Earlier this week the House Our Neighbors! coalition filed a petition for a ballot initiative asking Seattle voters to weigh in on the creation of a public developer tasked with creating and owning social housing in Seattle. Unlike most other forms of nonprofit affordable housing in the city, social housing created by the public developer would be available to both middle-income and low-income households, in this case people earning from zero to 120% of area median income (AMI). If House Our Neighbors succeeds in gathering enough signatures to meet the threshold, the measure will appear on the ballot in November. If approved, a public developer could significantly alter the housing landscape in Seattle down the road.

In this article, I’ll provide background information about the social housing model, dive into details about how it would work under this particular public developer initiative, and explain what it will take to make it a reality.

Social housing is broadly understood to be housing that remains outside of the private market, making it affordable over the long-term and free from the whims of private landlords and the mercurial housing market. It is found in a variety of different housing ownership, subsidy, and regulation models throughout the world, particularly in Europe and South America. In these areas of the world, social housing’s goals often go beyond permanent affordability to encompass democratic resident control and aspirations toward social equality. As you’ll see later on in the description of the House Our Neighbors coalition’s model, this philosophical approach is very much alive in their vision for social housing in Seattle.

When it comes to providing examples of social housing at work, Vienna, Austria is often the first example cited. After recognizing that housing prices were soaring out of reach for city residents back in the 1980s, Viennese public officials decided to enter into collaboration with limited-profit private developers to increase affordable housing production. While the private developer builds the housing and retains ownership of it, it is required to follow a city-regulated process in which half of the housing created is reserved for low income residents, while the other half is made accessible to moderate income residents. Rents are capped at 20-25% of residents’ incomes, and all of the housing communities are mixed-income to promote social and economic integration.

The approach has been extremely successful for Vienna. Today more than 200,000 permanently affordable homes are owned by limited-profit developers and thousands of new homes are added annually. Vienna’s social housing has earned international recognition for its quality with residents participating in the design process for some projects and architects competing via design contests. In addition to its social housing, Vienna also has roughly 220,000 publicly owned affordable homes, further sheltering residents from market fluctuations. The quality and affordability of housing in Vienna is a major reason why the city has ranked number one in the world for quality of life according to the Mercer Index for ten years in a row.

While Vienna has earned international accolades for its work in social housing, it’s important to point out that the model has been adopted in other countries as well. Singapore, Canada, and France, among others, have all taken their own unique approach to social housing. According to Tiffani McCoy, Advocacy Director at Real Change Homeless and co-chair of House Our Neighbors, in the United States, the model has been put into use only once, in Montgomery County, Maryland. However, there is a growing national movement to bring social housing here. While developing the text of the ballot initiative House Our Neighbors consulted with Hawaiian State Sen. Stanley Chang, an outspoken supporter of social housing, as well as organizers in California like East Bay for Everyone who are working to create social housing using a statewide public sector developer.

McCoy and other members of the House Our Neighbors coalition hope that Seattle will lead the way by creating a public developer model that can be replicated elsewhere. “This is not utopian,” McCoy said. “It’s a model that works in so many different parts of the globe. We just haven’t done it in the United States yet.”

A different approach to affordable housing

The social housing that would be developed through the House Our Neighbors coalition’s public developer plan would differ in several ways from affordable housing currently being created in Seattle.

McCoy shared with The Urbanist a one-pager describing how the ordinance that would be created by the ballot initiative would work and what goals it aspires to achieve.

Social Housing Initiative One Pager by Natalie Bicknell on Scribd

When I asked McCoy about the primary benefits of the public developer model, she was quick to point out that the effort was fueled in large by an a desire to shift housing in Seattle out of a “scarcity mindset” in which housing goals like affordability, environmental sustainability, and respecting workers rights are often placed in competition. “We can’t allow this false division to keep going,” McCoy said.

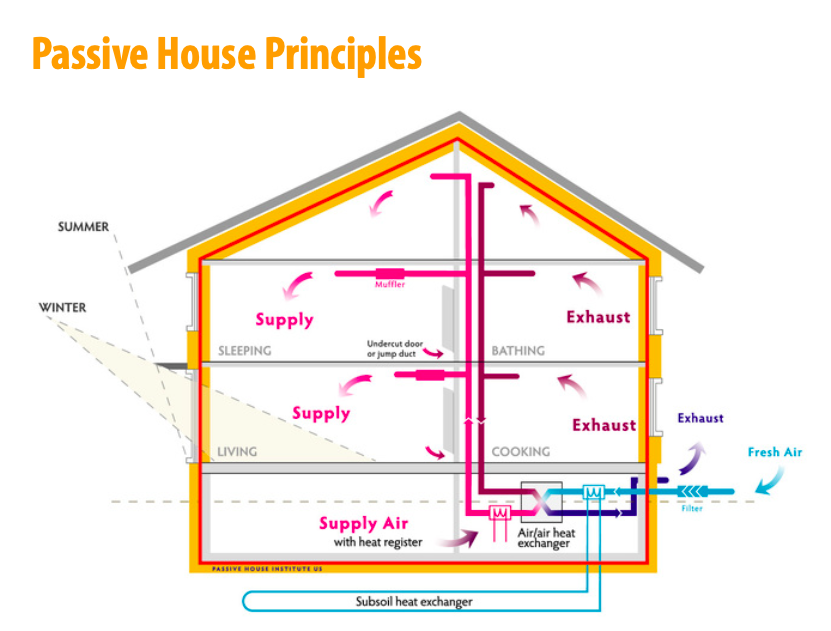

In regards to environmental sustainability, housing created by the public developer will be designed to meet passive house standards, which reduces both their energy footprint and operating costs.

