Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell voted against taking fare violations out of the court system, blocking that amendment, and against taking fines out of collections, which passed 13-3 without him.

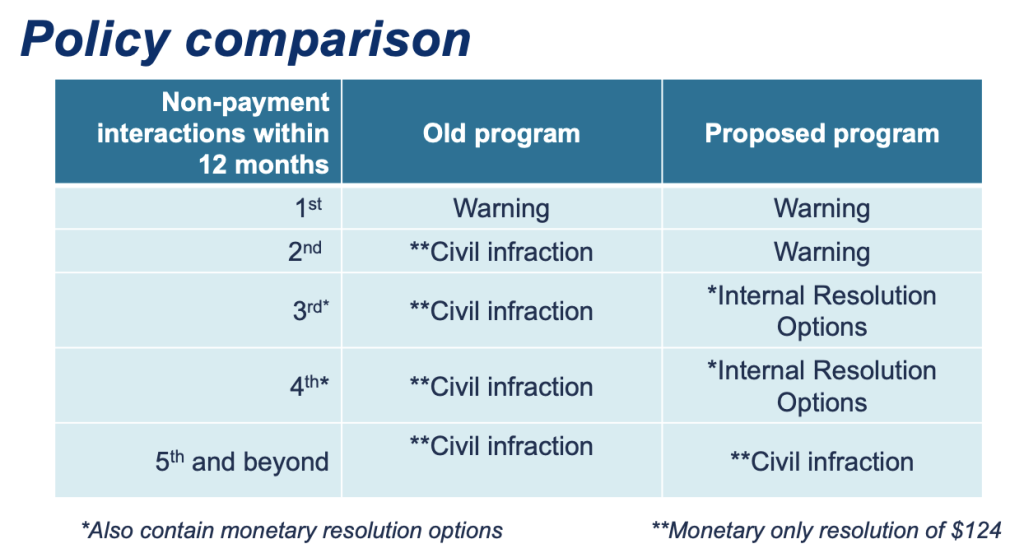

Yesterday, the Sound Transit Board of Directors unanimously passed a much anticipated fare reform package that is aimed at reducing the racially disproportionate impact of fare enforcement and the criminalization of poverty. The new system would require five violations in a 12-month period in order to become a civil infraction in the court system, increasing from just two times under the old system. Additionally, fines will drop from $124 after two warnings to $50 for the third violation, $75 for the fourth violation, and $124 for the fifth violation and subsequent infractions in a 12-month period. The reform will go into effect in the fall.

Sound Transit follows in the footsteps of King County Metro, which implemented a pilot program in 2018 and enacted permanent fare reform shortly thereafter, albeit belatedly and with less sweeping changes. Both agency’s data has consistently demonstrated disparate racial impacts. Writing in The Urbanist in January, Guy Oron noted that a persistent pattern of Black riders facing far worse outcomes, suggesting the fare enforcement system was racially biased.

“Between 2009 and 2019, Sound Transit issued nearly 38,000 citations and over 3,000 theft charges to Sounder and Link light rail riders who failed to pay fares,” Oron wrote. “Black passengers received 46.7% of citations and 56.9% of theft charges, compared to White passengers who received 34.5% of citations and 26.9% of theft charges.” The population of the Seattle metropolitan region is 7% Black.

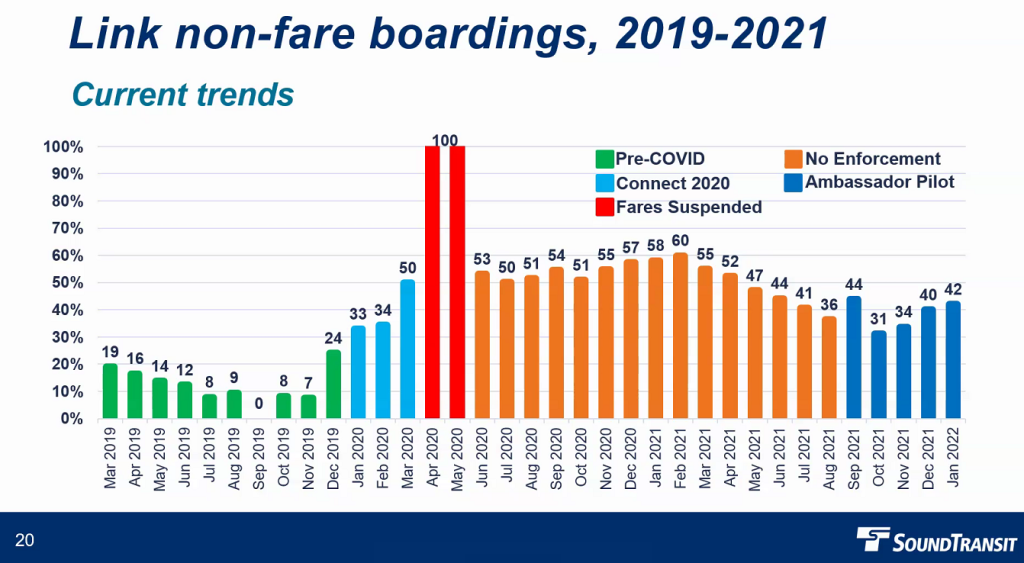

Debate was all over the map with some boardmembers insisting stiff penalties were essential to drive up fare compliance (and thus fare revenue), maintain order, and even prevent the “breakdown of civil society,” as King County Councilmember Dave Upthegrove put it. Several members, like Lynnwood Mayor Christine Frizzell, warned many riders would take advantage of the increased use of warnings rather than citations that the new system will offer and stop paying, free of the imminent threat of fines and court appearances.

