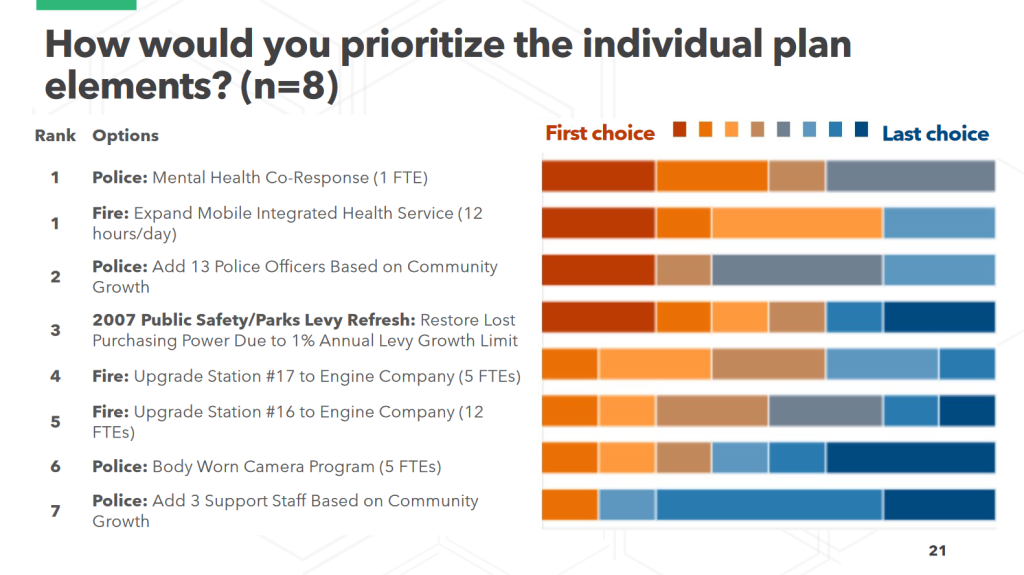

Community feedback, in particular comments from the Sounding Board, did seem to push the city to redirect more funding towards alternative responses than what was initially planned. Before the above proposal was first presented to community members at the May 9th Sounding Board meeting, the city had planned to fund 13 police officers and only one mental health professional, plus an additional three support staff for IT and administrative work. At Tuesday’s briefing to City Council, Police Chief Darrell Lowe explained how funds for the three support staff and one commissioned officer could be repurposed to fund five licensed clinical social workers and/or case managers, which reflected the highest priority of Sounding Board members.

These mental health positions, who would primarily respond with police officers but could provide follow-up support without an officer, build upon Redmond’s current co-responder model. In 2018, RPD hired MHP Susie Kroll as a co-responder to calls which could benefit from “social service connections, referrals, de-escalation, and assessment for behavioral health concerns.” Kroll, who also teaches de-escalation and crisis response at the Washington Police Academy, appears fully supportive of the co-responder model and the institution of policing in general. A photograph of her in a bulletproof tactical vest was photoshopped by the City of Redmond to remove a Thin Blue Line flag, presumably due to the flag’s conception as a response to the Black Lives Matter movement and its subsequent use by white supremacists and insurrectionists.

For many in the community, investing in alternatives to armed police response means creating a fully separate way to respond to incidents that don’t need a full police response, not adding additional responders in with police. Some cities, like Eugene, Oregon, have accomplished this by implementing a community responder model, which does not rely on armed personnel to respond to social service or crisis calls at all. Chief Lowe specifically referenced Eugene’s CAHOOTS program in his testimony on Tuesday, but noted that the city is not in a position to implement a similar program at this time. However, he said he was not opposed to a community response model and that should one be implemented at a later date, mental health responsibilities could be shifted to that organization at that time.

Redmond has not been spared from incidents of police brutality that such a program can help prevent. At an April City Council meeting, the body settled a $7.5 million wrongful-death lawsuit brought by the family of Andrea Churna, who was killed by Redmond police officers Daniel Mendoza and Evan Barnard in September 2020. Churna was unarmed at the time of her death and had been on the ground prone for three minutes in the presence of half a dozen officers before the two opened fire. Barnard and Mendoza — the latter of whom was previously dismissed from the Whatcom County Sheriff’s Department for poor performance — are both still on patrol with the Redmond Police Department.

The incident likely contributed to the widespread support for body-worn cameras expressed by the community; 88% of those polled in the city’s statistically-valid survey thought they were a “very” or “somewhat important” part of the levy proposal. However, some members of the community raised concern at the high price tag of program implementation, which would cost nearly $1 million annually. At the Tuesday meeting, Councilmember Fields asked if the city’s implementation costs were typical for a department of RPD’s size, to which Chief Lowe responded that it was difficult to compare, as much was dependent on how a city implements their program. He did note that the majority of the $935,000 ask would be devoted to the staffing needed to support the program, including positions in IT and the prosecutor’s office.

