Sound Transit plans to open Lynnwood Link in 2024, but the Lynnwood City Council is already signaling some hesitancy about transit-oriented development near the city’s light rail station, potentially hampering long-laid plans.

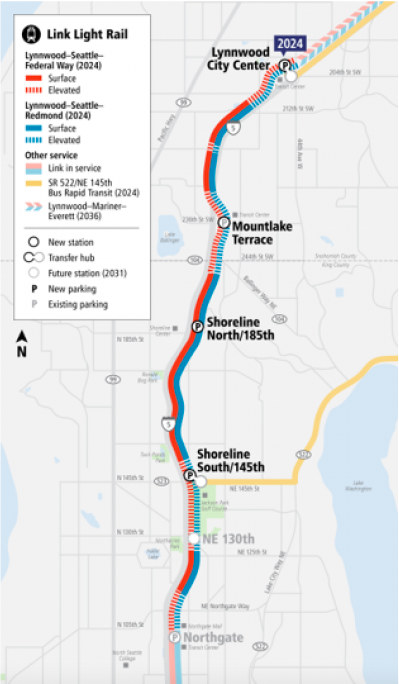

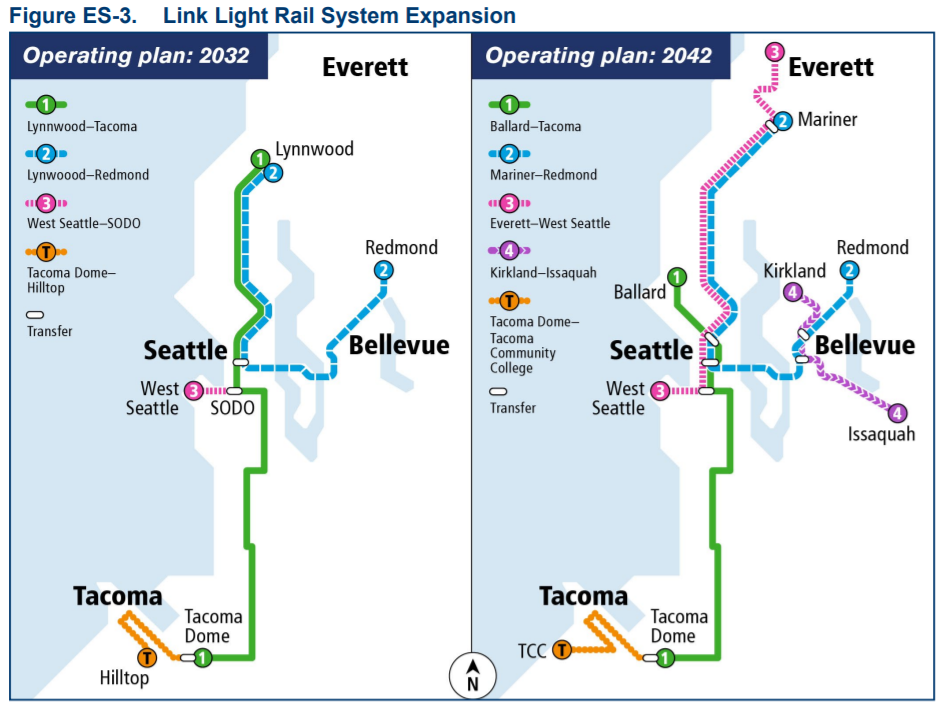

The northern terminus of both the Link 1 Line to Federal Way and the 2 Line to Redmond will be Lynnwood City Center Station — Line 1 will then extend to Everett around 2037. Lynnwood will also be the northern terminus of Sound Transit’s I-405 Stride “S2” bus rapid transit line to Bellevue, currently scheduled to open in 2027, as well as the forthcoming Community Transit Swift Orange line connecting Edmonds and Mill Creek in 2024. Lynnwood is heading toward being one of the most transit-connected cities in the entire region, a position many cities would clamor to be in.

But after the turnover of three city council seats in 2021 potentially bolstering a bloc of growth skeptics already on council, there are signs that the new Lynnwood City Council is not as interested in accommodating new residents to the city near frequent transit. A shift in an approach to housing at such a key transit node could have broader implications and lead the entire central Puget Sound away from accommodating planned growth.

