Very few cities in the region will see two new Sound Transit light rail stations open within their borders by the end of this decade, and the City of Shoreline is one of them. Shoreline has done a lot to prepare for those two stations, including making way for more housing, funding new sidewalks around the stations, and assembling funding for a new pedestrian and bicycle bridge next to South Shoreline station at 148th Street. Earlier this month, the Shoreline City Council also voted to move ahead with analyzing a comprehensive plan amendment that could allow for missing middle housing like duplexes and triplexes to built across the entire 12 square mile city, approximately 70% of which is still zoned single family only.

Shoreline is also upgrading its transportation plan, with an explicit goal of making it easier for people to get around the city without a private vehicle. Included in that update are a number of reforms intended to move Shoreline away from its current car-oriented development patterns, although some of the proposed reforms might not go far enough to achieve its vision.

Steps toward prioritizing people ahead of vehicles along key corridors

Like many cities, Shoreline currently utilizes a “level of service” standard for moving cars and trucks through its arterial street network and gauging where additional roadway capacity is needed. The level of service, measured on a scale from A to F, measures how long an individual vehicle would be delayed getting through an intersection due to the presence of other vehicles.

The current status quo in Shoreline is that intersections receiving a “E” grade (more than 55 seconds of delay per vehicle), or worse, require mitigation when new development is projected to add vehicles to the street. Standards like this are a driving force behind the forthcoming expansion of NE 145th Street at I-5, where a set of planned roundabouts are about to take shape in the name of improving traffic flow.

