American cities can glean many policy pointers from this highly livable French city, which has a delegation visiting.

This week delegates from Nantes, France, have been visiting Seattle to celebrate the two cities’ 42nd anniversary as sister cities. The delegates, Deputy Mayors Pierre-Emmanuel Marais and Mahaut Bertu, met with Seattle City Councilmember Tammy Morales to discuss strategies for creating affordable housing and transitioning away from cars, among other topics. Morales traveled to Nantes last December to learn more about the city’s approach to social housing, but during her visit she was also struck by the city’s achievements in opening up spaces to walking and biking.

“Part of what we learned while we were there is the city is really intentional about making a shift from this auto-reliant city to one with more small downtowns, more livable neighborhoods. That is the policy and program work we are trying to understand about how they operate,” Morales said.

I had the chance to chat with Morales, Marais, and Bertu, after they finished filming an episode of Seattle Within Reach, a series of conversations about affordability and accessibility that Morales is leading in preparation for Seattle’s 2024 Major Comprehensive Plan Update, many of the details of which will be worked out over the next year. Also, participating in this week’s episode of Seattle Within Reach were Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, Alderman for Chicago’s 35th Ward (Logan Square) and Miguel Maestas, Housing and Economic Director at El Centro de la Raza in Seattle’s Beacon Hill neighborhood.

For a little context, Nantes is the sixth largest city in France and it is located on the Loire River, not far from the Atlantic coast. Nantes has about 320,000 residents in the city itself, with another 650,000 residents living in the surrounding region. The city is denser than Seattle, with about 13,000 residents per square mile in Nantes versus about 8,800 residents per square mile in Seattle. More than 100 parks exist in Nantes, as well as system of green corridors known as the Étoile Verte, providing residents with ample access to green space. The presence of this greenery, along with nearly 50 kilometers of bike paths and an excellent public transportation system, have bolstered Nantes’ reputation as one of the most eco-friendly cities in France. In terms of social equity, a glance at a map showing percentages of social housing in Nantes, shows social housing comprises 25-35% of the city’s housing stock and that these affordable homes can be found across the city.

Officials from both cities were excited to rejuvenate the partnership between Nantes and Seattle, and Bertu emphasized in particular that she hopes collaboration between the cities can be broadened in the future.

“During our time here we visited museums. Maybe there will be exchanges that will continue through this sister city partnership that will bring real cultural connections so we can really feel that we are sister cities. This is another point that interests us,” Bertu said.

While acknowledging that French and American society and systems of governance are different in many respects, Seattle and Nantes share the goals of increasing housing affordability, furthering equity and inclusion among residents, and creating neighborhoods in which residents can meet their daily needs within a short walk or bike ride. Here are a few highlights from our conversation, with some references to the discussion that occurred during the Seattle in Reach episode as well. (The full episode is available online.)

Affordable Housing

Seattle and Nantes both face challenges related to housing affordability, but differences exist between each cities’ particular challenges and solutions. In over half of France’s urban areas, the law requires that cities plan so that 25% of their housing stock is affordable, similar to placing the entire country under inclusionary zoning requirements — though without exempting single family homes and older stock from calculations. This generally has been an effective model for bolstering housing affordability.

While some cities have opted to pay into a fund in order to opt out of building affordable housing within their own jurisdictions, Nantes has chosen to construct affordable housing onsite and is engaged in building mixed-income neighborhoods like the Ile de Nantes, an ambitious project that has transformed a former brownfield site into a mixed-used neighborhood in which 25% of new homes are affordable to households earning low-incomes and 25% of new homes are affordable to households earning moderate incomes. Even so, Marais and Bertu spoke of how gentrification pressures and rising prices have impacted the city in recent years, lengthening the waitlists for social housing.

In Seattle, rapid population growth has exacerbated housing scarcity, fueling an affordability crisis. Efforts to create transit-oriented development like Plaza Roberto Maestas, which offers affordable homes near the Beacon Hill Link light rail station, are aimed in the right direction, but the need far outpaces the housing being created. Miguel Maestas spoke about the work El Centro de la Raza engaged in to make this housing a possibility and the support it receive from Sound Transit and the City of Seattle. The U.S. government, however, is far less active in supporting the creation of affordable housing than is the French government.

