App-based electric scooter and bike sharing continues to survive in Seattle, albeit at significantly higher prices than during the bonanza of the launch of free-floating “micromobility” devices. Last month, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) released a report on the first year of the city’s pilot scootershare program. It indicated that injuries, the reason Seattle held off on permitting scooters while other cities gave them the green light, are more regular than we’d like them to be. But the agency has some safety interventions in mind and intends to continue the program, assuming scootershare continues to have the blessing of the Mayor and the city council.

That could be in doubt. KIRO 7 seized on the non-scientific scootershare survey to portray the program as in the midst of a safety crisis, and Councilmember Alex Pedersen, who chairs the transportation committee and voted against the scootershare pilot, was on the same wavelength.

“We really need to prioritize safety before we extend and expand this program with private companies,” Pedersen told KIRO 7. This is an interesting statement from a chair that fought to divert street safety funding toward bridge maintenance in 2021. But even though scooter share is still in a “pilot” phase, there’s not an expiration date for the authority for SDOT to issue permits for their use.

SDOT’s analysis turned up 17 police reports indicating crashes that injured scooter riders, although they were unable to confirm all involved rented scootershare vehicles and not personal scooters. One scooter user has died in the history of Seattle’s program and it was in a collision with a person driving a car. The agency also conducted a broad survey of more than 5,000 scootershare users. Of the 4,578 respondents who answered the injury question, 11% said they had suffered an injury while riding a scooter and about a fifth of those said they sought medical attention for their injury.

Given the high injury rate, it seemed likely selection bias was at play in who responded to SDOT’s open call to complete their survey. SDOT spokesperson Ethan Bergerson confirmed survey was not designed as a random sample and sought to reach people who had mishaps riding scooters to learn how to improve the program.

“This was not designed to be a random sample survey,” Bergerson said in an email. “The invitation was intended to encourage people who had a specific safety [concern] to tell us about their experiences and opinions. The email invitation stated that it was about scooter safety in the subject line, and we described the survey as an opportunity to make their voices heard so that we could improve the safety of this travel option. So it is certainly possible that people who had experienced an injury were more likely to want to tell their story.”

SDOT is planning to finetune the program to promote safety, including with helmet giveaways and safety education programming.

“Since the start of the scooter program, we have implemented a variety of safety features and tactics including requiring companies to build safer scooters, making riders take a safety quiz before their first ride, and creating a built-in speed limit cap of 8 mph on people’s first ride and 15 mph after that,” Bergerson added. “As the scooter program moves forward, we are launching a competitive application process for any scooter companies that want to operate in Seattle. We’re asking companies to provide a specific plan for how they plan to address the challenges identified by our evaluation report, including safety, sidewalk riding, parking obstructions, and creating a helmet distribution plan.”

That re-application process could mean new scooter companies win out if they can make a case that they are safer and also have a handle on the sidewalk clutter issue. The agency did report some progress on the sidewalk clearance compliance front. “Our first quarter of audits in Q4 2020 showed 21% of devices as [sidewalk] obstructions, and by Q3 2021, the number was had decreased to 8%,” SDOT reported.

“Existing scooter companies must re-apply for new permits, and their responses will be evaluated side-by-side with any new companies that apply,” Bergerson added. “Companies with a proven track record of success on safety, compliance, and equity metrics will be considered in the scoring. A maximum of four permits may be granted for the companies with the strongest plans to address these issues.”