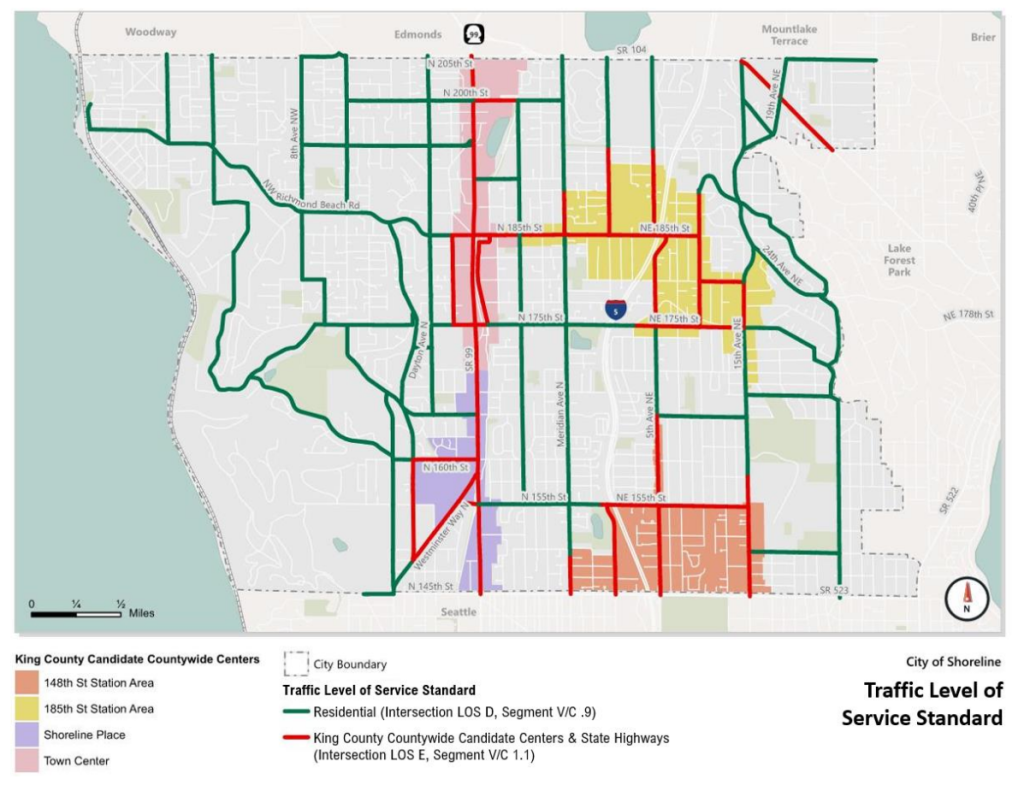

Now that the city is updating its decade-old transportation plan, staff are recommending the City Council adopt a new standard for level of service in areas where the city is focusing the most development: the station areas around the 148th and 185th Street light rail stations, and along the entirety of Aurora Ave N adjacent to the Town Center and Shoreline place urban centers. The acceptable level of service for intersections along these corridors (highlighted in red below) would drop from “D” to “E,” meaning the threshold for delay before mitigation would be required would go from 55 seconds to 80 seconds.

This approach leaves the status quo in place in the rest of Shoreline, which the City says will uphold a beneficial policy that maintains “a more appropriate delay standard in locations with less supportive transportation infrastructure (e.g. small pockets of commercial land use).”

On the other hand, cities like Seattle have departed from the traditional level of service determination entirely, instead moving toward measuring the desired percentage of residents traveling by a certain mode in different areas depending on the level of infrastructure. This approach moves the city away from level of service requirements that necessitate the addition of car infrastructure in the exact places where other modes of transportation should be prioritized.

Shoreline’s bike plan gets a revamp

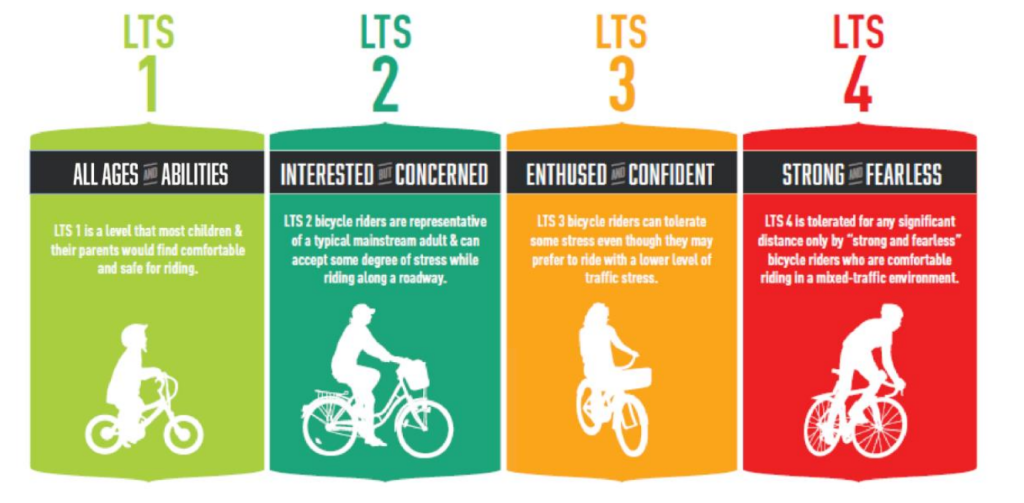

At the same time it is rethinking level-of-service considerations in important urban centers, Shoreline is also updating its citywide bicycle plan. Where the vehicle network is guided by level of service, the bike plan would be guided by “level of traffic stress” (LTS), a way of measuring roads where people on bikes feel comfortable.

Facilities with a designated as LTS 1 are accessible to users of all ages and abilities, while those at LTS 4 are only for the most hardened cyclist who are comforting navigating the road like a vehicle at all times.

