The Housing Development Consortium (HDC), a prominent player in affordable housing creation in the Seattle region, has come out against proposed ballot Initiative 135, which seeks to create a public development authority to build and maintain social housing in Seattle. In a statement published on April 27th on its website, HDC cites concerns that Initiative 135 would “[distract] funds and energy away from what our community should be focusing on – scaling up affordable housing for low-income people.”

“We do not need another government entity to build housing when there are already insufficient resources to fund existing entities,” HDC wrote, addressing its member organizations.

Initiative 135 was filed by the House Our Neighbors (HON) coalition, which initially formed in opposition to the proposed “Compassion Seattle” city charter amendment in 2021. As The Urbanist outlined in a previous article and podcast episode, according to the language of initiative, the social housing created by the new public developer would be available for both low and moderate income households, utilizing a different model than current affordable housing efforts in the region.

“We see Initiative 135, and the public developer it would create, as an opportunity to build out a deeply affordable housing mechanism that is not commodifiable; ensures that anyone earning between 0-120% area median income (AMI) have access to quality, permanently affordable housing; ensures that renters finally have voice in the housing they live in; and is not restricted by federal financing mechanisms,” Tiffani McCoy said in an email.

HON supporters expressed frustration on social media that HDC was opposing their social housing effort. Among them was former Seattle Mayor candidate Cary Moon, whom The Urbanist Elections Committee endorsed in her 2017 run against Jenny Durkan.

“This is bad politics and short sighted, HDC! You and your members do good work at huge effort. But we all know: we are not building anywhere near enough affordable housing,” Moon said in a tweet. “The initiative tasks City Council with establishing a viable new funding source. That is good AND NECESSARY. Please don’t claim you’re for innovation but then block a grassroots effort to identify new funding and better process to build permanently affordable social housing. This initiative is our chance to figure it out together.”

HDC, however, is concerned about the potential consequences of diverting any affordable housing funds away from the creation of homes for low-income households, especially those who are members of vulnerable Black, Indigenous, and people of color communities (BIPOC).

While the statement does not reflect the viewpoints of individual member organizations, those member organizations include leading affordable housing providers like the Seattle Housing Authority, Chief Seattle Club, Africatown Community Land Trust, Downtown Emergency Service Center (DESC), Community Roots Housing, Catholic Housing Services, El Centro de la Raza, the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI), and the Refugee Women’s Alliance (ReWA). HDC members also include consultants, architects, building contractors, attorneys, accountants, government agencies, and financial institutions, such as Capitol One, US Bank, Umpqua Bank, BECU, Microsoft, and more.

“In launching the campaign, the organizers have undermined the legitimacy of existing public and non-profit organizations that are already engaged in this vital affordable housing work,” the statement reads. “We are concerned that the initiative distracts our community from investing in and supporting existing community-based nonprofits, based in cultural communities, that need continued energy and investment to thrive as housing developers, owners, and operators.”

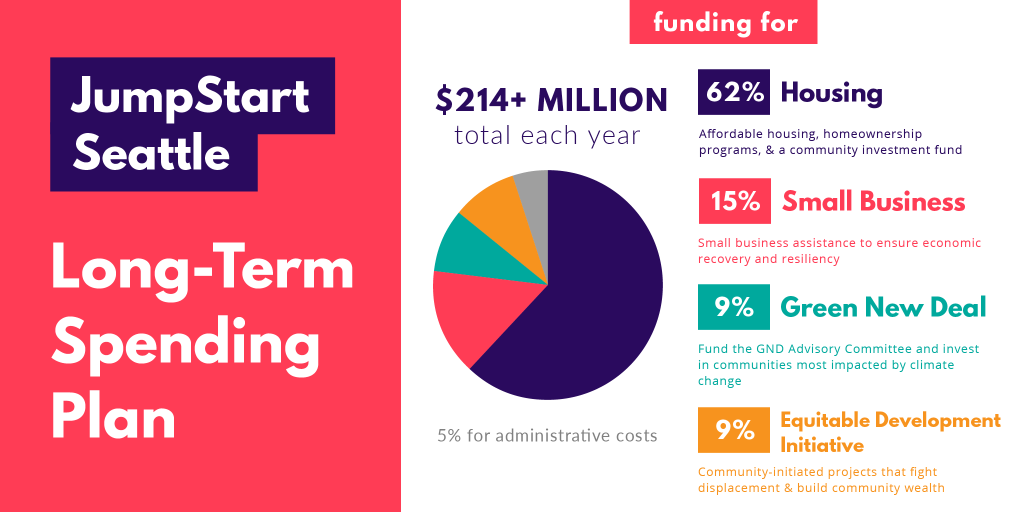

At least one HDC member organization did not agree with that assessment. Seattle-based developer Ben Maritz, founder of Great Expectations, LLC, argued the city should innovate and try new ways to invests its greater resources via new sources like the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) inclusionary zoning program and JumpStart Seattle progressive payroll tax, which is projected to provide about $235 million annually, with 62% set aside for housing creation.

