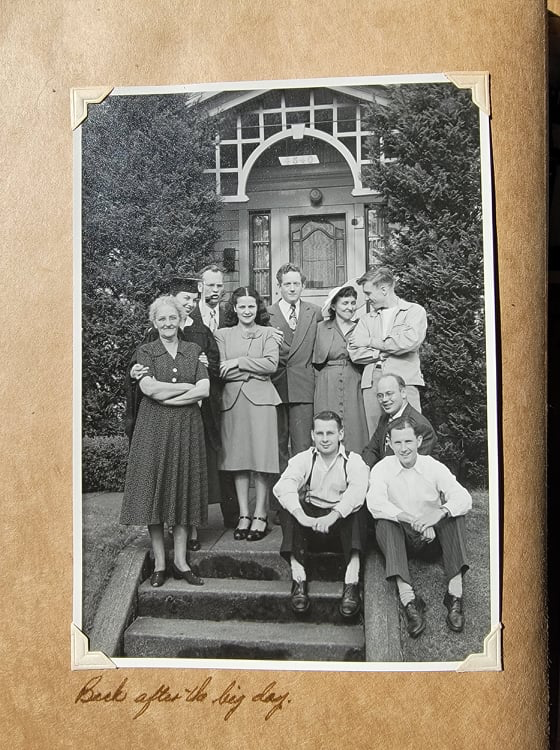

Beginning with my great grandmother, three generations of women in my family lived in a craftsman home that has since been flattened into the public parking lot next to the Trader Joe’s in the University District. My grandparents met on that very doorstep. And you know what? That the house is gone is just fine.

I understand the love of a place. I feel comforted in any place where salal grows. I even understand resistance to change and uncertainty, although they too are as certain as death and taxes. Seattle has a rich history that should be celebrated, grieved, explored, and even questioned. The craft of exploring the stories of those before us is a vital thing. But to explore history as a means to an end, especially one that would prevent change rather than encourage growth with intention, may perpetuate social problems by preventing forward progress.

Historic Wallingford is a nonprofit organization working toward a federal historic designation for an area encompassing roughly 1000 structures on the claim that the spatial character from the period of 1900-1936 has been well-preserved. While it is certainly the case that some architectural features remain, this designation would work to protect a remarkably narrow concept of a complex history. When I hear about this preservation effort, I find that the view of what is ‘historic’ and therefore worth protecting cherry-picks a version of history that ignores important realities, both from the past and today.

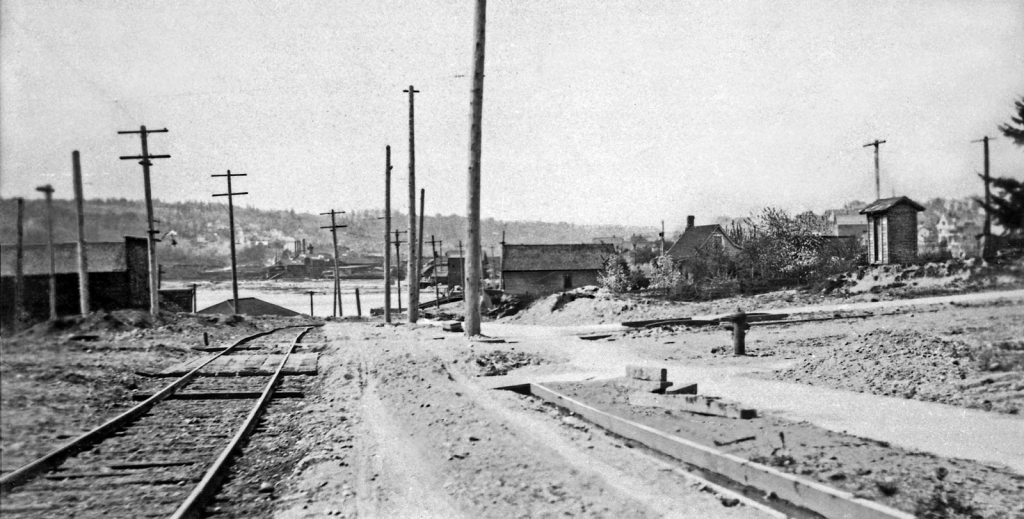

An image of newly-constructed trolley tracks in 1907 from what is likely now North 34th Street, looking toward Fremont. Historic Wallingford hopes to capture the look and feel of this era. (Credit: Seattle Municipal Archives)

The current price and scarcity of homes is historic, the need for urban development to prevent climate meltdown is historic, and the policy-driven exclusion of people of color from homeownership has been — and continues to be — historic. To their credit, Historic Wallingford is explicit in its application about both the exclusionary policies and their impact. But why they fail to consider their own historic districting as a new mechanism for exclusion is an oversight that I cannot understand.