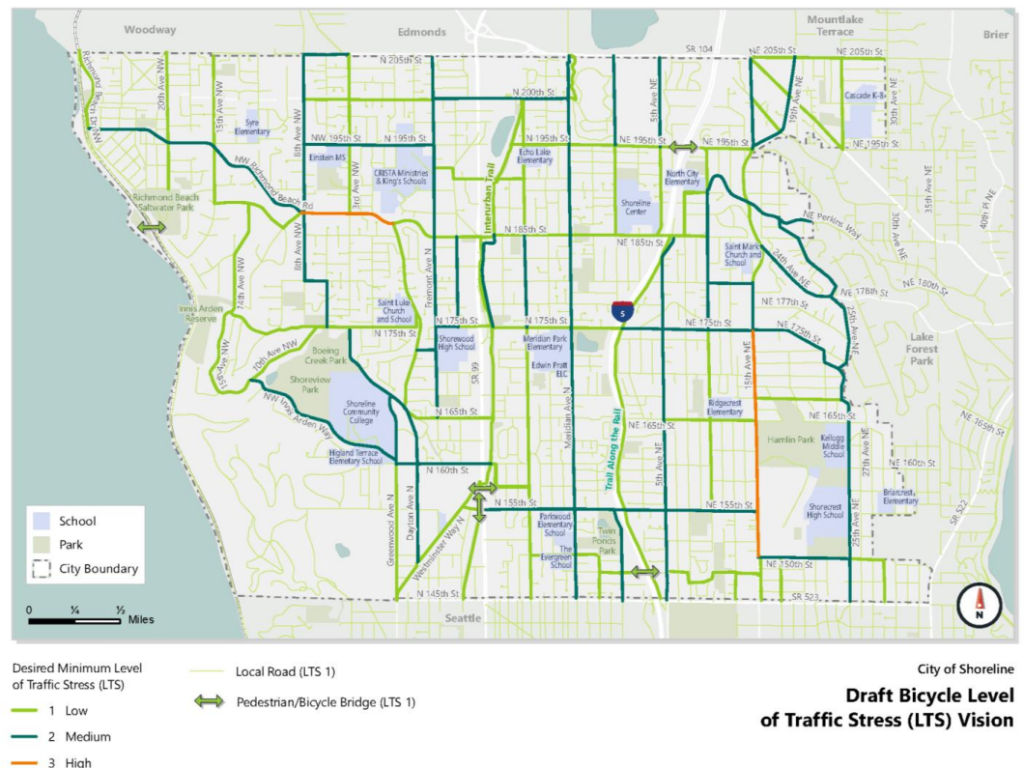

But while many arterial streets in Shoreline would be designated as having a goal of seeing all ages and abilities infrastructure, many connections would get designated as LTS 2 instead, and a few key connections would even be rated as being reserved for enthused and confident riders only (LTS 3). One of these is Richmond Beach Road, one of only a few east-west arterials that connect across the north end of Shoreline to the light rail station at 185th Street. The other is 15th Avenue NE, a connection to businesses on the east side of I-5.

