Earlier this month, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) installed two new signs near crosswalks in the High Point neighborhood. The blue signs give drivers a “report card” on how often everyone collectively driving through the intersection is yielding for people trying to cross, a requirement they’re legally obligated to follow. The first week featured a 46% compliance rate at SW Morgan Street and 34th Avenue SW. By the next week, it had declined to 28%. According to SDOT, this report card will be populated using a relatively small sample size of twenty-five drivers once per week, manually counting which drivers yield.

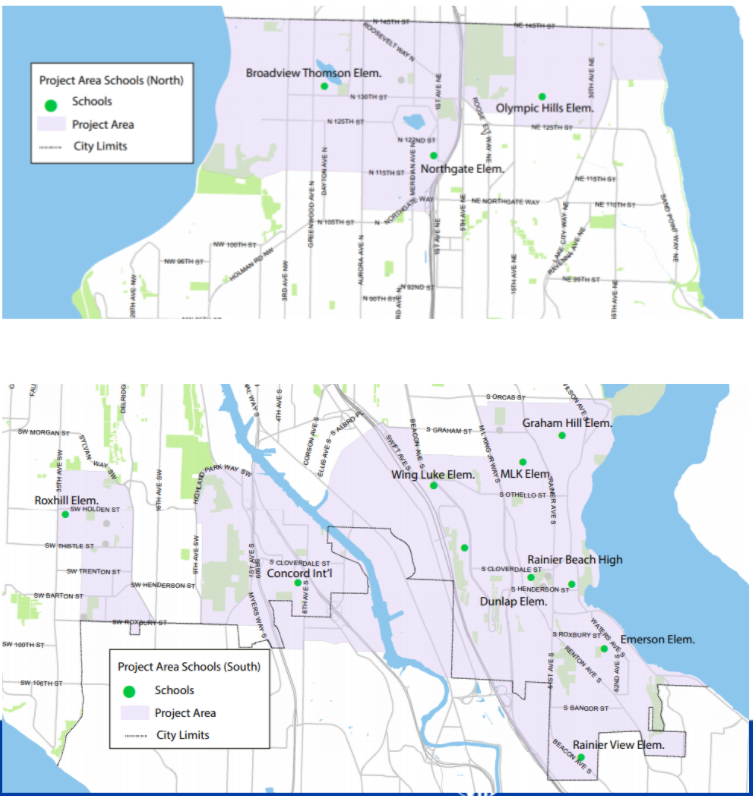

The signs are just one early aspect of Seattle’s next major public awareness campaign on traffic safety: Safe and Slow Seattle. Utilizing a grant from the Washington Traffic Safety Commission along with some local Vision Zero funding, this campaign is expected to last two years and will focus on two aspects of traffic safety: informing drivers of their duty to stop at both marked and unmarked crosswalks, and of the benefits that come from obeying lower speed limits. The speed limit campaign will have a citywide focus, educating drivers on arterial streets that almost exclusively have a 25 miles per hour speed limit, of the benefits of those lower speeds. But the crosswalk campaign will be focused in particular in areas directly around schools with a higher-than-average percentage of students receiving a free or reduced price lunch, students learning English as a second language, and nonwhite students. After this roll out in High Point, the signs will move to Rainier Beach and other neighborhoods.

SDOT might prefer to spend the entirety of a traffic safety commission grant on permanent infrastructure, like rapid-flashing beacons to increase visibility of crosswalks, or even new sidewalks, but they can’t. Funds distributed through the state traffic safety commission in most cases are required by federal law to be spent on things like public awareness and education campaigns, or on increased police enforcement of traffic laws. For nearly two years, SDOT has not been partnering with the Seattle Police Department on traffic enforcement activities. “It’s time to daylight the uncomfortable reality that relying on an enforcement-heavy approach in transportation can also lead to disproportionate financial impact, injury, and death for Black and brown community members across our city and across the country,” Sam Zimbabwe, SDOT Director at the time, told a city council committee last year.

In creating these new driver report cards, SDOT is adopting a model tried in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where similar signs were deployed as part of a pedestrian safety campaign. Those signs were also part of a broader campaign that included education, enforcement, and additional engineering aspects. Results showed marginal improvements: compliance increased around 10% in both Minneapolis and Saint Paul, where compliance rates were already uneven. But police issued thousands of warning and citations as part of the enforcement aspect of that campaign, something that will not happen in Seattle. In the last fiscal year, the Seattle Police Department was set to receive $73,000 in grants from the traffic safety commission for enforcement activities of its own, including high-visibility enforcement around impaired driving, so it’s not as if SPD has been removed from conducting enforcement activities in the city entirely.

Safe and Slow Seattle is just the latest in a long line of public safety media campaigns that have attempted to influence the culture on the city’s streets. Since the city’s official adoption of Vision Zero in 2015, most traffic safety campaigns have been focused on the Vision Zero branding, including a widely-viewed distracted driving campaign 2016. That campaign was followed by a strengthening of Washington State’s distracted driving law, so its long term effects are unclear.

Prior to Vision Zero, the major safety campaign, launched under Mayor Mike McGinn, now fighting for pedestrian safety nationwide as the executive director of America Walks, was the “Super Safe” campaign. That campaign was a broad-based education campaign that sought to empower road users to create a “culture of empathy.”

So is there any evidence that the media campaigns that SDOT has been conducting for many years now have had a sustained impact on the city’s driving culture and its safety outcomes? If it has, it’s clearly not been enough to push back on national trends that are causing a severe escalation in serious injuries and fatalities everywhere — vehicle design that is more likely to cause severe trauma to pedestrians, traffic demand changes during the pandemic that are influencing rates of speeding. With 2021 the deadliest year on the city’s streets since 2006, it looks like any gains in influencing the city’s “culture” have vanished.

More broadly, a comprehensive look at traffic safety media campaigns between 1975 and 2007, analyzing campaigns from twelve countries, showed an overall reduction in collisions of 9% that can be attributed to education efforts. But that analysis of the broader studies showed that the long-term effects were largely unknown. As the city shifts more and more toward a full embrace of the Safe Systems approach, which de-emphasizes the role of the individual road user in favor of focusing on the system and how failure is addressed, the idea of truly influencing the culture seems to be receding from view. In the meantime, with funds available for education and outreach, SDOT seems to be gearing its campaign efforts more and more narrowly. The results will likely speak for themselves.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.