The Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) Transportation Policy Board, which is made up of elected officials from around the four counties of central Puget Sound, has sifted through dozens of proposed amendments to the region’s draft 2050 Regional Transportation Plan. The result is that the board has signed off on a plan that is slightly modified, but mostly unchanged, from the one members saw for the first time in early January.

In a development that’s unusual for this kind of amendment process, the board members didn’t actually vote on the actual language proposed by their fellow elected officials. Instead they voted on language interpreting those amendments that had been written by PSRC staff, and within these write-ups were many outright recommendations on proposed amendments staff members felt the board shouldn’t take action on. Additionally, other amendments were significantly modified in their written description from what had been directly proposed by elected officials.

As a result, PSRC staff had a tremendous amount of influence over how the draft 2050 Regional Transportation Plan was ultimately revised, and at the end of the board’s marathon 4-hour session this past Thursday, they voted in one fell swoop to discard a set of three proposals that staff had recommended not to advance.

In another unusual move, King County Councilmember and current PSRC President Claudia Balducci directly addressed the board during the meeting, reiterating her support for substantive amendments around climate, equity, active transportation and other topics. Some of those proposed amendments were taken up, and others were not, suggesting that additional amendments could come at the PSRC Executive Board meeting (which Balducci chairs) later this month or in May.

Let’s take a look at which amendments made it through the process and which did not.

Climate Change

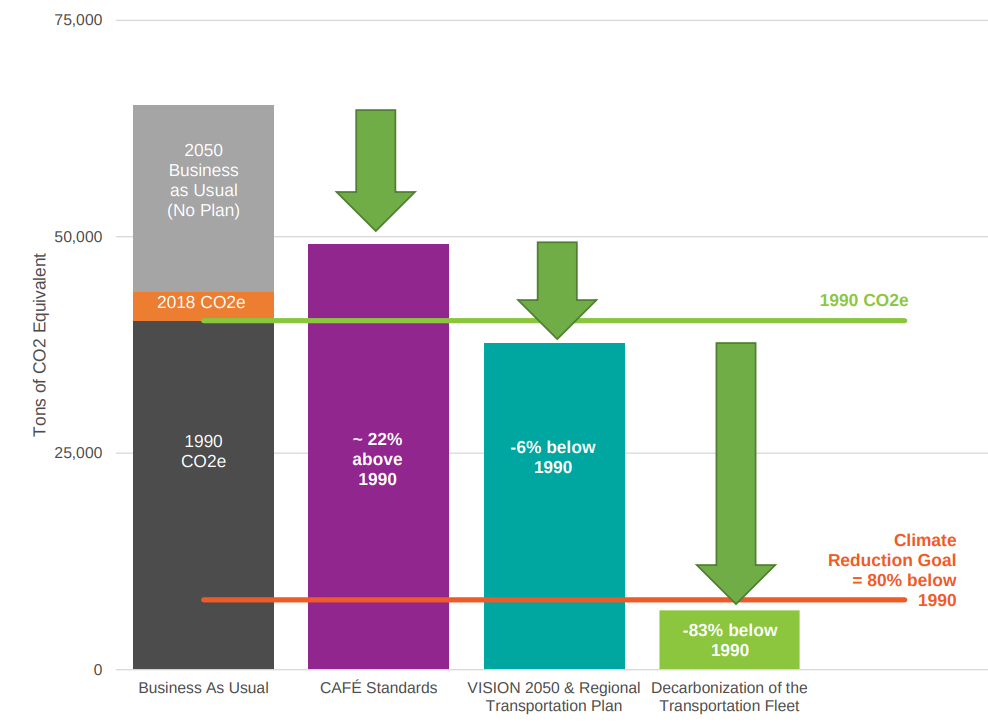

One of the most frequent topics raised in comments on the plan was the fact that PSRC doesn’t currently have emissions reductions targets for 2030, and is instead entirely focused on 2050. The assumptions around meeting that 2050 target currently depend heavily on anticipated vehicle electrification and some other policies not directly in PSRC’s control, like the implementation of a Road Usage Charge (RUC) to manage demand and reduce vehicle miles traveled.

The board unanimously approved a set of amendments that relate to that 2030 target, most of which will impact PSRC’s overall work plan more than the 2050 plan itself. The agency needs to assemble what a map of the region’s transit network will look like in eight years, recalibrate those immediate electric vehicle adoption trends, and other metrics in order to come up with that interim goal. PSRC is currently working with its partner counties to come up with an updated emissions inventory to provide a better picture of what’s actually being emitted right now, and much of this work will happen in tandem with that. What’s remarkable is that a small group of electeds are still finding it necessary to force PSRC to look more immediately in terms of emissions reduction, given the short timeline being emphasized by groups like the IPCC.

The board was not ready to adopt an amendment proposed by State Representative Emily Wicks (D-Everett) that adopts an aspirational goal for emissions reductions in every set of project grants that the Transportation Policy Board approves. PSRC oversees a substantial amount of federal grants and uses criteria, including potential for reducing GHGs, to select projects. But a majority of the board wasn’t comfortable setting a target for reductions, even one that wouldn’t be enforceable.

Hester Serebrin, who serves on the board as a member of the Washington Transportation Commission, was one of the primary voices pushing for emissions reduction targets for grant awards. “We are all committed to setting 2030 and 2050 targets… I guess I just don’t understand how we’re going to achieve that if we can’t ask, or even aspire to hit that goal or target in each of our funding rounds,” she said. “This is one of the few teeth PSRC directly controls.”

Board members who were ready to make that commitment included King County Councilmember Girmay Zahilay, Pierce County Councilmember Ryan Mello, and Seattle City Councilmember Alex Pedersen, but they were not enough to ultimately outweigh the voices of regional officials who were afraid that projects in their own cities might be impacted by funding changes.