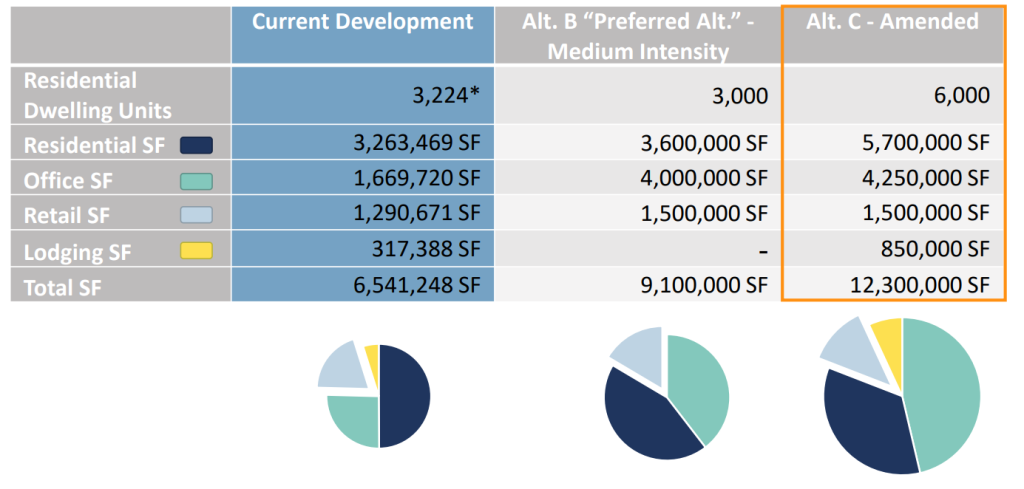

At the center of this fight is the City Center neighborhood, directly next to the soon-to-open light rail station, where development has been very robust, in part because of prior actions by the City of Lynnwood to intentionally focus growth in the area. In 2012, Lynnwood adopted an ordinance that adopted a streamlined process for new residential and office development within the city center neighborhood: individual projects did not need to conduct their own separate full environmental review under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA), which also reduces opportunities for housing appeals that delay projects. But that ordinance topped out at 3,000 new residential units — which the neighborhood has now exceeded, with 3,224 units already created or in the development pipeline, according to city staff.

Now Lynnwood’s planning commission has unanimously recommended that the city council adopt a new ordinance that increases the number of residential units that would be pre-cleared from 3,000 to 6,000, as well as modestly increasing the amount of square footage of office space and adding new hotels into the mix. “The proposed update will support the continued momentum of the City Center Vision as a gathering place for future employment and housing. This includes private investment continuing to be a catalyst for placemaking within the emerging neighborhood,” the staff report to council noted.

It’s important to note that no major zoning changes are being proposed here, and without adopting this change new housing would continue to be built in City Center, it will just happen more slowly, and other areas of the region (including ones with fewer transit options) may become more attractive to housing developers. But at a public hearing on the proposal on Monday, a sizable bloc of the Lynnwood City Council expressed their concerns about approving such an ordinance, several doing so in ways that suggested they might not be fully aware of what the process entails. Just last year, Lynnwood adopted a Housing Action Plan that included among its top strategies a proposal to continue to promote housing in the Regional Growth Centers (which include both the Alderwood mall area and City Center) and along major transportation corridors.

Video from April 25 Lynnwood City Council meeting. (City of Lynnwood)