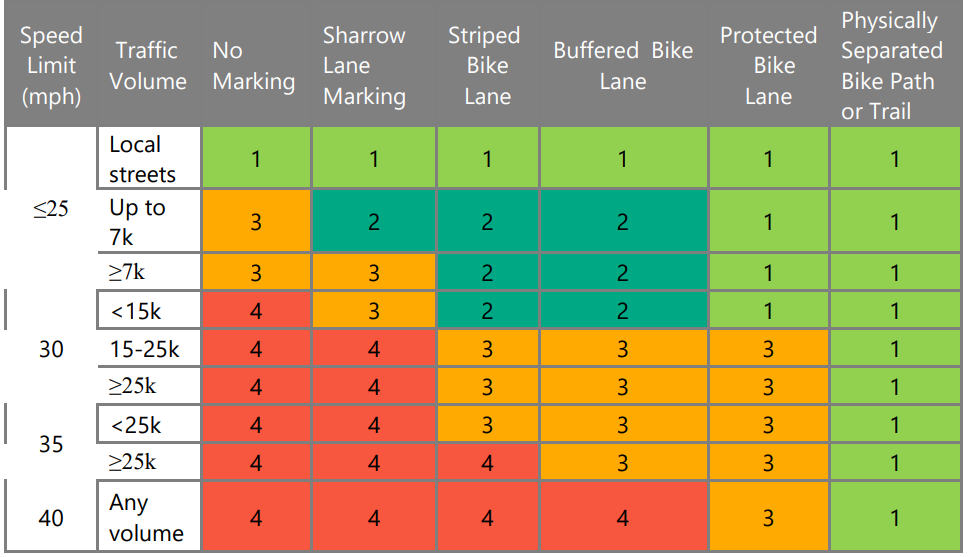

If that framework is approved, the type of bike facility installed would align with that desired level of service level combined with the road’s speed limit and traffic volume. Shoreline’s proposed metrics (illustrated in the chart below) are heavily tilted toward physically separated trails, which in many cases would translate to a wider sidewalk for riders to use, as the city is currently proposing along most of the 175th Street corridor.

A protected bike lane on a street with over 15,000 daily vehicles would actually be ruled too stressful under this rubric to qualify as accommodating riders of all ages and abilities. Meanwhile, arterial streets with relatively lower volumes (up to 7,000 vehicles per day) could see sharrows, arrows that indicate that bicycles share the road with cars, which aren’t bike infrastructure at all.

During a City Council meeting last week on the plan, Councilmember Christopher Roberts noted that streets around the forthcoming light rail stations could see increased traffic volumes even as they continue to be designated as “local.”

“When we’re designing and looking at these streets, we have to recognize there is variability there,” he said.

Roberts also pushed to eliminate some of the less protected facilities from the toolbox. “When we’re developing our bike network, I don’t see how striped bike lanes really work… I think that when we’re building our network and putting in new bike lanes, our minimum should be at least a buffered bike lane, but really we should be putting protected bike lanes wherever we can, and not just put paint on the ground and call it a bike lane.”