In response to a question from Councilmember Anderson, Chief Lowe said that mental health responders are not currently explicitly included in the city’s body-worn cameras policy, but that camera use would “make sense” given that they are personnel out in the field. Councilmember Forsythe, in turn, cautioned Lowe to be mindful of concerns around privacy and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements with mental health professionals wearing body cameras. For example, footage of sensitive healthcare conversations between community members and Redmond’s MHPs might still be subject to the same public disclosure requests that could shed light on instances of police brutality. This illustrates the complications that arise with healthcare professionals responding under the purview of the police department.

Redmond’s Mobile Integrated Health (MIH) unit, which is housed under the fire department and currently focuses on preventing emergencies like falls and connecting residents to services, would increase its availability from 40 to 84 hours/week with levy funding. This part of the levy proposal was popular among both community members and Sounding board members alike, likely because of its healthcare-centered approach to public safety. Redmond Fire Chief Adrian Sheppard was adamant in comments to Councilmember Anderson on Tuesday that he does not foresee a need to increase funding for the program in the near-term beyond what’s proposed in the levy. However, Redmond residents could benefit from a broader mental health crisis response program that’s not housed within the police department, and the MIH program would be a good base to build from.

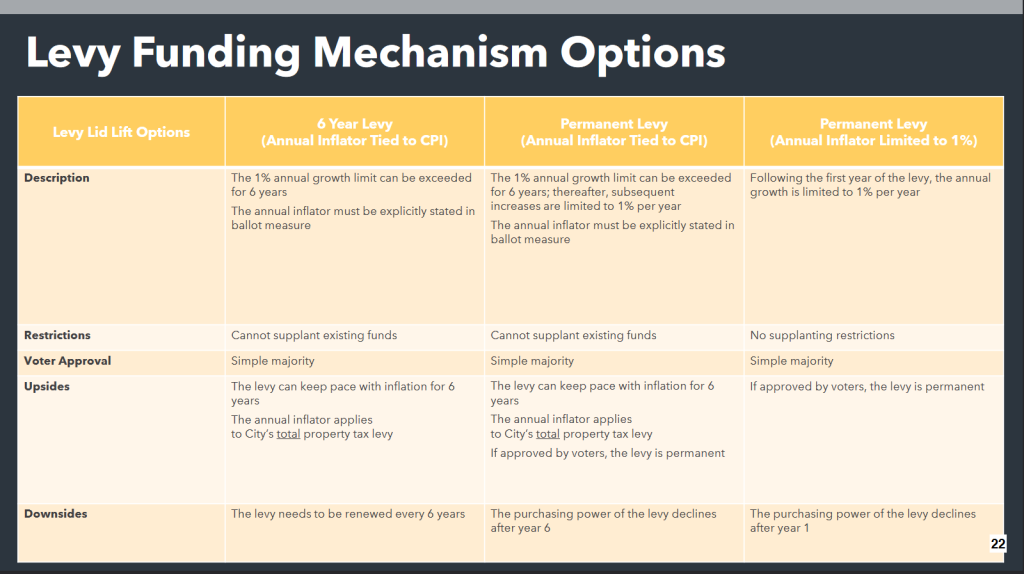

One more important piece must still be debated before Council’s summer decision to place the levy on the November ballot: what type of levy they’ll use. The 2007 levy (described in the last column below) involved a property tax that did not increase with inflation, which has led to decreasing purchasing power over the life of the levy. In contrast, the first two options below involve an inflation-adjusted rate that keeps pace with the Consumer Price Index for six years. The only difference between these two proposals would be their total length: option #1 would only last for six years and would need to be renewed thereafter, but option #2 would last beyond the six years as a permanent levy (but would be limited to 1% annual increases after the six years passes).

All options would only require a simple majority to be approved by voters, but each would present it own slate of electoral risks. Options #1 and #2 would provide the city with more purchasing power, but with the uncertain near-term future of inflation, residents may be uncomfortable supporting a measure that would keep property tax increases in line with it. Option #3 avoids this problem but introduces a new one: because the purchasing power of the levy is reduced, the property tax rate actually has to be set even higher to make up the difference across the life of the levy. For example, staff shared that Option #3 would require a tax rate of $0.432 per assessed $1,000 in value — a 27% increase compared to the rate for Options #1 and #2.

Community engagement will continue throughout the summer and will likely drive Council’s electoral calculus. Staff confirmed Tuesday that they would educate residents on what a positive or negative result would mean for the city, should the Council decide to put the measure on the ballot. Either way, there’s no doubt the decision will significantly impact the future of public safety in Redmond.

Chris Randels is the founder and director of Complete Streets Bellevue, an advocacy organization looking to make it easier for people to get around Bellevue without a car. Chris lived in the Lake Hills neighborhood for nearly a decade and cares about reducing emissions and improving safety in the Eastside's largest city.