As we emerge from pandemic and look towards returning to offices, a question starts to come up. “What’s for lunch?” A recent impromptu survey of several downtown Seattle restaurants suggests it’s very difficult to get out without forking over around $20 a person.

The overloaded half pastrami and soup at Market House Meats on Howell is $16 ($5 beverage from elsewhere localish). Lunch for three folks of a nacho plate and two fish burritos plus beverages at Blue Water Taco Grill in Seattle Center hit $60. The Massaman curry at Kati Vegan Thai in Cascade is $17 and worth it. (The total bill was a bit higher because the fantastic and delightfully spicy cauliflower bombs got involved.)

Twenty dollars is kind of a psychic boundary. It’s deeply in that second dollar sign on Yelp. It’s the difference between grabbing lunch once a week as opposed to three times. While it is not the most obvious change to Seattle’s food scene, crossing that $20 lunch may be the most impactful. Will people go out for lunch and support local businesses when food regularly hits that mark?

Everything is pricy

Year over year, the cost of food has increased. This is true at home, where the price to eat rose 12.1% over 2021, led by meat, poultry, and nonalcoholic beverages. It’s also true at restaurants where the price rose 6.5% for many of the same reasons.

The pandemic also had some interesting effects on our eating habits, beyond simply stress feeding. Closing restaurants and rising wages have changed how many places there are for food, and what of the money goes too staff. The rules of when to tip and how much are absolute chaos. We’ve been buying family–sized meals for the last two years. Anything left over could go straight into the home fridge for later. Just like at the beginning of the pandemic, it took a while to right-size toilet paper and shift it from corporate sizes to home bathroom rolls. It will take time to right-size meals too.

Of course, there will be a lot of handwringing about whether this is yet another thing that represents a lost Seattle or how much the liberal City Council is ruining the business climate.