Sound Transit CEO Peter Rogoff has repeatedly expressed concern about waning fare revenue and linked it to high rates fare evasion. However, the agency has not yet been able to quantify the cost of fare evasion in concrete terms, King County Council President Claudia Balducci said, and most of the lost fare revenue is due to cratering ridership and reduced service levels during the pandemic. Link ridership is at 82% of pre-pandemic level (albeit buoyed by the opening of Northgate Link light rail extension in October 2021) but the agency’s Sounder train and express bus ridership are still way down. Some transit advocates, including Seattle Transit Riders Union, have called for phasing out fares altogether.

The board is composed of mayors, councilmembers, and county executives from across the three-county Sound Transit taxing district. Representatives from Snohomish and Pierce County expressed the most reluctance to ease fare nonpayment penalties, but Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell shared their concerns, breaking from most of the King County delegation on two key amendments.

Both decriminalization amendments came from King County Councilmember Joe McDermott. The first amendment sought to take all fare infractions out of the court system, instead keeping them internal with the agency like the third and fourth infractions in the new system. Entangling low-income riders in the courts was likely to lock them in a cycle of poverty, proponents argued. Opponents rested on tradition and argued fare compliance and rule of law would suffer. That amendment failed on a narrow 7-9 vote, with both Harrell and Seattle City Council President Debora Juarez voting against the amendment — bucking most of the rest of the King County delegation.

McDermott’s second amendment sought to take fare infractions out of collection services. Juarez backed this amendment, arguing that lessening the hit to the credit scores of low-income riders was essential since the credit system is already so racist in impact, likening it to redlining. Harrell disagreed with his ally on council, arguing that the agency couldn’t fully control what courts do and that the amendment overpromised on what it could deliver. He argued the agency’s proposal was good enough and said he trusted their racial equity work. The amendment passed 13 to 3, with Harrell joining Pierce County Executive Bruce Dammeier and Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers in opposition.

Once cases end up in collections, the racial disparity also present in citation data continues, and, even when resolved, the revenue does not end up in Sound Transit coffers, instead bankrolling the private fare collection agencies to continue hounding low-income riders.

“A survey of over 7,000 citations in King County District Court from public records obtained in late August 2019 showed that over 5,000 of the citations remained unresolved, with Black passengers more likely to have unresolved tickets than resolved ones,” Oron wrote in January. “Unpaid court debt is often handed over to fare collection services, which charge extortionate interest rates and may use underhanded tactics to extract revenue.”

Next up, board members entertained an amendment from Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin allowing Sound to charge a $124 fine on the fourth infraction if the rider does not resolve their third infraction, either by paying the $50 fine or by signing up for ORCA Lift reduced fare program. Her amendment also would have sped up the process of sending fines into collections, except that this was invalidated by the previous amendment. She argued only 1 in 24 rides results in a fare check interaction according to agency estimates, so they should ramp up penalties to compensate. The Franklin amendment failed on a 6-to-11 vote, with Harrell joining the reformers in voting no on this one.

Keel had an amendment directing fare enforcement to ask riders to provide personal identification in order to confirm their identity for a fare infraction. Sound Transit claimed 76% of riders refused to identify themselves to fare enforcement officers during the study period, and Keel worried they’d give “Joe Blow” or some other alias. Harrell opposed this amendment, arguing it infringed on privacy rights and could intimidate undocumented immigrants. Nonetheless, Keel’s amendment passed 11 to 6.

In comments before the final vote, Upthegrove provided an impassioned speech arguing fare enforcement was essential to ensure the rule of law and health of civil society. He contended fare violators come in three categories: those that can’t pay due to poverty, those that honestly forgot, and “cheating assholes” that flaunt the rules on purposes. Though he supported McDermott’s amendments, Upthegrove argued it was essential they punish those willful fare cheaters. He also contemplated adding turnstiles at stations if fare enforcement agents can’t get the job done.

The board preceded to pass the policy reforms unanimously.

The Sound Transit Board of Directors punted on decisions about the agency’s fare ambassador program, with the meeting dragging toward four hours and members late for other appointments. The fare reform package directs law enforcement to not involve itself in fare enforcement. So the fare ambassadors will be the stewards of the reform and a future vote will clarify their role.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.