“There really truly is a whole industry around affordable housing, and while I’m thankful there are organizations like El Centro de la Raza that are willing to jump through hoops to create housing for working families, it seems to me like there are better ways for us to do it,” Morales said.

Bertu, however, also mentioned being impressed by how public-private partnerships have contributed to the creation of affordable housing in Seattle, citing the example of Mary’s Place, which offers shelter to women and children experiencing homelessness and receives funding from Amazon. In France, the private sector typically does not engage in efforts like creating emergency shelter or affordable housing.

In regards to Chicago, Ramirez-Rosa highlighted a trend that truly differentiates the city’s affordable housing challenges from Seattle’s. Trendy neighborhoods like Logan Square have seen many small apartment buildings converted into single-family dwellings over the last couple decades.

To fight this loss of naturally occurring affordable housing, residents of Logan Square, the ward Ramirez-Rosa represents, were able to successfully advocate for a policy restricting single-family conversions in areas near the wildly popular Bloomington Trail (606). Even so, housing prices remain a concern for low- and moderate-income households, and racial and economic segregation remains a major problem. Statistics suggest that the Chicago metro area is the fourth most racially segregated in America, and while the city has inclusive zoning policies as well, many developers prefer to pay into a fund rather build the affordable housing onsite. Much of the affordable housing is then built in historically poorer areas in the South and West sides of the city. In Logan Square, however, residents were also able to update its inclusive zoning policy to ensure the affordable housing resulting from new development is built within the neighborhood.

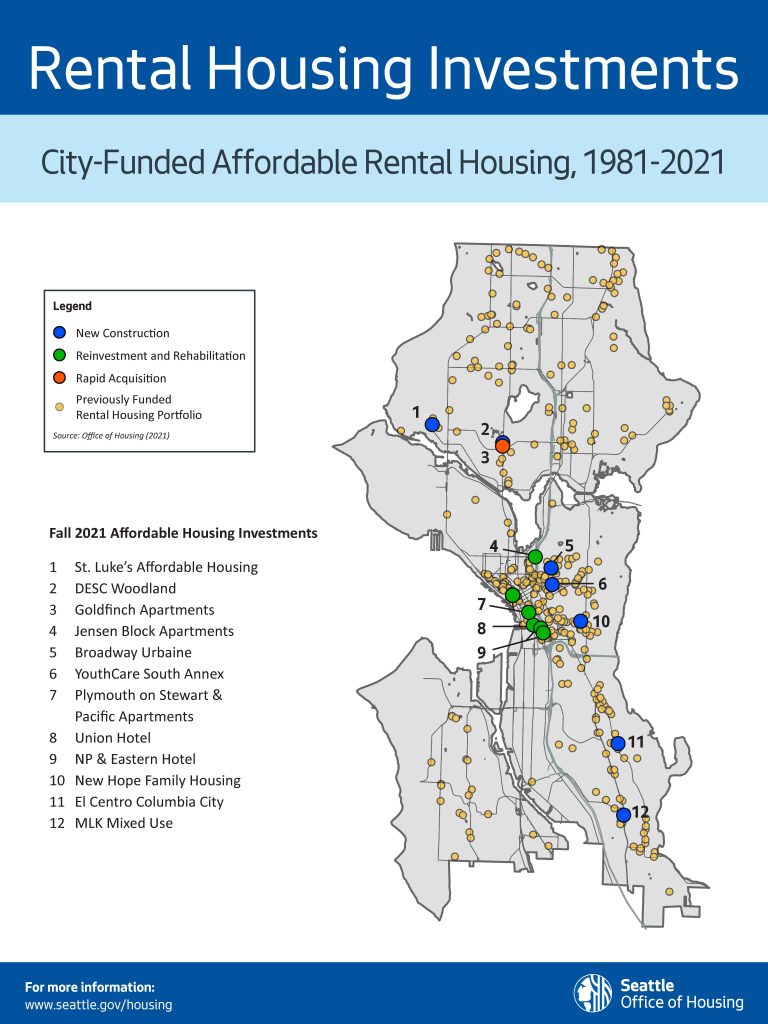

Under Seattle’s inclusionary zoning policy, most developers have also preferred to pay into a fund rather than include affordable housing onsite. However, while economic disparities and racial segregation exist in Seattle neighborhoods, their magnitude is less severe than in Chicago. With the caveat that many affordable housing investments are built in or near the downtown area, affordable housing investments appear to be being created in various areas of the city zoned for multifamily development.

