Just before midnight on February 28, Cholly Elopre, a 61-year-old airport worker living in Federal Way, was crossing six lane International Boulevard in SeaTac at S 212th Street, adjacent to the Radisson Hotel. While crossing east in the crosswalk, she was struck by someone behind the wheel of an SUV and thrown 100 feet. She did not survive, and the driver of the vehicle was never located.

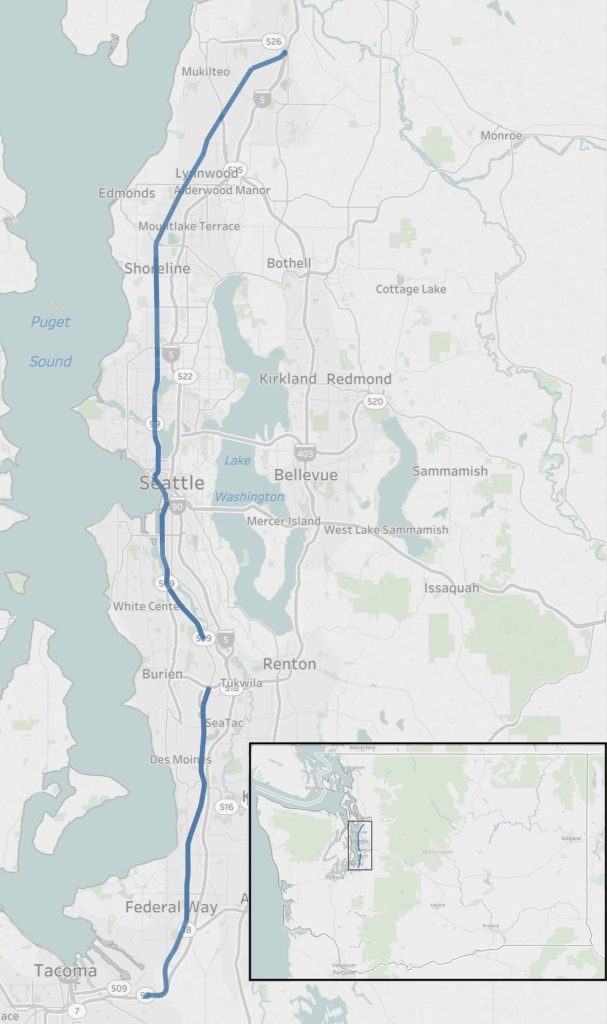

International Boulevard in SeaTac makes up a segment of SR 99, a state highway under the jurisdiction of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) that also includes East Marginal Way and Aurora Avenue in Seattle, and Pacific Highway in Snohomish County. The corridor is one of the most deadly roadways in the state: in 2021, there were 15 fatal collisions along the corridor, with 11 of those collisions involving people who weren’t in vehicles.

Six of those fatal collisions happened in south King County. As the city of Seattle begins design work on substantive changes to Aurora Avenue N in order to fix some of the most dangerous stretches of Highway 99 inside the city, with those improvements set to be funded via a $50 million appropriation from the state legislature, south King County’s segment of 99 is not receiving as much attention. But several cities along the corridor are utilizing traffic safety funds aimed at improving conditions for people walking and biking — by funding police overtime.

Five cities in south King County — Federal Way, Kent, Des Moines, Seatac, and Tukwila — are utilizing a grant from the Washington Traffic Safety Commission to deploy additional uniformed police officers along the portions of SR 99 that pass through their jurisdictions. The total grant, for the relatively modest amount of $25,200, is being split equally among the five cities. The increased patrols started two weeks ago and are set to be wrapped up by this week.

“The patrols will deploy uniformed officers along Highway 99 looking for driver behavior that are most dangerous for our walkers/rollers: failure to yield, distraction, speed, impairment, etc.,” Sara Wood, Community Education Coordinator with the Kent Police Department told me. Wood is also the “Target Zero Manager” for south King County, a position funded by a regular grant allocation from the Traffic Safety Commission, illustrating the degree to which the state’s traffic safety infrastructure is tied together with law enforcement. Wood is one of four law enforcement officers who are point persons on traffic safety solutions for entire regions in Washington State.

Wood noted that enforcement would not be focused on the behavior of pedestrians or people on bikes, but she told KUOW that “when it comes to enforcement, the officer does have some discretion” in terms of what behaviors to cite when on patrol.

In addition to overtime for patrols, grants will also be used to pay for safety education billboards along SR 99 as well as increased training for police officers in those south King County departments. But funding physical changes to the roadway is outside the scope of most Traffic Safety Commission grants, which come through the federal government and are by law required to be spent on education or enforcement activities. Even as the Federal Highway Administration has moved to embrace the Safe Systems approach, which emphasizes the fact that humans make mistakes and that the impacts of those mistakes should be mitigated, the grant funding structures have not kept up. The role of police officers pulling over drivers to enforce individual traffic laws lies at the periphery of the Safe Systems approach, if at all.

A 2020 idea book produced by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration titled “The Role of Law Enforcement In Supporting Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety” did not include any reference to increasing traffic stops, but rather included strategies like partnering with traffic engineers. “Trying to enforce safe behaviors in areas where the roadway environment discourages safe behaviors will not likely lead to successful long-term compliance and can lead to a complaining public,” it noted. “For example, roadway configurations that have more than two lanes in each direction, speeds of 30 miles per hour or higher, and/or non-high-visibility marked crosswalks have been associated with lower compliance rates with driver yielding laws.”

In Seattle, where the city is making headway on being able to make changes to SR 99, the department of transportation has paused partnerships with the Seattle Police Department, as part of re-examining the role of law enforcement in ensuring traffic safety. But so far such a re-examination hasn’t been as noticeable at the state level, with millions of dollars per year still going to local police departments and the Washington State Patrol with the goal of improving traffic safety, even as serious injuries and fatalities have continued to increase. The degree to which that starts to change will show how serious the state is about embracing true Safe Systems.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.