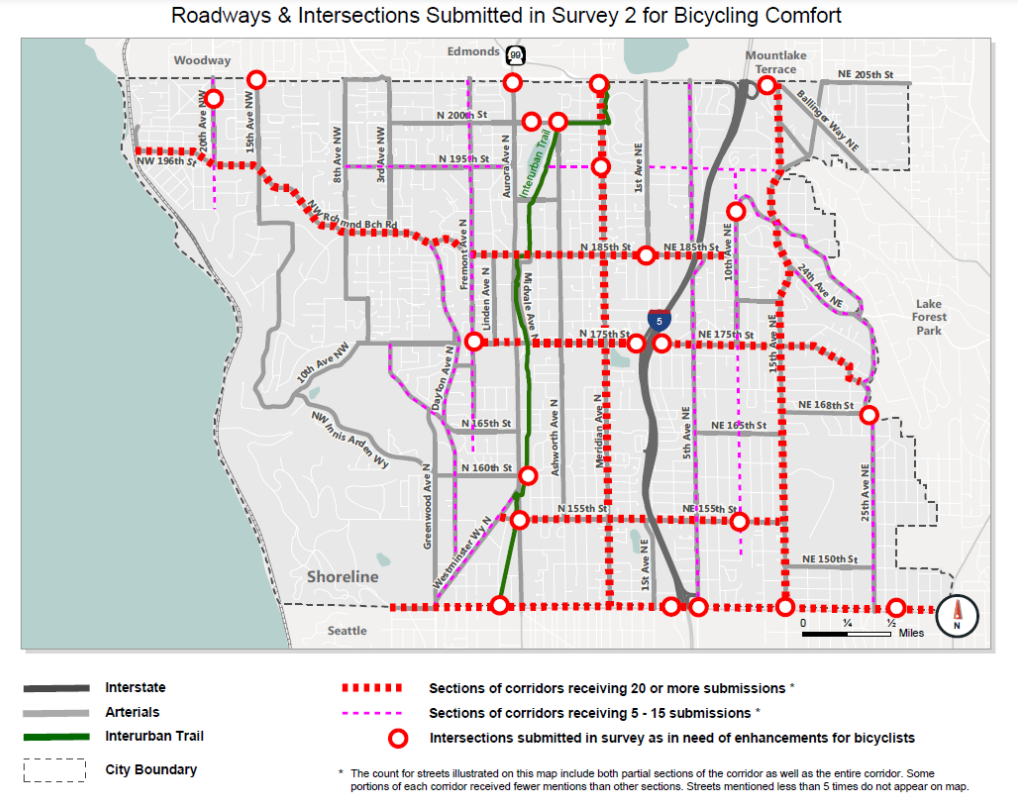

During the outreach process for the bicycle plan update, Shoreline asked members of the public to indicate where they would like to see bike safety improvements made. The 145th Street corridor, where the city is widening the street, but moving people on bikes onto a circuitous “off-corridor” bike network, was rated very highly by respondents for bicycling comfort; the question is what the City can do to get the other corridors on the map right.

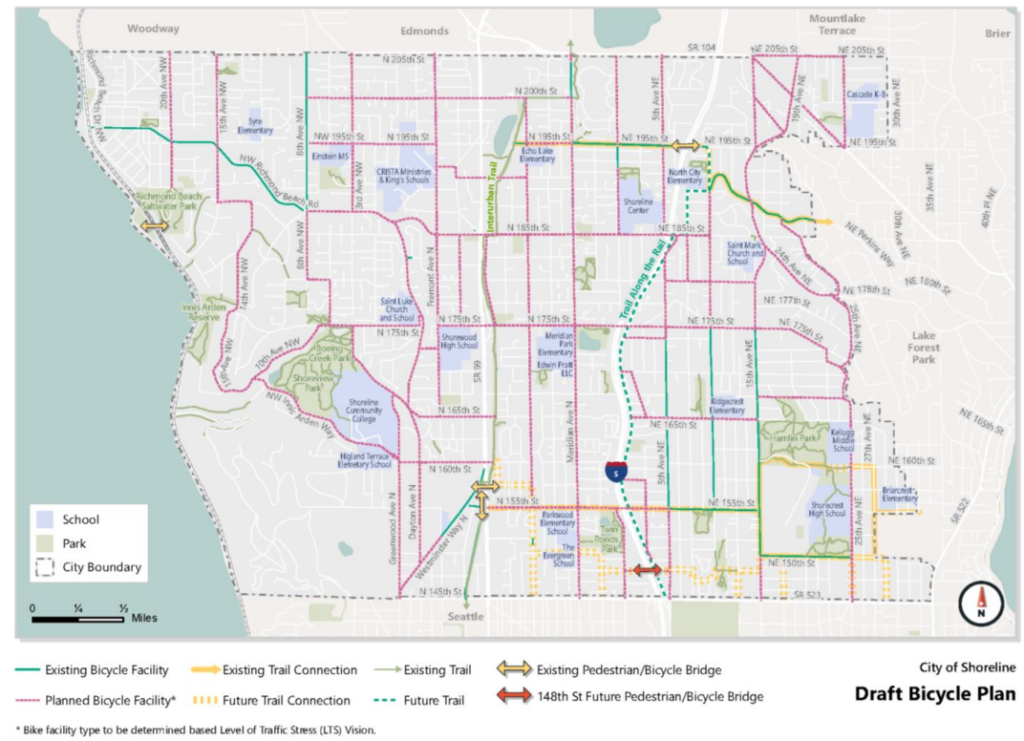

So far the City has released a draft version of the proposed citywide bike network map, shown below. In the next few months, Shoreline will be developing a specific project list that would fill in some of the gaps on the map and then adopt that list as part of the full transportation master plan. It remains to be seen if the Shoreline City Council can be as bold in creating a safe bike network as they have been in pushing for changes to increase the supply of housing.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.