Equity and Inclusion

Discussion of affordable housing overlapped quite a bit with the theme of equity and inclusion; however, there were two major points made by the delegates from Nantes that differentiated the city’s approach, the first of which was the need to build more social housing or mixed-income housing in wealthier areas of the city. Doing so is a priority in Nantes to help ensure that lower-income households are not confined to living in only certain neighborhoods and enjoy equal access to opportunities and amenities. In Seattle, on the other hand, zoning ordinances that restrict multifamily housing from being built in most affluent areas make it all but impossible to even consider building affordable housing there.

But the most striking difference was related to the Nantes’ work to become an anti-sexist city, which was described in depth by Bertu. Combatting sexism through city policy and planning is a major priority in Nantes, and examples of how this ideal is being put into action are diverse. From making sure that all residents live within a 15-minute walk of public menstrual product dispensers, to designing school and public play spaces to foster interaction and engagement between boys and girls, to keeping women’s safety concerns in mind while designing and landscaping public parks, in Nantes the topic of combatting sexism filters into all decision-making processes.

“This is for all of us,” Marais said. “And for members of the municipal council, including us men, we’ve also incorporated this kind of reflection so we can keep moving forward, because we still have work to do.”

Both Marais and Bertu complimented Seattle’s achievements in community engagement and outreach, especially with disenfranchised and vulnerable residents. In Nantes, people are able to contribute to the planning process by joining their neighborhood councils, which is not always accessible given the commitment it entails. However, the delegates did also highlight that Nantes is working toward a more participatory style of democracy and actively seeking new ways to engage with residents.

The 15-minute city

The importance of the 15-minute city in Nante’s current planning efforts emerged earlier in discussion and was a point frequently returned to throughout it. Nantes envisions itself as becoming a city composed of many small city centers where residents can meet most of their basic needs. In Nantes, this is envisioned as having access to at least 12 services like grocery stores, healthcare providers, cultural spaces, parks, and public transportation, etc., within a 15-minute walk of one’s home. According to Marais about 95% of Nante’s population already have access to this level of service.

While some Seattleites, especially those living in urban villages, enjoy a similar level of walkability, the number is nowhere near as high as in Nantes. In Seattle, urban villages often appears as islands of walkability in a sea of dispersed housing, and highways and busy roads pose more interruptions and dangers to people walking.

Nantes also has an innovative bike share model called bicloo that makes it easier for residents to transition to biking for transportation by allowing both short and long-term rentals (up to one year) at affordable prices. Currently about 3% of trips take place by bicycle in Nantes, but the city hopes to increase that number to 12% in future years.

Morales raised the issue of gentrification arising from a transition to a 15-minute city model as neighborhoods gain new amenities, but that phenomenon appears to be much more of a threat in the U.S. than in France.

Gentrification spurred by the aforementioned Bloomington Trail in Chicago is a good example of the challenge that American cities face in this area. Because we have built so many American cities to be unwalkable, residents’ desire for access to places that are convenient for walking and biking can then lead to a spike in local housing demand when new amenities are introduced, leading to subsequent increase in prices. Nevertheless, France shows that by making walkability more ubiquitous — and by building out major infrastructure projects to support walking and rolling — American cities should be able to mitigate gentrification’s worst impacts as they become easier to navigate without cars.

Learning Opportunities

Morales said that she hoped that the current exchange between Seattle and Nantes could led to a “reboot” of the relationship between the two cities. While Seattle often looks to neighbors like Portland, Vancouver, BC, and San Francisco for inspiration and perspective, engaging with the delegates from Nantes — and also bringing in a representative from Chicago — helped to introduce new ideas for longstanding challenges, while also highlighting similarities that span countries and continents.

“We are confronting the same major issues, and we share the same values like democracy,” Marais said. “Continuing this sister city partnership allows us to say that we have these same values and that’s it above all.”

Author’s note: The interviews with Deputy Mayors Pierre-Emmanuel Marais and Mahaut Bertu were conducted in French. The author provided French to English translation for this article.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.