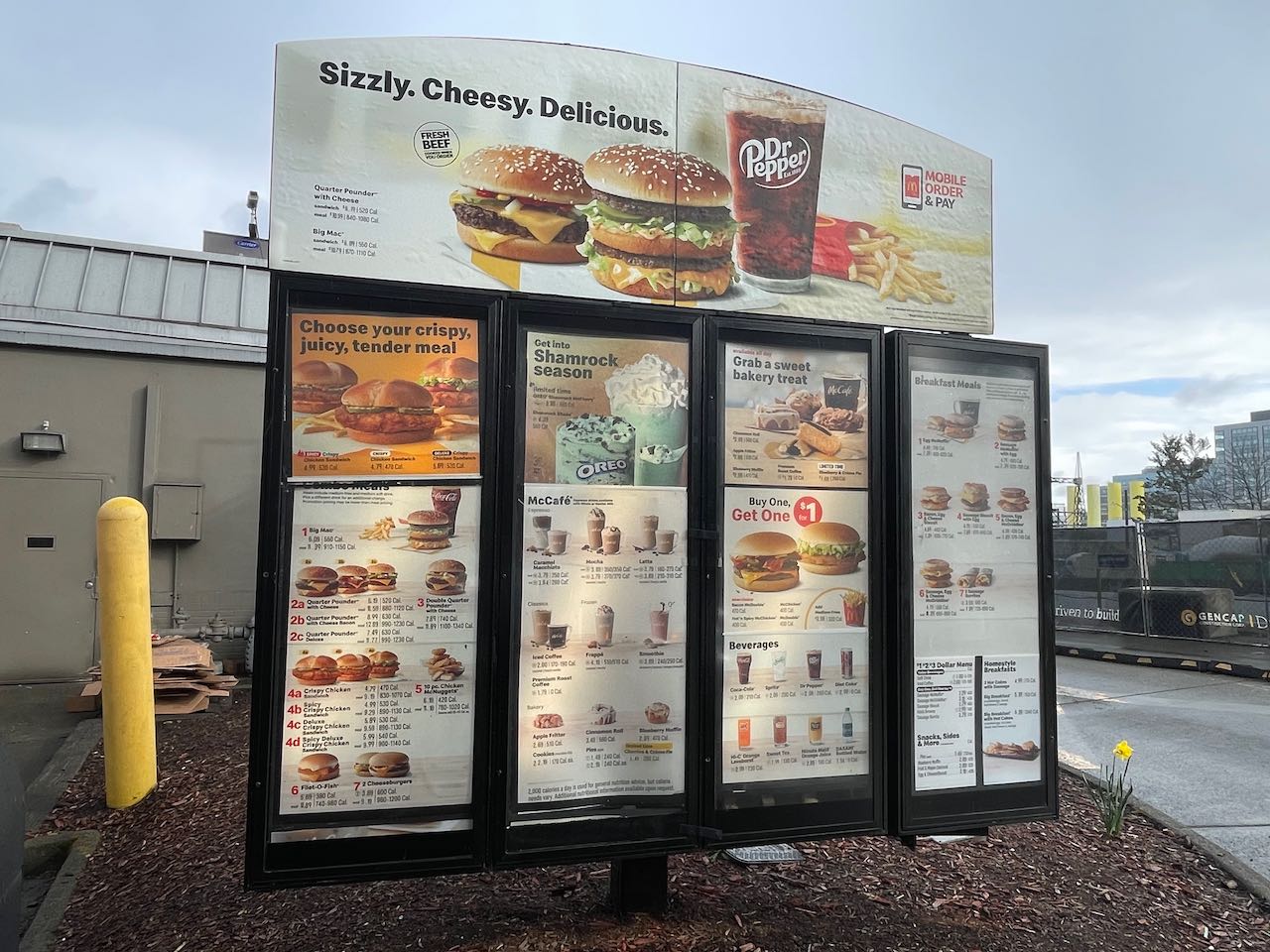

Comparing prices for something like McDonald’s inside and outside the city shows the impacts of local policies are marginal. Really, the prices are all over the place. Downtown, most burgers are 50¢ more for the sandwich and $2 more Downtown for the combo. However, all the McChickens are cheaper downtown. The significant bump in the combo meals can be attributed to Seattle’s tax on buckets of sugar. Where that tax doesn’t apply, such as milk based drinks, the price on beverages is comparable. Both locations include the $1 second sandwich deal.

As for losing personality, the effects of food prices are being seen across the country, even among iconic cheap food joints. New York $1 slices of pizza are no longer a dollar. The regular Geno’s cheesesteak sub in Philly is now $12. A baseline Italian Beef at Al’s in Chicago is just over the $10 mark. And those places pour out their specialties at scale for locals and tourists. The closest thing Seattle has to a local iconic food is the neighborhood teriyaki spots, and many of them are at a cheesesteak comparable $12 and $14 for their bowls.

Punk rock to the core

More than food itself, the landscape of restaurants downtown has changed. Without the ebb and flow of daily workers, restaurants have reduced hours or closed completely. The lively food truck scene of the last decade has been very quiet.

But Jonathan Amato, Managing Director of SeattleFoodTruck.com is optimistic. “I think the city is resilient and strong. It’s like after the Great Recession. People came back with a vengeance. Chefs aren’t going away.” The group organizes and schedules for over 400 food trucks in the Seattle area, including throughout many corporate campuses.

For two years now, those campuses have been ghost towns and food trucks have scrambled to survive. The numbers for how many food trucks closed versus how many are hibernating is unclear. What’s startling is how those coming back will not include big names like Skillet and Nosh. Both longtime cornerstones closed their mobile operations. “It’s hard to see the veteran trucks shut down,” Amato says. “They shaped Seattle’s street food community and kept things moving. They were the people you went to with questions.”

Over the course of the pandemic, SeattleFoodTruck.com helped food truck operators pivot. The organization organized first responder meals at Boys and Girls Clubs around town and was invited by neighborhood groups to provide socially distant food options in their communities. The group also leaned into the diversity of food truck operators, 70% of whom are women and people of color. Many of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans needed translation for those whose first language is not English, and everyone needed aid navigating the new programs.

Now the industry is pivoting once more. “We’re not doing homeowner associations as much, we’ve seen a step back. The brewery circuits and tap houses are going way up. And we’re seeing a start to get back into office life,” he said. Even through the on-again, off-again rules, Amato has seen food trucks prevail. “One step forward, two steps back,” he laughs. People are also rescheduling events that have been put off for two years, like weddings, as well as hosting employee welcome backs with food trucks catering the party.

Food trucks get hit with some unique higher prices. Many of the costs of food are increasing because of the cost of gas. That’s a double whammy when your mobile restaurant also uses gas. Credit cards take a larger chunk out of food trucks because they use mobile payment systems. Brick and mortar restaurants are charged credit card fees at one rate for their dedicated installed phone connection. Food trucks work with vendors that may charge double those fee simply because the transaction occurs over a cellphone.

Together, does this total up to a more expensive lunch? Amato thinks so. “Yeah, it’s Seattle. It’s not Des Moines. Everything is a bit higher. The thing about that $20 burger is the owner is not hopping in a corvette with the profits. These food trucks are working 80 hours a week and on that truck every single day. They’re trying to pay a wage to their employees. They’re not balling out of control.”

Just dessert

Between razor thin margins and a timid return to daily life in the office, where does that leave cheap lunches in downtown Seattle? For the time being, probably hibernating with some of the food trucks. Walking downtown, one sees more sidewalk signs advertising happy hours than lunch specials at the moment.

But the existence of any such sign is a testament to the creativity and resilience of the people who power Seattle’s restaurant scene. Each one has lived through this pandemic hellscape with the rest of us, and many with the added burden of wondering what employment looks like with each new lockdown. To ask the restaurants to come back to pre-pandemic costs like nothing happened is unreasonable. This creative industry is going to come up with new ideas. These are the folks who came up with late night happy hours during the Great Recession and spent the last two years in yurts. They know what they’re doing. It will just take some time and some consistency.

And, to be fair, we may also be out of practice as customers. It’s not just the unhinged person screaming at a clerk about mask requirements who isn’t doing the behavior-in-public thing that well. There’s an excitement to finding oneself back at a restaurant after a long time, so yes, I’ll have the double burger and fries and shake and probably get one for the road too. We’ll settle down and get back into practice, and the meals and portion sizes and lunch specials will follow.

When we do, we’ll find Seattle’s roster of amazing restaurants has some worthy new additions where a $20 lunch is probably worth it.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.