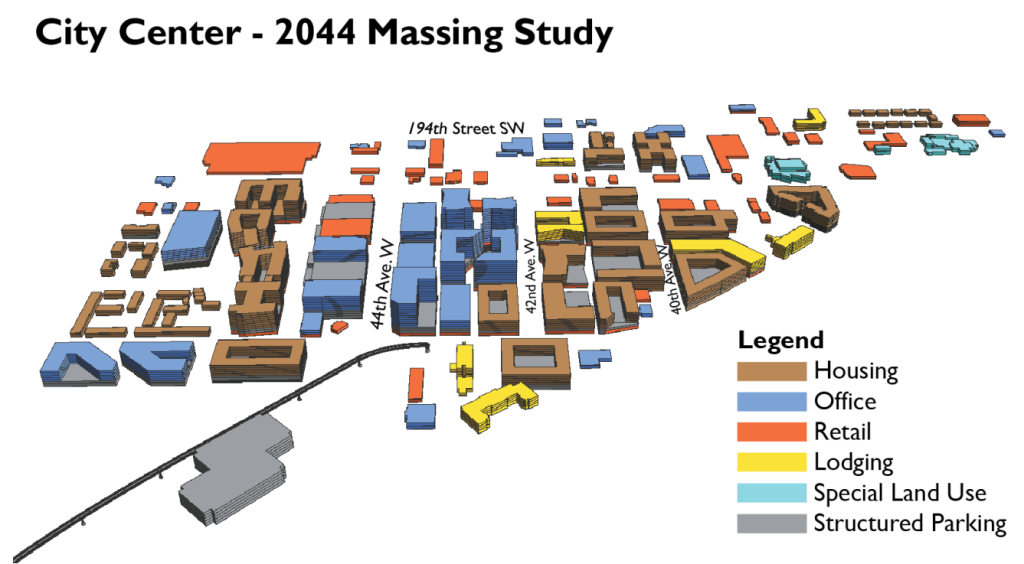

During the meeting, city staff presented a visualization of what the City Center neighborhood could look like if all of the development capacity was utilized over the next two decades — not intended to be an exact prediction but rather just to provide a sense of how built-out the neighborhood could be. The illustration doesn’t depict a skyscraper village but rather a broad array of midrise mixed use buildings. Several councilmembers were very concerned about what the proposal could do to Lynnwood.

“Too much housing” is how Councilmember Shannon Sessions described the proposal to allow streamlined development within the existing zoning in City Center.

“Adding another 3,000 units [under current law] is going to be plenty, and it’s even more than I want to have there, but 6,000… I can’t go along with that at all,” added Councilmember Jim Smith, who lost an election to become Lynnwood’s mayor last year. Smith suggested that new residents in City Center were somehow separate from a majority of Lynnwood residents. “Going from 3,000 to 6,000 does nothing — absolutely nothing — for the people of Lynnwood,” he said. “This will increase traffic, this will increase crime — and I know I’m not an expert in those areas, but it’s kind of common sense that we know this stuff.”

Smith and Sessions were joined by Councilmember Patrick Decker, who was elected last year and serves as the liaison to the Lynnwood Planning Commission. Decker noted that he thought 3,000 residential units in City Center was enough.

“There’s no mandate that Lynnwood has to accommodate every person that wants to move to the Pacific Northwest. There are a lot of cities in the area, there’s a lot of other areas for growth… there’s a lot of area up north where people can live. It’s our job to protect the residents of this city and ensure they’re properly cared for,” Decker said. “I’m in favor of planned growth, I’m not in favor of forced growth. To me, they are two completely separate things,” he said, suggesting that the city could withstand having grants withheld if the city fell out of compliance with its housing production goals in compliance with the Growth Management Act.

Pushing back on those voices on the council was Councilmember Josh Binda. “I feel like this kind of growth in Lynnwood is inevitable,” Binda said, asking his colleagues if they’d prefer to have to be reactive to increases in housing production or get out ahead of that development as this proposed ordinance attempts to do. Elected in 2021 as a 21-year-old, Binda is Lynnwood youngest councilmember, and he’s also one of its two Black members, along with Sutton.

Council President George Hurst, who seemed to support the proposed ordinance as well, emphasized the long-term nature of the change, which is intended to extend to 2044. “The overriding thing for me is that the city of Lynnwood residents, that keep being referenced to, have long asked for a city center, something that can be focused, that people can come to.”

Hurst also warned blocking change and growth would be impossible.

“We may not like this change… but it is a changing city, and I think we have forward-enough thinking councilmembers that we can address these changes,” he said. “We’re not going to be able to stop the growth, we’re really not.”

Other councilmembers didn’t share their thoughts on the issue of building additional units in the City Center, with Mayor Christine Frizzell included on that list. Also quiet was Councilmember Shirley Sutton, another new councilmember who took office this year. During the 2021 campaign she told Lynnwood Today that “[Lynnwood] should be open to high rises and rezoning for multiple family dwellings. With enough outdoor space, parks and ample public transit, a higher density city is livable and even desirable.”

Sutton won her seat by just 101 votes to Nick Coelho, who tweeted following this week’s council meeting that “[w]e needed real housing advocates who understand density, development, and design, and could meaningfully lead on these issues within the Council.” A 34-year-old renter, Coelho ran on allowing triplexes and corner stores in single family zones and promoting affordability and walkability, particularly in the city center.

The city council is set to vote on the proposed ordinance on May 9, but whether it has the votes to pass is unclear at this point, given the sharp criticism from three members and cageyness from others. Rejecting the path for City Center that Lynnwood has been working on for a few decades would be a clear illustration that the current city council is heading in a reactionary direction on the issue of housing.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.