On Monday, Governor Jay Inslee boarded a small boat with U.S. Senator Maria Cantwell and Representative Marilyn Strickland to tour the mouth of the Nisqually River in Thurston County. Interstate 5 crosses the Nisqually at the southern edge of the Billy Frank Jr Nisqually National Wildlife Preserve, close to the river’s outlet to Puget Sound, and the Governor’s visit signals significant interest in reassessing the future of the highway there.

Earlier this year, the Tacoma News Tribune detailed the corners that the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) cut while they were constructing I-5 through the Nisqually river valley in the 1960s. Rather than being constructed on piers across the river delta, the highway was constructed on fill, restricting where the river could flow. That decision has substantially increased the risk of flooding today. In 2020, the U.S. Geological Survey released a report noting that a bend in the river, slowly shifting, could reach I-5 within 17 to 30 years. That fact was ultimately what brought the Governor and federal lawmakers to the river on Monday. “It is necessary that we do this now,” Inslee told reporters.

The reality of climate change will be seen in the Nisqually delta sooner rather than later. But will the proposed solution being advanced by the state, intended to create resiliency and improve the health of the river ecosystem, come with broader environmental impacts of its own?

WSDOT is in the process of expanding I-5 in numerous places right now, including downtown Seattle, over the Puyallup River in Tacoma, and over the Columbia River between Washington and Oregon. Now the department is moving forward a proposal, that comes with a $1.06 billion preliminary cost estimate, prepared in advance of Governor Inslee’s site visit on Monday, to build two 5,000 foot bridges spanning the Nisqually River Delta. Those bridges would come with four lanes in each direction, three for general purpose traffic and one for high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) traffic. Also, currently envisioned is a 10-foot shared use path for people walking and rolling between Mounts Road and Marvin Road.

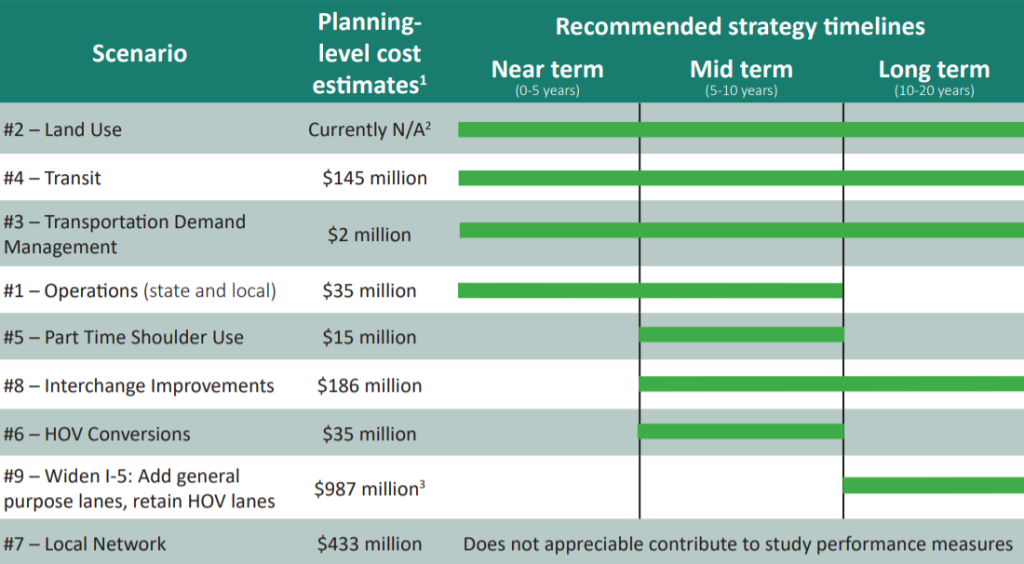

Several years ago, the state legislature directed WSDOT to study alternatives to improve I-5 through the entire Nisqually River Valley, between Tumwater and the I-5 exit at Mounts Road just north of the wildlife refuge. In 2020, the department, in coordination with the Thurston Regional Planning Council, released a study that analyzed a set of proposed changes to I-5 through the valley. Each change was built on the previous one, so hardly any of the concepts were studied independently.

After a suite of smaller modifications to the road network, only one of which would directly impact I-5 itself, the second improvement studied was adjusting the current land use in Thurston County. If this seems unusual for a highway study, that’s because it is. Land use is generally not fully analyzed as a tool in the toolbox when it comes to major highway projects — usually the best treatment land use gets in these discussions is lip service.

Those land use assumptions discard the status-quo plan for Thurston County through 2050 and instead look at “visionary” goals from the Thurston planning council’s Sustainable Thurston plan. It assumes that by 2035, 72% of all households in Thurston County’s cities, towns, and unincorporated growth areas will be within a half mile of an urban center, corridor, or neighborhood center where getting around without a vehicle on some trips is more feasible. It also assumes that through that year, only 5% of new housing units permitted in the county are within rural areas.

The result? Apart from providing the best outcome in terms of access to jobs and commercial services, travel times on I-5 were shown to improve relative to current conditions. It was also the best performing scenario studied in terms of greenhouse gas reduction and reducing vehicle miles travelled (VMT).

The report also looked at the impact of adding an additional lane to I-5 through the corridor, bringing the total number of lanes to four in each direction. It looked at this additional lane as both an high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lane and a general purpose lane. These two alternatives received “the most negative score possible” in terms of environmental impact, with the HOV lane option showing a 2.1% increase in greenhouse gases and the general-purpose lane option showing a 2.7% increase. The land use option was modeled to reduce emissions by 1.6%, which means that adding a lane to I-5 through the Nisqually Valley was forecast to completely erase decades of gains that could come from improving land use in Thurston County. When people talk about housing and transportation being two sides of the same coin, this is a crystal clear example.

In terms of cost, the expansion of the highway was the most expensive strategy by far, with a planning-level cost estimate of nearly $1 billion. Ultimately, the expansion studied ranked fairly low in the report. “This strategy had relatively low incremental benefits after other less costly and invasive strategies had already been implemented in the model,” it noted.

In March, WSDOT produced a much longer report on the corridor’s Planning and Environmental Linkage (PEL) study, one that doesn’t even use the word emissions at all. It too notes the high overall effectiveness of land use as confirmed in the prior report but noted that WSDOT would not be incorporating land use into further study. “The local improvement scenarios…are not reviewed in the PEL study because WSDOT would not be the lead NEPA/SEPA agency for these actions,” it states. Land use (and transit, another element analyzed in the earlier report) aren’t WSDOT’s jurisdiction, so they won’t get studied alongside the proposed modifications to I-5, even though all of the information available indicated they were likely the most effective solutions.

Constructing the new river bridges with four lanes in each direction will make expansion of the rest of I-5 to match its width nearly inevitable. Last year, Bill Adamson with the South Sound Military and Communities Partnership told the Washington Transportation Commission that it is pushing for the entire highway to be expanded from three to four lanes to “add much needed capacity to handle growing traffic concerns,” and that the full range of capacity expansion projects they envisioned could cost as much as $4.2 billion dollars, nearing the full estimated cost for the Interstate Bridge Replacement, which includes high-capacity transit. Unlike that project, costs wouldn’t be split with a neighboring state.

“I know these are big numbers, but there is no choice,” Inslee said Monday. There is a choice on whether to move forward with expanding I-5, and it’s a completely separate choice from deciding whether to improve flood resiliency and the river ecosystem. The data is clear: Washington will not be aligned with its prior commitments on greenhouse gas reduction if it moves forward with expanding a highway in the name of climate resiliency.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.