“HDC coming out against #socialhousing is sort of weird and ignores the fact that affordable housing funding has pretty much tripled in the past two years (with the addition of MHA and JumpStart),” Maritz said in a tweet. “We should absolutely be using that funding to innovate.”

Maritz argued that the traditional nonprofit model of braiding together City and philanthropic funds with Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) from the federal government has major limitations and wouldn’t be up to task of solving the housing affordability crisis. The LIHTC program works by providing corporations and financial institutions tax breaks in exchange for funding affordable housing. When corporate tax liabilities go down — such as following the Trump tax cuts — so too does the supply of LIHTC.

“The existing model of using city funds to plug holes in LIHTC capital stacks assumes an infinite supply of LIHTC, which doesn’t exist. It also is a costly and slow way to build housing,” Martiz added.

HDC, however, stressed the lack of funding source baked into Initiative 135 as a drawback. Backers have said that they intend for the funding source to be progressive, but have not as yet identified exactly where it come from — instead instructing the Seattle City Council to establish a new funding source. While eventually the goal for the public developer is to issue bonds against projected rental income that serve as a significant source for funding both the creation of housing and ongoing operations, funding to kickstart the effort would be necessary.

“…[T]he funds necessary to set up the additional citywide PDA (public development authority) would likely draw from existing affordable housing funding that could otherwise be dedicated to creating homes for our lowest-income neighbors,” HDC writes.

HDC’s statement did not address the process for public lands that would be established under Initiative 135. Written into the language of the ballot initiative is the requirement of a city feasibility study to determine housing need and whether the land should be transferred to the developer before considering the sale of said land.”

According to the City of Seattle, currently most surplus public land is sold to the highest bidder; however, a state level bill passed in 2018 (SB 2382) “grants authority to cities to sell surplus property for below fair-market value – all the way to $0 – as long as the land is used for permanently affordable housing.”

In the current system, any developer of permanently affordable housing could be in the running for these surplus city lands; however, if Initiative 135 passes, first consideration would go to the new public developer. While there would be no prohibition against selling the land to another affordable housing developer — especially if there were a vested interest in creating land for a specific population such as people exiting homelessness, the fact that the land would pass through this process could be of concern to other developers of affordable housing in Seattle.

For HON the desire to test out a new model of affordable housing creation in Seattle, goes beyond the goal of creating mixed-income communities.

“Social housing is a tool that works across the globe, why shouldn’t we utilize it here to address our deep affordability crisis? Why can’t renters have a say in their living conditions? Why shouldn’t we fight for more progressive revenue to fund deeply affordable housing?” McCoy asked. “Why can’t we have high quality housing, with passivhaus standards, that is community controlled? Why do we have to accept this system that isn’t building to scale what we need?”

Both the increased level of community governance and the environmental standards set by Initiative 135 further differentiate it from current models. Instead of addressing those goals, HDC’s statement focuses its messaging on how the initiative may impact the already tight funding landscape for affordable housing.

“We welcome innovation and share many of the same values as the backers of the Initiative. These include the belief that every person deserves a safe, affordable home, and that we need a scale of public investment in affordable housing that lives up to this value,” the statement reads. “However, this Initiative would divert scarce public resources toward the creation of a new bureaucracy and is a distraction from what should be our priority as a City—greatly increasing funding for affordable housing to meet the scale of the need.”

In their statement, HDC also referenced the need to stand strong in support of the next Seattle Housing Levy, which will come before voters for approval in 2023, and alludes to a risk Initiative 135 could pose to levy renewal. The previous levy, which raised $290 million over seven years, was passed in 2016 with 71% approval. Given these strong numbers, and the continuing nature of the city’s housing affordability woes, it appears unlikely that the levy is in jeopardy. In an email, HDC Executive Director Patience Malaba said the coalition had not yet conducted polling. However, HDC’s statement underscores the levy’s importance as a tool with “a proven record of contributing funds to affordable housing developments that bring people inside and keep them in their communities.”

HON is still gathering signatures for Initiative 135 so it is not known yet if it will appear on the November ballot. HDC presenting opposition is notable, but not completely unforeseen given the tight nature of funding available for affordable housing in Seattle. At this point, the divergence between these two parties seems to rest on a central point: should affordable housing funding be pumped into the existing model prioritizing low-income households? Or should Seattle explore a new social housing model that creates mixed-income housing for both low-income and moderate-income households using cross subsidy to help pay for it and aiming to meet higher environmental, sociological, and community governance standards? In the upcoming months, it will be up to Seattleites to answer this question.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.