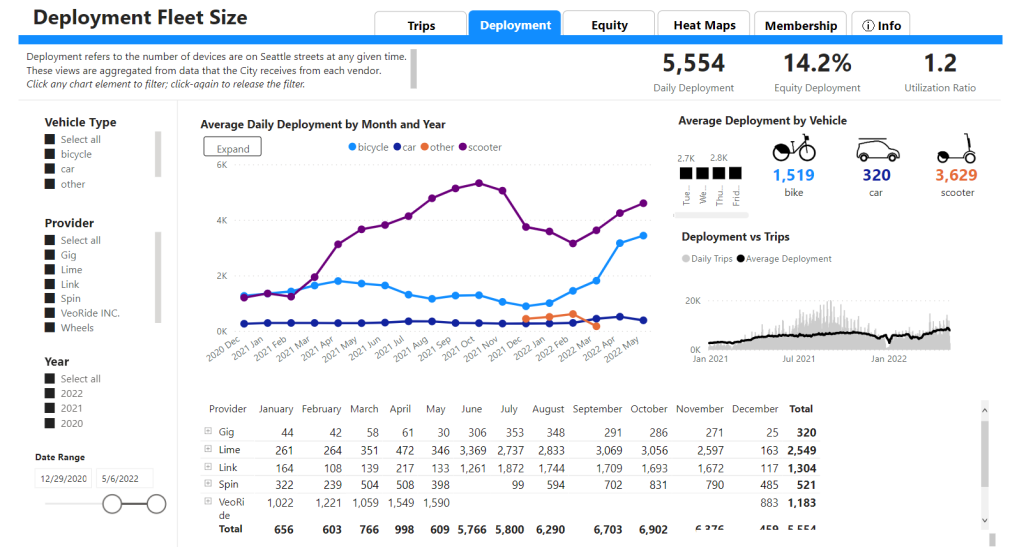

As it stands, the four scooter providers operating in Seattle are Lime, Link, Wheels, and Spin. (Note that Lime was bought out by Uber in 2020.) Over the past year, Lime has logged the most scooter rides, while Link is a close second, according to the dashboard. Lime also leads in the less contested bikeshare space. E-bike deployment has spiked in recent months, with both Veo and Lime ramping up.

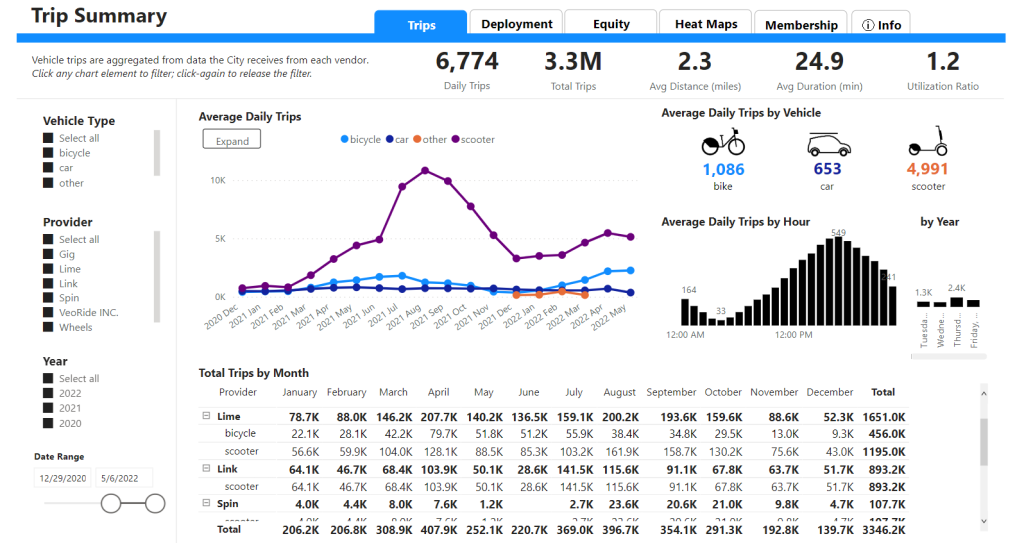

The surge in e-bike deployment is a hopeful sign since policymakers had worried that companies would abandon bikeshare entirely in favor of scootershare, which companies had predicted would attract far more ridership per vehicle (or “utilization ratio,” in industry jargon) and thus revenue. So far scooters have attracted slightly more rides per vehicle: 1.4 versus 0.8. But the gulf doesn’t appear nearly as wide as predicted — perhaps explaining the bike comeback.

Seattle tallied 1.4 million scootershare trips from October 2020 through September 2021, according to SDOT. The agency’s data dashboard reported an average of 2,189 daily bikeshare trips and 5,465 daily scootershare trips in April 2022. The summer months get the highest ridership, as one would expect. In August 2021, the program peaked at an average of 10,826 daily scootershare trips plus 1,238 daily bikeshare trips.

Sharing saga

It’s been quite the saga for bikeshare and scootershare in Seattle.

As recently as 2017, Seattle was contemplating an expansion of the city-run Pronto bikeshare system, which relied on docked bikes. Instead, the Mayor Ed Murray and the Seattle City Council decided to pull the plug, sell off assets, and pivot to a dockless private vendor model.