Passive house architect Mike Eliason, Director of Larch Lab and a columnist at The Urbanist, was excited about the idea, expressing support online.

“This is amazing, and equally as incredible was the push to have this initiative adopt Passivhaus as the baseline standard for construction, with a credentialed Passivhaus professional to sit on the PDA’s board,” Larch Lab tweeted. “There is nothing like this in the US — it would be transformative.”

Another one of the House Our Neighbors coalition’s goals is to have all of the housing built by unionized trade and construction workers. While McCoy shared that it was not possible to include that labor requirement in the language of the ballot initiative, the coalition judges that the presence of a rank and file union member on the board of the public developer will ensure that contracting work to labor unions is prioritized. The 13 member public developer board is intended to foster equitable leadership and a majority of seats (seven) will be held by democratically elected social housing residents.

Start up financing will be needed to kick off the public developer’s operations. While ballot initiative requires that the City of Seattle contribute staff and office space to the public developer for the first 18 months, it is not currently known where start up funds will be sourced from in part because a public developer would not have the authority to impose taxes on its own. Organizers are currently working with an economist and a lawyer to explore funding options, and ensuring those funds are raised from progressive revenue is a top priority, McCoy said. The coalition doesn’t envision the public developer will be applying for federal housing grants. This is because federal housing grants come with strict income requirements for future tenants, generally stipulating tenants earn 80% or less of AMI.

One of the goals is for social housing to create mixed income communities, and because of this social housing offers a more financially self-sufficient model than many of types of affordable housing. While McCoy acknowledged that it is unlikely that the public developer would become fully financially self-sustaining, the coalition anticipates that it will be less dependent on outside funding than other government and nonprofit affordable housing models. This is because the public developer will have the authority to issue bonds in exchange for loans, which would be paid back by rental income. Although residents will be charged less than 30% of their monthly income in rent, House Our Neighbors is banking on a cross-subsidy effect in which the revenue from middle-income tenants will pay back the loans, guarantee future loans, and offset the lesser revenue coming in from low-income tenants.

Publicly owned land will also factor into the affordability of future social housing created by the public developer. As part of the ballot of initiative, the City of Seattle will need to undergo a feasibility study and consider whether the land should be sold to the public developer before proceeding with the sale of the land.

At this point, you may be considering how the public developer could impact the work of developers like the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) who are already actively engaged in the creation of affordable housing Seattle.

Right now because of the requirements attached to funding sources, federal tax credits in particular, much of the affordable housing in Seattle is being created for people who are very low income and often exiting homelessness. Additionally, a significant amount of this housing is permanent supportive housing, which in provides onsite care for people with addiction, mental health, or other health and access needs. While there is definitely a need to continue to increase permanent supportive housing in Seattle, organizers at Real Change have also noted that few housing options exist for very low income people who do not have special needs — or who have stabilized in supportive housing and ready to move to housing without wrap-around services. The public developer could meet this demand. “We are not competing with LIHI or other nonprofit developers,” McCoy said.

The House Our Neighbors coalition first started as a response to the failed “Compassion Seattle” charter amendment initiative which sought to address homelessness — or at least make it less visible — by rapidly creating “emergency housing” geared at temporarily housing the chronically homeless. The coalition believes a public developer is the proper response because it gets at the root problems of housing scarcity and a lack of housing designed to be affordable rather than a good investment vehicle, which are driving factors for Seattle’s housing crisis.

Still without increased funding for affordable housing appearing on the city, county, or state level, it is likely that the public developer would be forced to compete against nonprofit developers for at least some local funds. That’s why developing a progressive revenue source for affordable housing is considered important for its long-term success.

McCoy envisions other changes needing to take place as well for the city to fully capitalize on the public developer’s potential. “We are not going shy away from the fact that we have to change our zoning,” McCoy said. “We also have to reassess how design review works.” Both the need to increase Seattle’s zoning capacity and reform the design review process to avoid costly project delays are points that have been frequently cited by housing advocates for years, but still progress on those goals has been hindered by staunch opposition and lukewarm equivocating.

Making a public developer a reality

The first step toward making a public developer a reality in Seattle will be to ensure the initiative makes it on to the November ballot. To do so, roughly 27,000 signatures from registered Seattle voters will need to be gathered, an amount equivalent to 10% of the total votes cast for mayor during the most recent election, plus a cushion to account for challenged ballots. It could take about 35,000 signatures to be safe. The House Our Neighbors coalition is currently seeking volunteers to help with signature gathering efforts.

If the petition amasses enough signatures, and does not get derailed by a successful appeal, the decision will go before Seattle voters. McCoy is optimistic that Seattleites are ready to try something new when it comes to solving our city’s housing and homelessness crisis. For people who want to make a difference, her first piece of advice to get involved with housing advocacy efforts.

“Every year that goes by more people enter into homelessness,” McCoy said. “It’s important to remember we can stave these things off and invest in housing as a human right.”

Correction: This article was corrected on 4/1/2022 to remove a reference to Community Roots Housing as a nonprofit developer. Community Roots Housing was founded by Capitol Hill housing activists and established as a Public Development Authority by the City of Seattle in 1976.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.