The board did adopt an amendment that commits the agency to analyze climate resilience and environmental impacts in underrepresented communities, and to strongly consider hiring a dedicated environmental justice specialist. Darrell Rodgers, representing Public Health Seattle King County on the board, spoke highly of the amendment. “It’s a critical opportunity to advance environmental transportation system issues. The equity analysis has limited perspective currently on the harm and disparic treatment that’s happening with lower income communities, predominantly Black and brown ones especially, and this amendment would be very much needed as an opportunity to increase staff capacity,” he said.

Safety

Amendments around safety are another example of where the board was ready to adopt amendments highlighting broad, but primarily symbolic goals, indicating the board was much less ready to adopt changes that would impact the core way in which PSRC operates. Several board members urged PSRC’s Regional Transportation Plan to fully embrace a Safe Systems approach to eliminating serious injuries and fatalities caused by the transportation system. But the final amendment to the plan that was ultimately adopted didn’t do much of anything except acknowledge that the State of Washington still has a 2030 goal of getting to zero fatalities, and that the Safe Systems approach would be a part of that effort.

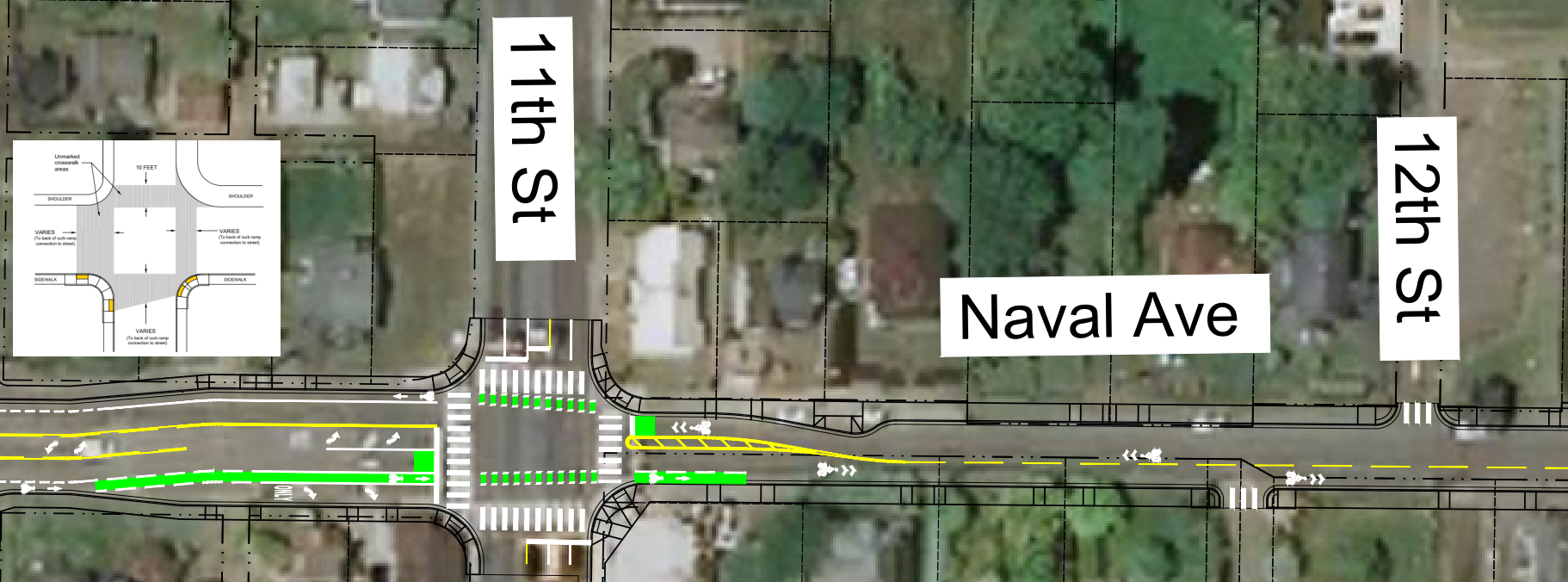

The board rejected another opportunity to increase safety for people who walk and bike by discarding an amendment that would have pushed projects funded by grants handed out through PSRC to construct bicycle and pedestrian facilities to a standard that is safe for riders of all ages and abilities. For example, the City of Bremerton is set to receive $1.6 million for upgrades to Naval Avenue that will add paint bike lanes along much of the corridor, but also transitions riders to sharrows, painted arrows indicating bicycles merge with vehicle traffic, which aren’t technically bicycle infrastructure.

Kitsap County doesn’t have any protected bike lane facilities in the entire county. Setting a higher bar to receive a high score in funding rounds could incentivize cities and counties to build out bicycle networks that prioritize protected bike lanes and other infrastructure investments that make biking safer and more comfortable for people of all ages and abilities.

The board also rejected another amendment that would require projects funded by PSRC grants to demonstrate how they would contribute to reducing the number of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) in the region. Ultimately, the fact that these proposals could have potentially impacted funding for specific projects in the member’s jurisdictions was likely the decisive factor in the board’s decision to discard these amendments. The desire to not rock the boat too much because the current process is funding projects in board members’ own jurisdictions might have been the Achilles heel of the entire process.

There may still, however, be some last minute amendments adopted before the PSRC Executive Board approves the entire regional transportation plan in May. But the fact that PSRC staff largely guided elected leaders toward the outcomes they envision as most expedient appears to have heavily tilted the entire amendment process away from the most substantive changes. The Regional Transportation Plan won’t be updated again until 2026, thus it is discouraging for advocates that some critical opportunities to reduce emissions and increase safety for pedestrians and cyclists were lost along the way.