Initially, many heralded that replacement system as superior in nearly every way, flooded as these companies were with venture capital to roll out thousands of bikes at aggressive loss-leading pricing as low as $1 for 30 minutes. The good times couldn’t roll forever, however. Some bikeshare companies folded, weighted by mounting maintenance costs and lacking a profitable business model. Others introduced e-bikes that were much zippier than the cheap traditional bikes most companies launched with, but also cost significantly more to rent.

Initially, Lime appeared to be winning the bikeshare battle, but soon Jump came in strong, buoyed by more dependable e-bikes and copious capital from Uber. In 2019, Seattle logged 2.2 million bikeshare rides in Seattle — averaging more than 6,000 per day.

By January 2020, only one operator, Jump bikes, was left standing, as Lime temporarily pulled out, citing a lack of profits. In another weird twist, after Uber bought out Lime nationally, they relaunched Lime, with some — but not all — Jump bikes rebranded as Lime. The real competition soon moved to scooters, as companies and advocates rallying to get scootershare legalized. With Seattle greenlighting scootershare pilot in September 2020, more companies entered the market with e-scooters, and Uber-backed Lime also began to shift to scooters, although they continued to offer e-bikes, too.

While Pronto had been criticized for its $6 pricing for rides up to 30 minutes in duration, ultimately the pricing for e-bikes and e-scooters has crept well beyond that. With a $1 unlock fee plus rates hovering around $0.40 per minute on most providers, a 20-minute ride costs about $9 and a 30-minute ride about $13.

Providers do offer a low-income program, such as Link’s Link-Up that provides free rides of up to 20 minutes to riders who have successfully qualified by verifying they belong to another assistance program, such as ORCA Lift or Apple healthcare. However, it does appear there’s a donut hole in the program between those who qualify for free or discounted rides and those well-off enough to afford dropping $10 per ride on the regular. It’s also not clear the low-income program is well publicized.

Helmets, car crashes, and other safety issues

Helmets have been a major point of contention that could complicate expansion of the program. The King County Council recently voted to lift its helmet requirement law, but authorities have still sought to encourage helmet use through a less punitive and hopefully less racially biased system.

SDOT’s survey suggests most scootershare riders do not wear helmets, with about 70% of respondents saying they never, or almost never, wore a helmet while riding a scooter — 40% of respondents said that this was because they did not own a helmet.

“Helmet ownership is a problem that we can help address, and in the future we plan to increase outreach with more riding safety demonstrations and helmet giveaways across Seattle, like this event conducted with East African Community Services last summer,” Bergerson said. “We are also working to strengthen our partnership with Seattle + King County Public Health, and with community organizations like Bike Works, to increase access to free helmets. This past November, we partnered with Seattle Public Schools and Cascade Bike Club to bring back and expand the Let’s Go safety education program for all 3rd to 8th grade Seattle students, including lessons on the importance of helmet safety. Finally, we require scooter vendors to have a helmet distribution plan, including partnering with us to distribute helmets at community events.”

Moreover, SDOT acknowledged its role is also to reduce car speeding and collisions in order to create a safe environment on its streets, including via protected bike facilities. “As a department of transportation, our role is to design a safe system that enhances public health,” Bergerson added. “This means continuing to build out a bicycle network for all ages and abilities, lowering vehicle speeds so we can reduce the frequency and severity of crashes, and engaging with community members. This helps improves safety for everyone, including people riding scooters.”