Wallingford began as a rapidly-developed, affordable neighborhood built around accessible public transit as a response to a population boom. Why is it that we prioritize the preservation of the architectural vestiges from that period over its origins of growth and density in response to a need? How would this preservation effort address the reality that so many untouched structures remain due to exclusionary policy links in a chain since the ‘period of significance’?

Seattle homeownership is stratifying by race, which is the inevitable outcome from decades of restrictive zoning, and other exclusionary practices. These have led to lopsided access to economic opportunity. To protect only the architectural facades fails to acknowledge the high cost and the oppression undertaken to turn the neighborhood into Pleasantville for some, but off limits for others. More disturbingly, it serves to temper and strengthen the next link in the exclusionary chain of policies that have formed into single-family zoning.

As a homeowner in Wallingford, indeed of a home “contributing” to the period of significance in the initial feasibility study for the proposed Wallingford-Meridian Streetcar Historic District, I have enjoyed learning about the history of my home’s development and in the century since. You might rightly guess that most modern economic systems tend to benefit me and a historic district would be no different. The value of my home would be likely to increase even more than its already astronomic trajectory if it were adjacent to a historic district, and the impacts of construction and development of the housing our city desperately needs would continue to be felt in someone else’s backyard.

In fact, while the proposed Wallingford-Meridian Streetcar Historic District would not directly prevent the demolition of existing structures or limit changes to zoning, it would provide tax benefits for homeowners who want to renovate their homes (pending design review, of course). And that, my friend, is wrong. When we talk about systems perpetuating unearned privileges, this is precisely the type of policy to which we refer.

Setting the bar so low for historic designation and preserving an entire neighborhood of single-family homes is a slippery slope. Historic Wallingford is following in the footsteps of Ravenna-Cowen Historic District, which successfully designated 443 single family homes as ‘”historic” and avoided upzones despite being near the newly-opened Roosevelt light rail station, a multi-billion-dollar investment raising property values in the area. I also can’t help but notice that the so-called distinctive and historic architectural characters of these two districts are nearly identical with their 1900-1930s Craftsman, Tudor revival, Colonial revival, and Classical revival homes.

I love that the Good Shepherd Center, a Wallingford landmarked success, provides affordable space for organizations like the Tilth Alliance that benefit the community. There is certainly value in protecting unique and important structures, but protecting huge swaths of privately-owned single-family land doesn’t seem like a sincere use of the historic protection intent. If there are select homes that deserve some special consideration, so be it. But freezing 1,000 single family homes in amber would enshrine our mistakes rather than forge our future.

So what now?

After fostering an awareness and appreciation of the history of Wallingford, I believe more than ever that its foundational, cultural values would be best preserved through dense, affordable housing and public transit. I want coffee shops and local storefronts that I can walk to without competing with the frantic noise of 45th Street. I’d like to comfortably cross 50th Street, a thoroughfare that would see enforcement of its 25 mph speed limit only in my wildest dreams. I want more places to gather and play with friends and strangers.

People in Wallingford don’t really walk anywhere, we walk loops right back to our homes. I want more places to be in Wallingford. Although change is certainly complex and challenging, more housing would welcome new neighbors and allow us to consider new places for socializing and community building.

If the pending proposal is approved, my family’s former craftsman-gone-parking lot may become 330 homes in a 32-story tower with public greenspace. This development could provide more people with opportunities like my relatives had to pursue studies and launch careers in the opportunity-rich and light rail accessible U District. And that feels right.

To learn more about the tax implications of historic districts please attend the upcoming educational event on March 15, 2022 at 7pm with King County Assessor John Wilson & Chief Appraiser Jim Hall hosted by Share The Cities Community Education. Register here. Volunteers from that organization will be knocking on doors and talking to neighbors throughout March. They will also host an information table by Wallingford QFC with free notary services on Saturday, March 5 from 10am-12pm. Visit their website to learn more or get involved.

Molly Blank (Guest Contributor)

Molly Blank is a scientist, fourth generation Seattle resident, and University of Washington alumna as both a student and faculty member. A long-time tinkerer and maker, Molly appreciates the difficulty, creativity, and persistence required to envision a better future for ourselves, our neighbors, and the environments we belong to.