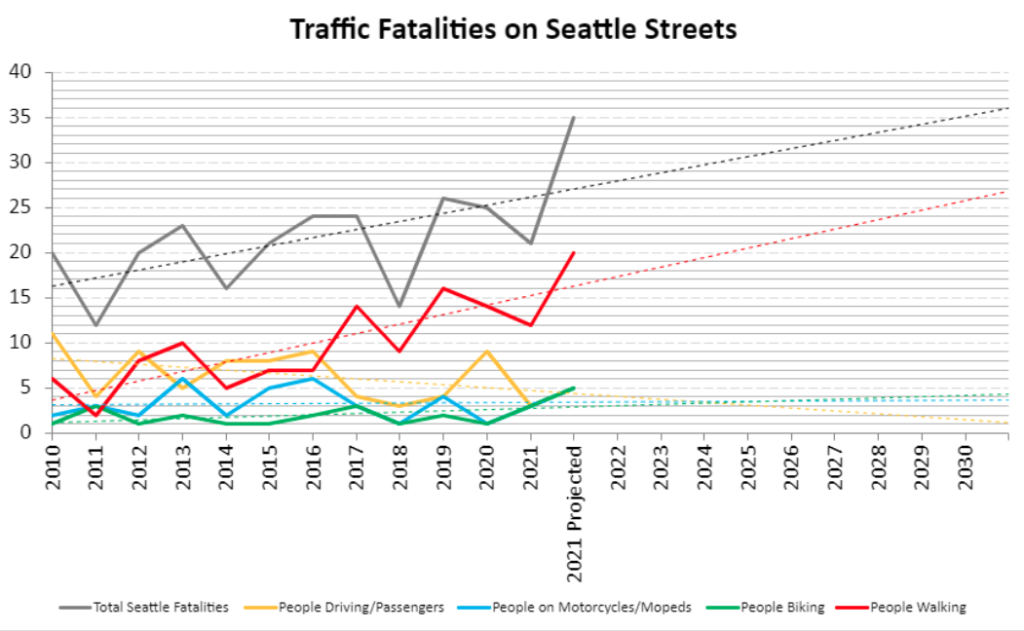

In 2015, the City of Seattle committed to a “Vision Zero” goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injury collisions by 2030, but progress on that goal has been slow and intermittent. Road deaths, and especially pedestrian deaths, have been trending up in recent years rather than pointing toward zero.

The KIRO 7 story quoted pedestrian activist Doug MacDonald who called for a watchdog investigation of the scootershare program and blamed them for the safety crisis. “We have a Vision Zero crisis because scooters are not safe on these roads,” MacDonald told KIRO. Turning blame toward scooters overlooks the fact that even in the scooter fatality recorded in Seattle, a motorist running over that scooter-rider was the cause of death. Overlooking car dependence is a hazard of the trade for MacDonald.

From 2001 to 2007, MacDonald served as secretary of the Washington State Department of Transportation, where he possessed the power to implement evidence-based traffic safety interventions across the state, but he mostly whiffed on that front, preferring to fight for highway expansions, such as the Alaskan Way Viaduct replacement project.

Taming cars

One concerning scooter survey aside, the key moving part in Seattle and the State’s Vision Zero aspirations is the car. Nearly every road fatality in the state involves a car to add enough speed and mass into the equation to prove deadly. For years, transportation secretaries like MacDonald backed by transportation chairs and state legislatures have prioritizes the free and speedy movement of private automobiles. Safety was long viewed through the lens of education and enforcement rather than fundamentally redesigning urban streets to be slower and safer, as many European and Asian countries have demonstrated absolutely works.

Rather than getting carried away with scooter scare tactics, like former Mayor Jenny Durkan did, any serious safety effort would be wise to focus most attention where it deserves to be: on designing safer streets, safer cars, safer motorist behavior, and fewer people driving two-ton vehicles in the first place. Everything else nibbles around the edges.

The Urbanist has covered what a real strategy to address the pedestrian safety crisis and get on course toward eliminating traffic deaths would look like, and sadly the U.S. appears headed in the wrong direction. Rather than requiring (or at least incentivizing) lighter-weight cars with lower front-ends and banning bull bars and other dangerous accessories, regulatory authorities have stood idly by while the American car fleet continues to grow heavier and larger than ever in our history. This trend toward heavier cars has also erased vehicle efficiency gains, boosting climate emissions. Studies have tied bigger cars to higher injury and death rates in collisions, particularly with pedestrians, but officials still do next to nothing. Rather than pouring investment into rapid transit, protected bike lanes, sidewalks, and pedestrianizing streets, highways continue to eat first when it comes to federal and state infrastructure spending. Plowing more highways through urban neighborhoods is still in the playbook.

Instead of a come to Jesus moment on Vision Zero or climate action, Seattle appears poised to wage a drawn-out debate over e-scooters right after cars killed 31 people in one year, most of them pedestrians, a 15-year high. Let’s implement SDOT’s commonsense scootershare improvements and move on to more pressing policy challenges more worthy of the hoopla and handwringing.

The full scootershare survey results are available here.

Update: SDOT announced on May 12th that its was approving permits for Bird, Lime, Veo, and LINK and parting ways with Wheels and Spin based on how the companies scored on its application.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.